I remember when I was at school video in the classroom normally meant that it was the end of term and the big TV was being wheeled in to keep us quiet for an hour or two while we watched Blackadder and pretended we were doing so for its ‘historical accuracy’. The only real use of video for educational purposes I remember was the BBC series that a dedicated teacher must have videoed at 3am. Video facilities were far less advanced than those we have today. With access to the internet and a projector in every classroom, it’s now much easier to find anything we want.

I’ve always been a fan of using video with , mainly to provide a variety of authentic input materials, but video is also real in that it is multi-modal. Even when teaching in France, where we had two portable projectors between 15 teaching staff, unreliable electricity in the 15-year-old ‘temporary’ port-a-cabin classrooms and classes of up to 40, I found a way to use video. Video is a great resource when you have an almost monolingual class. Sure they might be able to understand you the teacher, but they need exposure to real English that isn’t automatically graded or of your own variety of English. My favourite video-based lesson was one I made for students at the Political Studies Institute around Nick Clegg’s tuition fee apology. That 2’30 video could be exploited in so many ways – and not just by me, by satirists, journalists, bloggers, politicians – it truly was a gift. I used it

- without the sound – what’s going on?

- for meaning

- for interpretation of events prior to the apology

- language focus – correcting a transcript (colloquial vs formal language)

- reaction to it/discussion about it

(The video had also been subtitled as ‘honest’ and turned into a song that was later sold on iTunes, both of which I used in class).

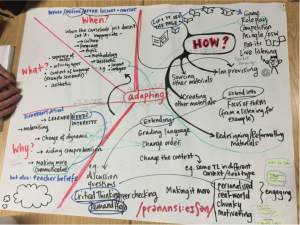

The session was really interesting seeing all of the different ways others had come up with to exploit video in the classroom, here are a few of my favourites

- guess what happened next

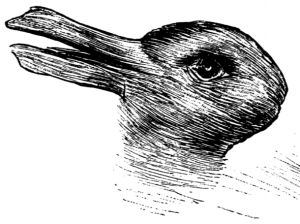

- guess what just happened – facial expressions and emotion

- how to… – for process descriptions

- story-boarding – narrative tenses

- video-telling (Jamie Keddie)

- narrating or putting a voice to a silent film (I love the BBC Walk on the Wild Side videos for this).

It’s amazing what can be done with video, and the free, easy-to-use software out there makes it accessible to most teachers. For this session though, I looked at augmented reality in the classroom and using student-created videos.

AR and student-created videos

Recently we’ve been doing formative exams including poster presentations by the students that were videoed for our records. We like to use them in class to that students can recognise how they can improve ahead of their finals. One area for improvement for most students was the interaction between their poster and their presentation: for many there seemed to be a large disconnect. In Paul Driver’s workshop we saw how augmented reality was used to embed video in posters around the college. This was my inspiration for this project. Using Aurasma Studio, I set up the students’ videos to pop up when they held their Aurasma phone app over their poster. This created a clear connection between their poster and what they were saying.

Working in pairs or groups of three, the students assessed how effective their posters were in supporting the audience through their presentation, and then other elements such as clarity and development of their arguments, use of sources etc.

The students seemed to appreciate the use of their videos through the app. Since their poster acted as the trigger for the video, they were able to take them away with them. It was much easier (once I’d figured out how to shrink a video file size – super easy when you know how) than emailing each student separately and allowed more movement and interaction in what would have otherwise been a very still, individual, screen-focussed task.

The use here was quite simple but I think it can be developed into something much more interesting and useful. What excites me about the project here is the possibility to give students something that their poster presentations hadn’t had previously: a real, wider audience (not just the teacher for the purpose of assessment) and longevity. Previously, at the end of term, weeks of work in the form of posters and videos were rolled up and filed away, but with AR the project could live on in the form on a mini-exhibition.

It also brings in the idea of digital literacy and how we can encourage our students to engage responsibly with technology and to build skills that may be useful in a world where communication is increasingly technology-based.

Edit: I’m currently working on a project when Aurasma is used to apply the principles of process-writing to presentations (process presenting?). I’ll write a post on it once it’s advanced a little further.