For last week’s seminar we all had to read up on the development of frameworks for materials evaluation. In groups we then had to create our own framework that we could see ourselves using when faced with the task of evaluating a textbook (or other ELT materials). Some groups furthermore had to apply their framework to the evaluation of one particular textbook. These groups then presented their frameworks and the findings of their evaluation in class.

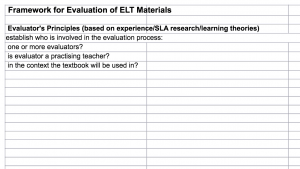

The group I worked in did not have to apply their framework to the textbook. What follows therefore is our idea of a general framework which we arrived at after reading a number of articles on the subject and which I adapted after seeing the other groups’ presentations (Framework for Evaluation of ELT Materials):

Whilst I agree with authors like Ellis (in Tomlinson, 2011: 214) who argues that materials are most effectively evaluated ‘in action’, the reality probably is that most evaluations happen pre-publication initiated by publishers who are interested in the opinions of teaching professionals regarding a new product and maybe some limited ‘test-driving’ of that product. The framework we devised is therefore to be used in a situation where one evaluator or a small group of evaluators test the value of a new coursebook in a teaching context he/she/they are familiar with. If evaluators do not work alone but collaborate on an evaluation, I think it is essential that they work within the same context in order for the evaluation to be most effective.

Evaluator’s Principles

Evaluator’s Principles

The first step in the evaluation process, in my opinion, should be to establish the evaluator’s/evaluators’ principles. When we talked about and established our principles during our first seminar we realised that there were many that we shared, some that were particularly valuable to us personally, some derived from current trends in SLA pedagogy and some based on our beliefs about learning in general. In any case, our principles have to be known to us and those who choose us to do an evaluation, as they will colour our opinions and analysis of the material. Once principles are established they can be compiled in a list of criteria against which the materials are checked to find out to what degree the materials meet these criteria (e.g. in a questionnaire using the Likert Scale).

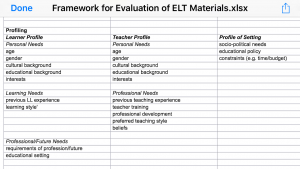

Profiling

Profiling

The second step involves the profiling of the group of learners the materials are aimed at, of the teachers who will be teaching with the materials and of the setting in which the teaching is to take place. In combination the different profiles describe the proposed context of use. I agree with Masuhara who suggests that often the analysis of teacher’s wants and needs gets ignored beside the analysis of learner needs (in Tomlinson, 2011: 236-266). Masuhara holds that both are equally important, if one is to provide teachers with materials that are truly useful to them and consequently effective for teaching. As in the first step profiling should result in criteria that can then be tested against the materials.

Materials Analysis

Materials Analysis

The third step should look at the material itself. I like Littlejohn’s idea of analysis involving various stages going from ‘objective description’ through to ‘subjective analysis’ and finally to ‘subjective inference’ (in Tomlinson 2011: 185). It is true that at the first level it is possible to be quite objective as you describe the overall appearance of the material, the layout and staging of content, publishing details etc. As it is impossible to analyse a whole book in minute detail the selection of parts of the textbook that are worthy of closer inspection becomes more subjective. However, what follows, i.e. a step-by-step description of exactly what happens in a task is then objective again, i.e. still an analysis. I think it is useful, as Littlejohn suggests, to see ‘task’ at this point to mean simply ‘what we give students to do in the classroom’ (Littlejohn quoting Johnson 2003: 5 in Tomlinson, 2011: 188). A more TBLT (Task Based Language Teaching) definition already presumes a specific interpretation of ‘task’ which is not applicable to all tasks and therefore cannot be applied in the evaluation of textbooks that are not informed by TBLT. The last level of analysis is more subjective than the second as it moves away from simply describing what’s there to the drawing of ‘some general conclusions about the apparent underlying principles of the materials’ (Littlejohn in Tomlinson, 2011: 197), e.g. by looking at who does what with whom the evaluator can guess at the roles that teachers and learners are expected to take on during an activity.

Evaluation

Once steps one to three have been completed the evaluator can look at all of the criteria together combined with his/her findings from the analysis of the material itself. This would be the actual evaluation stage. For example, the evaluator might have decided that learner-centredness and collaboration are amongst his/her valued criteria. The profiling shows that the teacher is happy in principle to hand over control to his/her students from time to time and confident about classroom management in such situations. The profiling also shows that students have experience of and are comfortable with working in a team. The analysis of the material finds that several tasks include group work activities. Overall it would then seem that the material is suited to the context as well as the pedagogical aims. As suggested earlier it would be most useful if these claims could then be tested by using the material with real students (preferably different classes in the same institution taught by different teachers) over a period of time.

References

Tomlinson, B (2011) ‘Introduction: principles and procedures in materials development’ in Tomlinson, B (ed) Materials Development in Language Teaching (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Littlejohn, A (2011) ‘The analysis of language teaching materials: inside the Trojan Horse’ in Tomlinson, B (ed) Materials Development in Language Teaching (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Masuhara, H (2011) ‘What do teachers really want from coursebooks?’ in Tomlinson, B (ed) Materials Development in Language Teaching (2nd edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press