What is Display Advertising?

Display advertising is described by Miller, M. (2010) as “banner ads in all forms”, including video format, standard banners, brand awareness banners, interstitial banners and interactive expandables. Each can be used to promote different messages from multiple touch points along the consumer journey. But the evolution from when the ad space was just bought and sold between advertisers and publishers has been huge. Technology has completely digitised the business into a much more efficient purchasing process.

The ad exchange was created to give an opportunity for advertisers to buy and sell specific audiences rather than unspecific packaged impressions by the thousands (which the ad network previously offered, Shiffman, D. 2008). Sellers would make their audiences available on their platform; buyers would then pick their audiences and then bid on them. As technology improved and this method of ad purchasing became more apparent, both buy and sell sides realised that they could make the process more efficient. The below graphic shows how the industry is now set up in layman terms:

A problem arose when it came to companies competing in these real time bidding auctions. Some firms didn’t have the technology or knowledge to carry out these transactions. It was vital that ad space was being bought correctly and on sites that wouldn’t damage the brand. To manage this process, Demand Side Platforms (DSPs) were created, where constant optimisations used data to create more efficient purchasing decisions for the advertisers (Busch, O. 2014). Of course the publishers had the same technological and knowledge limitations so Sell Side Platforms (SSPs) were created to optimise the selling points for these different publishers.

So now we go onto look at how programmatic buying has changed the way media is purchased through the ad exchange.

What is programmatic buying?

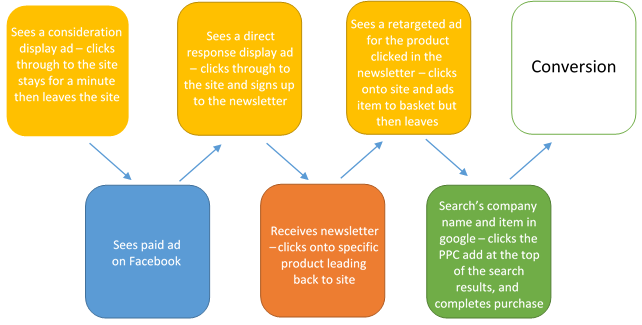

Put simply, programmatic buying is the use of automated technology to faster and more efficiently trade digital media (Smith, M. 2014). Real time bidding (RTB) was just the start of programmatic buying. It has now evolved into much more than purely auctions on the Ad Exchange, with advertisers and agencies now being able to use programmatic techniques to transact, not only unreserved inventory, but reserved inventory as well (Busch, O. 2014). Programmatic meant that marketers could bid to show a different add to a different user based on data collected about that user. This data is collected from cookies that are placed in the text information when data from a web page is downloaded to the users computer when they click on the site. Improving this data pool to refine the programmatic process has made it the ideal tool for online marketing, giving advertisers the ability to serve the right ads to the right people at the right time, what all marketing should strive for. On top of this audience segmentation targeting, it has allowed digital marketers to set budgeting parameters like what they are willing to pay for an impression, creating another efficiency this time in monetary value.

Programmatic has had a huge growth rate by a 70-80% uptake as marketers begin to embrace new formats for online display (Yuan, S. et al, 2013). Once there are more engaging formats to choose from, there becomes more opportunity for the industry to become smarter about their marketing and develop a consumer journey through display. From a branding perspective this higher impact inventory hasn’t been there until recently, until these ad formats came along there’s been more of a direct response focus using standard units which are not very engaging. However, mixing these branding formats with RTB is where a problem starts to creep in.

What issue does programmatic buying create?

The technology and data that is the backbone of programmatic tends to be obsessed over too much, losing focus on what is really going to drive click through rates and engagement from the user (Busch, O. 2014). Ads can become subject to lacking creative ideas as firms can lose focus on attracting the customer.

Programmatic has been more frequently used at the end of a consumers journey because it’s where measurement is more accurate; but with the development in accuracy shown in the blog about attribution modelling, return on investment can be measured more efficiently higher up the consumer journey. This creates a challenge for creative agencies as programmatic reaches into the brand space, it is going to deeply affect the way they develop ideas and profoundly affect the assets they produced. The granularity of targeting that programmatic allows means that there is an increasing quantity of assets that needs to be created to benefit from this targeting. The difficulty for creative agencies is developing these assets to the same quality but just in larger quantities to really maximise the opportunities that this kind of audience targeting generates.

To conclude…

Has programmatic buying and real time bidding brought about the end of creativity? It depends on the creative strategy implemented. Media agencies have to work more closely with creative agencies and these creative agencies have to become more agile. If a brand wants a creative unit turned around in 24 hours, it has to become possible to turn it round in this time without losing quality. Creative quality is key. After all, what’s the point of having the right ad in front of the right person; at the right time when the ad looks so bad it doesn’t drive engagement

For further information, you may find the following of interest:

Define It – What Is Programmatic Buying?

A super accessible beginner’s guide to programmatic buying and RTB

10 Things You Need to Know Now About Programmatic Buying

References

Busch, O (2014). Programmatic Advertising: The Successful Transformation to Automated, Data-Driven Marketing in Real-Time. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. p75.

Miller, M. (2010). Display Advertising. In: The Ultimate Web Marketing Guide. USA: Pearson Education.

Shiffman, D (2008). The Age of Engage: Reinventing Marketing for Today’s Connected, Collaborative, and Hyperinteractive Culture. California: Hunt Street Press. p177.

Smith, M (2014). Targeted: How Technology is Revolutionizing Advertising and the Way Companies Reach Consumers. New York: American Management Association.

Yuan, S. Et al. (2013). Real-time bidding for online advertising: measurement and analysis. Data Mining for Online Advertising. 13 (3)