Targeted advertising is very useful from a business standpoint since it helps a company reach potential customers who (appear to) fall very much within its presumptive market segment (Farahat and Bailey, 2012). However, a balance needs to be struck between over generalisation and over personalisation. If the ad content is too personal it may be perceived as ‘creepy’, carrying with it a risk of ‘freaking out’ consumers; if its focus is too specific it runs the risk of its appeal being too narrow and thereby capturing only a limited proportion of the intended target demographic; too broad and the ad may be ignored altogether, or its impact diluted, with the product being pitched to a largely indifferent consumer populace. Personalising ads is therefore clearly a key element of targeted advertising, yet is fraught with problems.

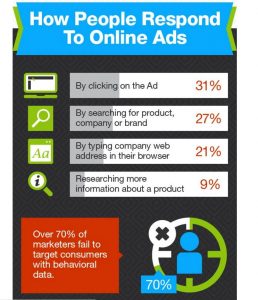

Info-graphic demonstrating effectiveness of targeted advertising

Found at: http://www.callcredit.co.uk/media/1218294/targeted-display-advertising.jpg

Some ways advertisements are personalised

Before exploring the problems that can arise from personalisation in targeted advertising, it is important to briefly establish some of the channels in which targeted advertising can be utilised.

Targeting generally looks at behaviours, audience, time, and demographics in order to attract the consumers the ad is aimed at. Personalisation is useful to ensure that the ad is relevant to the user who sees it. This is achieved based on information given by the user to a company, information collected or inferred with ‘tags’, or found with data from a third-party (Davis, 2014 – provides a more extensive list of channels and types of targeted advertising).

Info-graphic on the effectiveness of re-targeting Found at: http://corp.wishpond.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/7-incredible-retargeting-stats.png

- Retargeting – the primary channel for personalised advertising. This is when a company tracks the browsing history on their website (and can extend to emails) using cookies to base advertisements on. To avoid the risk of being creepy, companies often detail the use of cookies when users visit (although, Cranshaw, 2012 et.al suggest that Online Behavioural Advertising (OBA) disclosures need to be communicated clearly or they may go unnoticed). See Moth, 2014 to ensure retargeting isn’t intrusive.

- Real-time bidding – a less personal form of retargeting that can be used to target more generic audiences i.e by demographic or geography and thus can be used to tailor an ad to a region by targeting IP addresses.

- Social media advertising – popular social media sites such as Facebook have a lot of information on their users, thus they can utilise this information such as information users have inputted, interactions with others, pages they browse etc.

The problem

Because consumers have become more aware of targeted ads becoming increasingly personalised, concerns have been raised by a large majority that their privacy is at risk, rather than the concerns centring on whether ads are relevant to them.

An online survey conducted by CloudSense found that 51% do not want more personalised ads. In another survey conducted by Razorfish Global Research, 77% of respondents believed their privacy was being invaded by targeted advertising. The fact that a simple Google search on the creepiness of targeted advertising produces many results, as well as guides on avoiding targeted ads altogether, indicates that this is a large problem widely felt throughout the web. However, this may not just be a case of ads being too personal, it may just be a result of poor implementation, as suggested by Calvert, 2015.

Balancing personalisation and privacy

The matter of whether a balance between personalisation and privacy can be achieved has been the subject of considerable academic examination.

There are many academic articles which engage in debating the challenges arising from balancing OBA and privacy when using targeted advertising. Some offer suggestions or models on how to avoid perceived ‘creepiness’. For example, Toubiana et. al, 2011 suggest a targeted advertising system that aims to preserve privacy, while Haddadi et. al, 2011 present a model to address mobile advertising privacy concerns. On the other hand, Johnson, 2013 suggests how consumers could avoid targeted or personalised advertisements because of the privacy infringement, emphasising the importance of striking a balance between personalisation and privacy. In avoiding privacy infringements, Martin et. al, 2016 state that studies suggest transparency in data management practices can help to negate feelings of mistrust and violation caused by ‘creepiness’.

Many of the models given are complex and difficult to follow and thus there is no simple answer to balancing these two elements. However, there are some basic guidelines that can be followed.

How to properly use personalisation in targeted advertisements

- Ask for permission – as suggested by Martin et. al, transparency by asking permission to track user information may help to reduce negative feelings. Be clear about the data being collected.

- Don’t over-personalise – this may seem obvious, but as an example of this, the company Target predicted that some female customers were pregnant and also predicted when the baby was due by tracking purchasing patterns and targeted adverts accordingly. This is an extreme example; a practice that should be avoided at all costs. To ameliorate this obvious creepiness, they broadened their advertisements to not just include baby-related products.

- Use less data – though sounding counter-intuitive, using less data when personalising may be effective in avoiding creepiness. Some personalisation can go a long way, but use of too much detail, such as the above example, may have the opposite effect.

- Focus on information that people are fine sharing – Information such as facts like occupation, gender, City they live in are some examples that people may be fine with sharing and thus are more appropriate to use when thinking about personalised targeted advertising. But do bear in mind that privacy limits are subjective.

References

Calvert, G. (2015). Personalised ads are here to stay but brands must beware ‘freaking out’ consumers. [online] Campaignlive.co.uk. Available at: http://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/personalised-ads-stay-brands-beware-freaking-out-consumers/1347792 [Accessed 4 May 2017].

Davis, B. (2014). A guide to personalised advertising online. [online] Econsultancy. Available at: https://econsultancy.com/blog/64859-a-guide-to-personalised-advertising-online/ [Accessed 4 May 2017].

DeAngelis, S. (2015). Targeted Marketing: Helpful or Creepy? – Enterra Solutions. [online] Enterra Solutions. Available at: http://www.enterrasolutions.com/2015/04/targeted-marketing-helpful-creepy.html [Accessed 4 May 2017].

Dooley, R. (2012). Three Ways to Avoid Creepiness. [online] Futurelab. Available at: http://www.futurelab.net/blog/2012/02/three-ways-avoid-creepiness [Accessed 4 May 2017].

Farahat, A. and Bailey, M. (2012). How effective is targeted advertising?. Proceedings of the 21st international conference on World Wide Web – WWW ’12.

Faull, J. (2014). 51% of people don’t want personalised ads. [online] The Drum. Available at: http://www.thedrum.com/news/2014/06/06/51-people-don-t-want-personalised-ads [Accessed 4 May 2017].

Haddadi, H., Hui, P., Henderson, T. and Brown, I. (2011). Targeted Advertising on the Handset: Privacy and Security Challenges found in Müller, J., Alt, F. and Michelis, D. (2011). Pervasive advertising. 1st ed. London: Springer, pp.119-137.

Johnson, J. (2013). Targeted advertising and advertising avoidance. The RAND Journal of Economics, 44(1), pp.128-144.

Leon, P., Cranshaw, J., Cranor, L., Graves, J., Hastak, M., Ur, B. and Guzi, X. (2012). What Do Online Behavioral Advertising Disclosures Communicate to Users? Technical Reports: CMU-CyLab-12-008.

Martin, K., Borah, A. and Palmatier, R. (2017). Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance. Journal of Marketing, 81(1), pp.36-58.

Moth, D. (2014). Retargeting: how to ensure it is useful rather than intrusive. [online] Econsultancy. Available at: https://econsultancy.com/blog/64206-retargeting-how-to-ensure-it-is-useful-rather-than-intrusive [Accessed 5 May 2017].

Rajeck, J. (2016). Four ways to avoid ‘creepy’ personalisation. [online] Econsultancy. Available at: https://econsultancy.com/blog/68303-four-ways-to-avoid-creepy-personalisation/ [Accessed 4 May 2017].

V. Toubiana, A. Narayanan, D. Boneh, H. Nissenbaum, and S. Barocas. (2010). Adnostic: Privacy preserving targeted advertising. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS ’10.