by Aidan McGarry

In January 2017, as the inauguration of Donald Trump neared, New York-based artist, Morgan O’Hara felt the need to protest. As a concerned artist, she had marched many times, but this moment seemed to call for something else. She wanted stay clear of the campaign’s toxic excesses, and take action silently. On Jan. 5 she woke up with the idea of copying the U.S. Constitution by hand. While she often hand-copies texts as part of her art practice, she hadn’t thought much about the Constitution before. She only knew she wanted to do it, and to do it with others in a public space. On Inauguration Day she went to the New York Public Library with a small suitcase of pens, a few Sharpies, papers and copies of the Constitution. She brought old notebooks, half-used drawing pads and loose sheets to share with anyone who might show up. She began writing.

To date she has organised 43 sessions. ‘Handwriting the Constitution’ has been taken up in many states in the United States, as well as in Italy, Germany, and Portugal. Plans for next year include sessions in Ireland, Israel and Japan. In each case, people handwrite their chosen documents written to protect human rights.

Morgan O’Hara is an artist. Her work can be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in Washington, the British Museum and elsewhere. Aidan McGarry spoke with her about the ‘Handwriting the Constitution’ project, protest, and politics.

AMG: You describe your project ‘Handwriting the Constitution’ as the introvert’s protest? What does this mean to you?

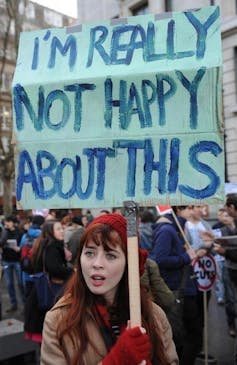

MOH: Well, it is an example of protesting which is silent and pretty much immobile, as opposed to the kinds of protests which were happening at the time of Trump’s inauguration, or have traditionally been done where people go out and march, chant slogans, or yell or wave banners. All of those are quite extrovert activities which I have done in the past, but this situation got me to thinking about what an introvert could do. I thought this action had to be something quiet, something silent, but active. I don’t know exactly where the idea came from but I woke up one day and it was in my head to handwrite the constitution and it made me smile because an introvert can write something, can read something and it can still be an act of protest. I soon realised I had to do it in a public place so I decided to do it at New York Public Library in a quiet room. I think it would have been performative whether I had done it with other people or not, just because it was an action I was doing and it had its own parameters. A friend of mine asked if she could publicise it on Facebook and initially I wasn’t sure as I was concerned that it might change the quality or it could be distracting but I decided to embrace it. So I prepared extra materials in case more people turned up. At the first session, I was writing for an hour on my own, then two people I know turned up and then seven people I hadn’t met before arrived. We were soon all handwriting the constitution together.

Do you think there is a performative quality to the writing or what purpose does the action of writing serve?

The action is very important. Writing is very different from reading and typing. When you write something out it somehow gets into your head and your body in a more profound way. I think drawing serves the same function. I don’t own handwriting and I don’t own the constitution. I just happened to put them together at a key moment. The combination of the two is very powerful. It’s definitely performative even when I am there alone because when I there I feel visible as I am the only one writing. In addition, it is my intention to do this publicly as a performance. It is a private action consciously made public.

Is it just the US constitution?

No. I am interested in handwriting any documents which have been written in defence of human rights. I have written out the UN Declaration of Human Rights in Taiwan when I was working there. It didn’t make sense to write the US Constitution in that situation. Some of the participants in Taiwan chose to handwrite the Declaration alternating paragraphs in both Chinese and English.

In the testimonies of the participants I read they talk about how handwriting the constitution anchors them. How is this possible?

I’m not sure how this works, but it definitely does. It has a calming effect. It’s like reminding yourself that rights exist and that you have rights at a time when everything else is falling apart. It is the grounding; this is the earth on which we stand, the fact that we have these rights and they have been defended time and again through all these different documents. And when you are in time of crisis, these documents remind you that you have a right to live in peace, to live unmolested, to live in harmony.

I am surprised that people immediately think it is art. I have not mentioned this when describing the project. I am an artist, so I suppose people think it is art. Actually, I don’t care what it is called as long as we do it.

I think that is what is so interesting about this project. I think many people think of rights as an abstract ideal but all laws come alive when you invoke them or they are violated. So they are dead letters on a page but there is something in this project when you write them out, they are being invoked, they are made to be alive, they are not just abstract words arranged on a document. Their meaning is much more significant. Do you think that the project is political?

Yes. I have never identified myself as a political activist and I am surprised by the discussions I get into because of this. I have to learn a lot because people ask me questions about history and the documents. For me it has becomes an intellectual and conscious and creative process.

It would be interesting to see this project manifest in different places. There are places where rights are under attack like in Hungary, Turkey, Russia, Poland, and increasingly in the USA. And there are places where the squeezing of rights is more latent. That’s why it is interesting this is happening in Germany and Italy, as we think of Germany as a stable democracy but rights are constantly being squeezed and ignored. So it is good to have this, as a reminder of what you have and what you have a right to.

There’s a wonderful word in Italian when you have had enough of something, you say ‘Basta!’ which is exactly as it sounds. Enough! I take this idea-word-feeling to indicate that we have had enough with these encroachments on our rights. There has been so much in US politics which has been uncivilized and crude, not to mention illegal, and many worse things are happening in many places around the world. Collectively we need to remind ourselves of our dignity and our rights and insist that they be respected. So, yes, Handwriting the Constitution is political, yes, it’s introspective and yes, it’s performative. All three. It is also a silent action which has the potential to be transformative. I hope that in 2018 and beyond more and more people will participate and will feel empowered through this simple action.