Once a teacher has established and articulated the principles providing the roots of the materials, it is important that the author creates a framework to support the different stages of development. This, in theory, is sequence of steps and stages that allows the author(s) to evaluate and adapt the materials in-line with the aforementioned principles.

This is exemplified by the diagram below in Jolly & Bolithio’s chapter cited in Tomlinson (2009).

This shows that to identify a need is the starting point from which all things follow. This is a logical starting point and something that I must make sure I apply to my own materials. The concern I have is that I might be distracted by novelty and pleasing aesthetics rather than the pedagogical need of my learners. One of the main principles from my last post was engagement; there may have been occasions where my inclination has been to prioritise engagement and cosmetic motivation, while not asking myself “what will my students take from this?” Is being engaged enough? Was I pandering to the students’ approval? If the activity is involving and it encourages receptive and productive use of English then its merits as a pedagogical task cannot be questioned.

In my day-to-day interaction with materials, it is normally the case that I adapt something from published or shared peer materials. This in turn means that upon discovering a task, or a suitable piece of input, it might be the pedagogy or the context that draws my attention and I would work backwards from there. It is rare that I will have the time to carefully consider each one of the steps in the diagram and create my own materials. However, whatever I create or adapt needs to be part of the overall curriculum. It needs to recognised that individual materials are micro-considerations in the grand scale of a course. The macro-perspective is the desired aim of the students e.g. coursework or tests.

“Material writing is regarded as an end in itself, teachers believe that they can just write materials and not teach. The writing process is pointless without constant reference to the classroom.” Jolly and Bolitho (2009)

A critique of the diagram above is that it is a sequential and a rather undynamic illustration of what it takes to produce good materials. Jolly and Bolitho (2009) admit that this particular diagram is a simplified version of the ‘real’ process. The chronological simplicity may work for some or on occasion, but in reality it does not mirror the complexity that learning and teaching demands in the adaption and fine-tuning for the various context and needs materials could be used for.

This diagram can be considered as more dynamic and self-adjusting in its approach to the process. The idea of flexibility appears to run through the core of material design and a framework should reflect that. In addition, Jolly and Bolitho (2009) point out “the human mind rarely works in a linear fashion when attempting to solve problems”. A flexible framework visualises a variety of optional pathways or feedback loops, which make the process dynamic and self-regulating. Doing an evaluation after classroom use means authors can check if they have met their objectives. Failure to meet objectives could be attributed to any or all of the preceding phases.

There are other factors that may affect outcomes when evaluating the success of materials that are outside of the framework, such as classroom management. In fact some form of analysis and/or pre-evaluation should take place at every stage of the process in order to allow the original principles articulated by the writers at the start to inform adjustments.

Pardo and Téllez (2009) use Graves’ (1997) non-sequential framework, which looks at the essential components in the process of creating and adapting didactic learning materials.

Graves’ diagram is an interesting framework because it is not one of equal or sequential parts but rather one in which each individual’s context determines the process that needs more time and attention. It shows the seven essential components that make up the framework:

- Needs assessment

- Setting goals and objectives

- Content

- Developing and selecting materials and activities

- Organisation of content

- Evaluation

- Resources and constraints

The telling aspect of this diagram is that it still has setting assessment needs at its core. It is clear that materials development (in the view of the experts) is at its most effective when it is tuned to the needs of a particular group of learners. Therefore the people who understand their learners are those who should be responsible for the principles and frameworks that are used to develop the materials used in their classrooms. All teachers who want to create and adapt materials that match their own principles need a grounded understanding of material frameworks. Knowledge of frameworks will assist in the evaluation of other people’s materials.

Materials writing raise some of the issues important to learning:

- Selection and grading of language

- Awareness of language

- Knowledge of learning theories

- Socio-cultural appropriacy

All teachers who endeavour to author their own materials will in fact start to learn their best methods and start to teach themselves. The process of trialling and evaluating are vital to the success of any materials (Tomlinson 2011)

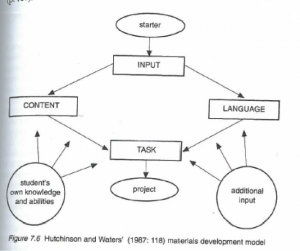

This extended model for designing materials provides a coherent framework for the integration of various aspects of learning while at the same time allowing enough room for creativity and variety to flourish.

Hitchison and Waters (1987), as cited in Tomlinson (2011)

- Input may take the form of a text dialogue, video-recording diagram etc.

It provides:

- Stimulus to activities

- New language items

- Models of language use

- Topic for communication

- Opportunities for learners to use information-processing skills

- Opportunities for learners to use existing knowledge both of the language and the subject matter.

- Content: texts convey information and feelings; non-linguistic input, and can be exploited to generate meaningful communication.

- Language: learners need language to carry out communicative tasks and activities. Good materials allow learners the opportunities to analyse language of the input, study how it works, and then practise putting it back together again.

- Task: since the ultimate purpose of language learning is language use, materials should be designed to lead to toward a communicative task in which learners use the content and the language knowledge they have acquired in the previous stage. (Hitchison and Waters,1987)

There are limitations to this framework as it lacks analysis of the learner’s current knowledge. Also, there is an assumption that productive competence is the only aim of a language learner and as Harwood (2010) rightly points out, there are a great number of learners (outside English speaking countries) whose primary/study objective is reading knowledge/competence. Therefore there is no reason why the final/main task should not be a receptive one (listening and reading).

Having examined several framworks it becomes clear that they all have their pros and cons. The process of designing materials is perpetual cycle that is informed by so many factors. Flexibility and reflection, i.e. evaluation at all stages, seem to be the key terms when constructing a workable framework. I feel quite privilaged to work in an environment that encourages the sharing of materials and ideas amongst its peers. In general, there is a supportive dynamic and the feedback loop is always available for ideas to be discussed and developed. In addition, I feel confortable to ask my students for their thoughts and feelings toward materials, as well as analysising their actual output.

References

Harwood, N. (2010) English language teaching materials: theory and practice, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Pardo, A. N. & Téllez, T. (2009) ELT Materials: The Key to Fostering Effective Teaching and Learning Settings Materiales para la enseñanza del inglés: la clave para promover ambientes efectivos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Profile Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11, 171-186.

Tomlinson, B. (2011) Materials development in language teaching, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.