Decolonise Brighton University – the story so far

Naomi Salaman published in

University of Brighton Decolonising the curriculum Issue 2 December 2019 Moncrieffe

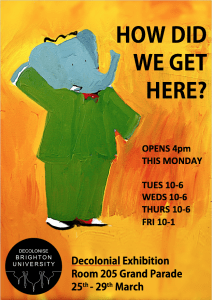

Last year Fine Art Critical Practice students organised decolonising activist Melz Owuzu to come to speak to students.[i] Decolonise Brighton University formed bringing together students from across the School of Art , ‘challenging the legacies of colonialism and racism on campus’. An open call was sent out for a Decolonial Exhibition of student art work, with the title How did we get here?

As students thinking about how to decolonise our curricular, asking ourselves ‘How did we get here?’ provokes the interrogation of narratives that have dominated education and shaped society…..’[ii]

exhibition poster image Virgile Demo

The poster for the exhibition was of a thickly painted, colourful rendition of Barbar the Elephant, in his familiar green suit and crown, very much the picture of the colonial subject as described by Fanon and others. Having learned something in the Western metropolis Barbar returns ready to rule, having interiorised colonial power and ways of doing things, ways of thinking. The painting of Barbar was made by a second year painting student, Virgile Demo. Decolonise Brighton University set up regular meetings across campus and came up with a suggestion for the start of the Autumn Term to spend the first two weeks in studio thinking about the question ‘why is my curriculum so white?’. That’s still a work in progress.

Decolonise Brighton University adopted an inverted graphic representation of the familiar domes of the Brighton Pavilion, as a logo, that you can see on the exhibition poster.[iii]The graphic was made by Laura Hargreaves, a sculpture student. This simple visual brings us to the heart of the paradox of the history and legacy of colonialism on our doorstep. The domes are architectural archetypes – images of otherness and colonial fantasy that are at the same time normalised as the everyday fabric of our city, our local museum and cultural heritage. As such they are ours and they are other. As one of the major attractions the domes also function as a sign for the city, used by the tourist trade as well as many organisations such as the local council and both Sussex and Brighton University.

The idea to turn the domes on their heads, makes the familiar strange and confronts us with our everyday reality in Brighton while offering a compelling example of the centrality of the image to the politics and workings of ideology. An inversion is literally how Marx describes consumer ideology, that we see things upside down, not as they really are. The image plays a crucial part in this process.

In the School of Art at Brighton University where I teach, all students are encouraged to play with images; to invent and to turn things around and see what happens. Only rarely does this activity find traction with the world in a political way. The students who set up Decolonise Brighton University began work on the taken-for-granted, every day, common sense visuality that forms the basis of ideology, the not-normally-questioned. Some of the Fine Art Critical Practice (FACP) students who set up the decolonise group went on to do related work for their degree show which took place in May/June in Grand Parade.

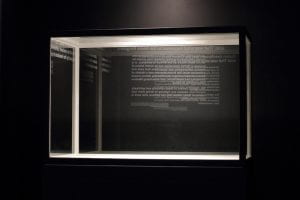

Liz Crane and Al Coffey were both founding members of Decolonise Brighton University. They worked with fellow FACP student Tom Nicholson to produce two final year art installations that investigated the legacy of the British Empire alongside the culture and politics of our national collections. They constructed LOST TREASURES– a dramatic darkened room with spot lights revealing strident wall texts about the removal of important cultural objects from their original location, referring in particular to the Elgin Marbles and the Benin Bronzes. In the dark room was a well-lit, empty glass display case.

Lost Treasures, empty vitrine

Liz Crane, Al Coffey, Tom Nicholson

Fine Art Critical Practice Graduate show 2019

‘Lost Treasures represented some of the arguments for the repatriation of stolen culture. Specifically, it highlighted the symbolic and political significance of absence for communities all over the world who are asking for the return of artefacts obtained by the British in a time of empire. The installation consisted of a minimalist black room, made to resemble a British Museum blockbuster exhibition. Spot lit quotes from artists, activists and scholars provided some context for the empty vitrine that dominated the room.

Throughout the installation, the focus was not on our own words but those of others who are on the frontlines, who can speak personally about how the loss of culture affects their identity. Amplifying marginalised voices was important to us, coming from a commitment to the decolonisation of museums and other cultural institutions such as universities, where whiteness dominates.’ [iv]

Another work from their degree show Symbols of Empire, involved installing 16 national flags up the main staircase at Grand Parade.

Symbols of Empire

Liz Crane, Al Coffey, Tom Nicholson

Fine Art Critical Practice Graduate show 2019

Symbols of Empire had a caption on the wall which read

These are the flags of the 14 British Overseas Territories under the jurisdiction and sovereignty of the UK. First flown together in Parliament Square in 2012, they are used to demonstrate the extent of Britain’s realm to visiting state officials. The animals, plants and ships depicted symbolise violent histories of conquest, slavery and environmental exploitation for Britain’s commercial and political gain, all under the Union Jack.

Over the last few decades many of Britain’s overseas territories and colonies, the remnants of a vast empire, have sought and won independence. The territories represented by these flags have either voted to remain under British rule or have been unable to exercise their democratic right. One of the most shocking cases is that of the British Indian Ocean Territory, where local islanders were illegally expelled by the British in the 1970’s to make way for a US military base. They have been campaigning for the right to return to their homes since.

The work of these students was ambitious in physical scale and in what they addressed. It was well received, and they achieved very high grades, even within the band of First Class Honours, and went on to win prizes. If I had the ear of Charles Saatchi I would suggest he install their exhibition next to his block buster Tutankhamun show, or maybe more to the point at the British Museum as an add-on to the Enlightenment Gallery. The 2019 graduates of Fine Art Critical Practice were a formidable group of artists and thinkers, and it was a privilege to work with them. Students in current years are likewise involved in these issues – and the Decolonise group is university wide. Follow the students’ lead and join Decolonise Brighton University.

end

[i]https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/facp/2019/01/30/melz-owusu-on-decolonising-the-curriculum/ See FACP blog post

[ii]From the exhibition press release and gallery wall text https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/facp/2019/03/25/student-pop-up-exhibition-decolonise-brighton/

[iii]https://www.facebook.com/decolonisebrighton/

[iv]Liz Crane in email to author, November 2019