An exploration of occupational therapists’ views and experiences of using evidence-based practice to develop professional knowledge in a local authority setting

Introduction:

Occupational therapists are expected to engage in evidence-based practice and to be aware of the importance of research as the foundation of the profession’s evidence base. This appears to be the first study that has explored local authority occupational therapists’ views and experiences of evidence-based practice and how they use it to develop professional knowledge.

Method:

A focus group data collection method was employed. Two focus groups, comprising seven occupational therapists each were conducted. Occupational therapists who participated in the study had been working in the local authority setting from between six months to thirty years.

Findings:

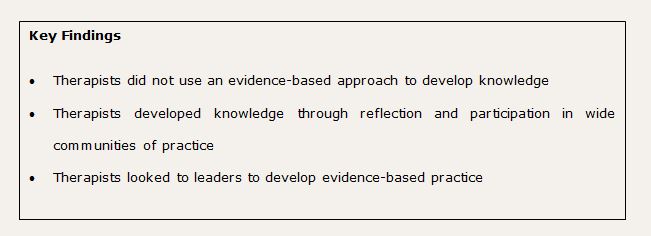

Occupational therapists did not draw on research evidence to build their knowledge. Therapists valued the evidence of the lived experience of clients, their own and other’s knowledge and experience, including the perceived evidence-based knowledge of health colleagues. Therapists developed their knowledge using these sources of evidence, through reflection and participation in wide communities of practice. Therapists looked to others to lead on developing evidence-based practice in the local setting.

Conclusion:

Occupational therapists did not use an evidence-based practice approach to develop professional knowledge. Peer learning and role modelling strategies may enable occupational therapists to become more evidence-based in order to enhance their practice and meet professional standards.

Introduction

The purpose of evidence-based practice is to provide effective care and improve client outcomes, to promote an attitude of inquiry in health professionals and ensure resources are used wisely (Hoffman et al 2010). Evidence-based practice has also been viewed as a matter of professional survival, set against a backdrop of rationing resources, consumerism and managerialism (Taylor 2007, Trinder, 2008). The high value placed on evidence-based practice by the occupational therapy profession, is reflected in the College of Occupational Therapists’ Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct (COT 2015), the College’s Standards of Practice (COT 2011) as well as the Health and Care Professions Council Standards of Proficiency for Occupational Therapists (HCPC 2015), all of which require occupational therapists to engage in evidence-based practice and to be aware of the importance of research as the basis of the profession’s evidence base.

A local authority consultation exercise, in the researcher’s practice setting, was undertaken with staff groups to ascertain the values that underpinned their day-to-day work. Consultation with a group of occupational therapists revealed the importance they placed on evidence-based practice to justify the profession and their interventions. The occupational therapy literature has highlighted the value placed on evidence-based practice by occupational therapists although in practice, it has proved difficult to implement, with studies focussed on the barriers to research utilisation primarily in health-based settings (Robertson et al., 2013; Upton et al., 2014). Few studies have investigated how occupational therapists use different evidence types, including research evidence to construct knowledge and it would appear, none have explored evidence-based practice from the perspective of occupational therapists working in a local authority. The aim of this study was to gain insights into occupational therapists’ views and experiences of evidence-based practice and how they use it to develop their professional knowledge in one local authority setting.

Literature Review

An early, often quoted definition of evidence-based practice, derived from evidence based medicine, is: ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al 1996 p.71). Brannigan (2007) described the evidence-based process as using the best evidence from research, balanced with clients’ values, clinical judgement and resource implications. Nevo and Slonim-Nevo (2011) objected to the prominent role of research in the evidence-based practice process and in particular, the hierarchy of evidence where systematic reviews and quantitative randomised controlled trials were valued to the detriment of experience and professional judgement. Nevo and Slonim-Nevo (2011 p.1193) used the term ‘evidence- informed practice’, to represent the use of a broader range of evidence to be used in a client-centred, flexible and intuitive way by practitioners to support the client’s changing needs and situation. Reagon et al (2008) developed the idea of ‘multiple truths’ (p.433) from a grounded theory study, where evidence-based occupational therapy involved the systematic consideration of information from multiple sources and applied in conjunction with the client within a client-centred, occupational therapy paradigm. However, Hoffman et al (2010) argued that the term ‘evidence’ in evidence-based practice served a specific purpose, which was to highlight the need to value and use information from research which was often underused.

A systematic review of published research on the subject of occupational therapists’ attitudes, knowledge and use of evidence-based practice was undertaken by Upton et al (2014). Thirty-two research papers, published between 2000 and 2012 were reviewed: twenty-three were quantitative, eight were qualitative and one was a mixed methods design, carried out in health-based settings in a number of countries, including the United Kingdom. The strengths and weaknesses of the studies were discussed with fourteen out of a total of thirty-two papers rated as good or strong quality. This review found that whilst occupational therapists held positive views of evidence-based practice, a number of barriers to its implementation were identified: lack of time and caseload pressures; the culture of the organisation; limited research appraisal skills; poor access to research and tensions with client-centred practice. In an action research study, Robertson et al (2013) found that the barriers to implementing evidence-based practice reflected the findings of earlier research papers reviewed by Upton et al (2014), prompting questions about how occupational therapists constructed their knowledge, using evidence, through critical reflection and participation in communities of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991).

The seminal theory of Schon (1987) proposed that professionals developed their knowledge in complex and challenging practice settings through a framework of reflection-in-action (thinking and acting in the moment), and reflection-on-action (analysing and interpreting the event after it has happened). Brookfield (2009) argued that a deeper level of critical reflection was required to examine and challenge the assumptions and power dynamics that framed everyday practice. A key element of critical reflection is being able to view situations and actions from multiple perspectives, including those from theory and research, to lead to informed actions and ‘an appreciation of the bigger picture of implications, surrounding the problem at hand’, (Jay and Johnson, 2002 p.79). In evidence-based practice, critical reflection can provide a framework for exploring and managing the power imbalances between the different evidence types (Petr and Walker 2009), and reconcile the tensions that exist between the technical rationality of research and occupational therapy practice (Blair and Robertson 2005).

Professional knowledge has been described as more than a store of cognitive knowledge, involving shared values, beliefs, ways of reasoning and tacit knowledge that are constructed through the interaction between professionals (Higgs et al 2004). This interaction can occur through a process of engagement in a community of practice (Lave & Wenger 1991), defined as: groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact on a regular basis (Wenger 2007 p.1). In relation to evidence-based practice, Gabbay and le May (2004 p.3) undertook an ethnographic study in primary care teams, and observed that general practitioners and nurses rarely consulted research evidence but relied on collectively constructed ‘mindlines’, informed by brief reading, their own and other’s professional experience, patients, organisational demands and developed through informal interactions in fluid communities of practice. The researchers acknowledged that their research had been conducted in well-functioning teams and that their ideas concerning ‘mindlines’ needed to be tested in different settings.

In summary, the debates in the literature concern what constitutes best evidence in health and social care practice, based primarily on the opinions of academics rather than empirical research and the views and experiences of practitioners and clients. The occupational therapy literature comprises of mostly quantitative studies focussed on the challenges to putting research into practice in health-based settings and it would appear that few studies have been conducted in local authority settings. It also appears that little attention has been given to understanding how occupational therapists develop evidence-based knowledge, through strategies such as reflection or participation in communities of practice. The apparent gaps in the literature helped to define the research question: An exploration of occupational therapists’ views and experiences of using evidence-based practice to develop professional knowledge in a local authority setting.

Method

A qualitative design, by means of focus group interviews, was applied to the research question. Qualitative research explores how human beings understand, experience, interpret and create the social world (Sandelowski 2004). The nature of the research question, which concerned exploring occupational therapists’ views and experiences of evidence-based practice, was therefore deemed compatible with the qualitative research paradigm. Focus groups collect qualitative data from a homogeneous set of people through a focussed group discussion and place a value on the interaction of group members to elicit information and collective viewpoints (Krueger and Casey 2009). Group interviews can have an advantage over individual interviews as they offer insight into how social knowledge can be constructed through the group process (Green and Thorogood 2004).

Participants

The research project gained ethical approval from the University of Brighton and the Local Authority Research Unit. Ethical issues included maintaining the anonymity of participants and mitigating power imbalances between participants and researcher and participants. An invitation to take part in the research and an information sheet were emailed to all occupational therapists employed by the local authority. Fourteen occupational therapists consented to take part from different teams across the local authority area, with a range of experience of working in social care of between six months to thirty years. The sample size allowed for the formation of two focus groups, each with seven participants, to allow for observing patterns and themes emerging within and across both groups (Krueger and Casey 2009).

The researcher

The researcher is employed as a learning and development officer within a local authority organisation and has a key responsibility for supporting occupational therapists in their continuing professional development. The researcher is not managed by the occupational therapy service and has no supervisory or managerial role with occupational therapy staff. The researcher acted as the moderator of the focus group discussions and due to being known to the participants, maintained a reflexive diary throughout the research process to raise awareness of researcher bias (Shaw 2010).

Data collection and analysis

A questioning route was devised, based on a process by Krueger and Casey (2009). Questions included:

- What do you think counts as evidence?

- What do you think is the best evidence?

- How do you develop your knowledge using evidence?

Each focus group discussion lasted one and a half hours. An assistant moderator from the learning and development team, took notes of key points made in the discussions to assist with the analysis of the audio-recordings. A process of thematic content analysis, as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006), was used to analyse the data: familiarisation of the data and transcription, initial coding, collating codes into themes, reviewing the themes before defining and naming them with ongoing analysis, relating the analysis back to the research question and literature in the final report.

Rigour

The study was fully supervised by an academic from the University of Brighton and guided by the quality principles for qualitative research as set out by Yardley (2008). These principles were applied as follows: 1. sensitivity to context by relating the research to theory and literature, being open to alternative interpretations in the data; 2. commitment and rigour through in-depth data collection and analysis; 3. transparency and coherence through the alignment of the research question, the methods used to collect and analyse data, the use of quotes to enable the reader to judge the adequacy of interpretations, and keeping a reflexive journal (Shaw 2010); 4. impact and importance of the study by examining the practical and theoretical implications of the research for occupational therapists working in a local authority setting and the wider professional context.

Findings

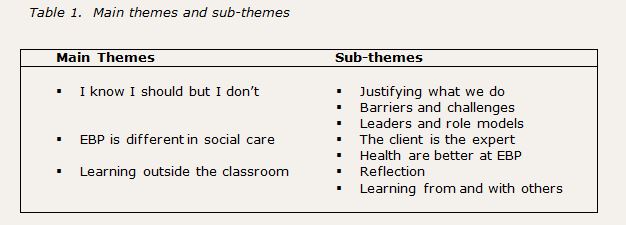

Three main themes were extracted from the data: I know I should but I don’t; evidence-based practice is different in social care; learning outside the classroom. The main themes and sub-themes represent the prevalence of views, the greatest amount of time spent on certain points and those that related directly to the research question.

I know I should but I don’t

Participants in both groups associated the term ‘evidence-based practice’ with the use of research and expressed their concern that research was rarely used to guide their practice. As one participant put it, ‘I know I should but I don’t. This theme runs as the thread throughout the following sub-themes: justifying occupational therapy, the barriers to using research in practice and looking to leaders and role models to develop evidence-based practice within the local setting.

- Justifying what we do

The views of the participants concerning justification of their actions appeared to operate at two levels, dependent on whether research was used to justify the profession or formed part of their day-to-day practice with clients. In focus group one, research was perceived as having a critical role in justifying the occupational therapy profession with some anxiety expressed about the survival of the profession without it:

‘I suppose the scary thing is if there was some seismic change in our role, we would be thinking why wasn’t there more evidence to support it, with things changing as they are’.

Evidence-based practice was discussed as a broader concept in both focus groups, moving away from research as the dominant feature when working with clients. This was described as an intuitive process, rather than a more conscious evidence-based approach:

‘It’s about what you have worked on this week, the client evidence, your own experience, the evidence from your co-workers by having a chat with them. For me, there is rarely a process where I stand there thinking about a particular client, thinking about the best evidence to go forward’

- Barriers and Challenges

Participants in both groups shared their concerns about the lack of time they had for developing their evidence-based practice, with few reporting experiences of using research. Participants in focus group two discussed their frustration at the value placed on quantitative research, which was viewed as being at odds with the ethos of occupational therapy practice and its limitations with the complexities of practice in social care:

‘In terms of day to day practice and the people we work with, it can get a bit messy and although random controlled trials can be useful for a particular subset of people, it’s very difficult to isolate that when you’ve got people with multiple conditions and lots of complications that go on’.

A further barrier was a lack of interest in using research evidence, due to a view that few studies were relevant to occupational therapy practice in a social care setting:

‘What’s the point in reading research on ten people in New Zealand that has no correlation to what we do….it can be hard to find up to date research about community based working, like practice around adaptations in the UK’

- Leaders and role models

In both focus groups, participants highlighted the importance of leaders and role models to engage others with evidence-based practice and demonstrate putting research into practice, with one participant suggesting ‘if other people are passionate, it filters down, doesn’t it?’ Another participant agreed, but reported difficulties motivating peers and getting them to regard evidence-based practice as a priority:

‘You need someone to actually drive that forwards as I don’t think everyone has a person or a few people in that team to actually move things on. Because just setting up the journal club was a bit of pain, to try and get people to allocate time for it and want to do it and get involved with it’.

Participants in focus group one became excited about their idea of having a group of individuals, or a kind of leadership team, which they called a ‘super team’ who would have the necessary time and skills to search for and evaluate research evidence and make recommendations for practice change. The responsibility for putting research into practice was viewed as someone else’s responsibility, as opposed to an individual or shared responsibility:

‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we had an evidence-based practice team who actually had a role of recognising a gap in practice, gathering evidence, formulating it and making a recommendation for a change of practice, just delivering it’.

Evidence-based practice in social care is different

Evidence-based practice in social care was perceived by participants as shaped primarily by clients being seen as the expert in their condition and working in people’s homes, with comparisons made with hospital-based settings.

- The client is the expert

Participants in both groups felt their clients often held the best evidence in terms of their personal experience of their disability, its impact on their day to day lives and the choice and control they wished to exercise with regard to the outcomes they wanted to achieve. This was a strong influence when making decisions, planning and evaluating interventions:

‘If they’ve had a lot of experience living with a health condition for a long time, sometimes they know what’s best. Sometimes we can come in with a big idea about what might change things and make things better, but actually, they’re the expert in it’.

Participants, especially in focus group two, spent some time discussing their experience of clients questioning their interventions and proposing their own solutions, triggering a process of consulting with colleagues and evaluating the risks involved:

‘Looking back, I discussed it with other people, colleagues and involved the moving and handling team and I guess, at the end of the day, I risk assessed, considered her capacity to make that decision and understand the risk’

- Health are better at evidence-based practice

The nature of the work environment was considered a key influence when applying evidence-based practice and in focus group one, this was explored in relation to health-based settings. There was a view that health colleagues were better at being evidence-based in their practice, due to having a medical model approach aligned to the more highly regarded objective, measurable types of research which were perceived as more easily applied in clinical settings:

‘In a hospital, you have distinct evidence-based pathways you follow in a particular way. Whereas in the community, everyone is individual so it makes it more difficult to pick out one bit of evidence’.

‘In a hospital, everyone is in the same environment, so the same practice might apply more. You come across different things in the community’.

Another reason suggested by the group, was that the NHS needed to be more robust in its evidence base, in order to respond to complaints and legal challenge. Their view possibly reflects the impact of media coverage of cases where failures in care and treatment have resulted in calls for disciplinary action and compensation. One participant posed the question ‘does it come down to, perhaps in health, a blame culture and a fear of being sued?’

Learning outside the classroom

Participants in both groups expressed similar views about the role of reflection, learning from doing and talking with their peers as critical to the development of their practice knowledge. Other sources for building knowledge, such as reading books, research articles, participating in courses or conferences were not mentioned.

- Reflection

Terms commonly used by participants in both focus groups included: ‘I think all the time’, ‘I think a lot of my reflective practice is here, in my head’ to describe a continuous mental process of reflecting in the moment or after the event, in order to achieve the best outcomes for clients:

‘I use reflection to look back on my practice to see if I got the best outcome, or if I could have done something differently for a better outcome. Then depending on what your conclusion is, it would tailor my practice when I came to that situation again’.

‘…. even during involvement, you could use reflection to change the way you do something if you think, actually, I am on the wrong course here’.

Linked to this, was the term used in both groups of how knowledge and experience was shaped by a matter of ‘trial and error’ and that this was deemed as a crucial way of building an evidence base for interventions:

‘I think trial and error sometimes. We might have done something with someone else at some point which worked and we can maybe use that and that’s good evidence because if it worked for that person, it may work for this other person. But sometimes it doesn’t, but then you learn from that as well. It’s just as useful’.

- Learning from and with others

There was consensus within and across both groups that learning from and with others was a vital resource for developing their practice knowledge. This moved beyond the idea of the knowledge and experience of immediate team members, to encompass a wide community of practice:

‘I know in our team; we are quite reliant on learning from each other. We throw things to the floor quite regularly and discuss stuff. So learning form others is quite day to day. Joint working with colleagues, carers, families and we can learn from all these different people’.

The knowledge held by health colleagues was also discussed and valued in both groups; particularly their knowledge and information regarding specific medical conditions and prognosis of individual clients:

‘I have worked with the neuro-team quite a bit and I tend to ask their opinion of that person or other people with that condition. They don’t have a crystal ball, but they tend to say this person will probably progress at this rate. So yeah, I will go to them because I value their opinion and evidence as well’.

These interactions possibly reflect those that occur in multi-disciplinary teams where opinions are sought on a case-to-case basis, compensating for occupational therapist only teams in this particular local authority setting. This also links to the earlier notion, that health colleagues were perceived to hold evidence-based opinions.

Discussion and implications

Occupational therapists in the study associated evidence-based practice with research and discussed rarely using research evidence due to time pressures, lack of relevant research and the tensions it presented with client-centred practice, themes that are consistent with the literature (Robertson et al 2013, Upton et al 2014). Research was valued more highly in relation to justifying the profession than in day-to-day practice with clients, when other types of evidence held greater importance, notably the lived experience of their clients and their own and other’s professional knowledge and experience. These findings highlight occupational therapists are not drawing on current research to inform their practice, although it is worth bearing in mind the limited research base in occupational therapy and social care. The reliance on their own and other’s professional knowledge and experience may pose a risk that practice can be outdated as well as subject to personal bias (Hoffman 2010). The provision of support, such as protected time alongside personal commitment, may enable occupational therapists to develop their evidence-based practice and adhere to professional ethics and standards (COT 2010, COT 2011, HCPC 2015).

A broader implication of the findings is that occupational therapists appeared more attuned to an evidence-informed approach, which can be understood as not excluding research, but valuing professional experience and the judgements of practitioners and clients who are in constant interaction with each other (Nevo and Slonim 2011). This suggests the need for further discussion within the profession about whether an evidence-informed approach is more congruent with occupational therapy practice in a social care context, mindful that research utilisation is essential to both evidence-based and evidence-informed practice.

A theme that emerged from the findings, not apparent in previous studies, was the perception by a number of occupational therapists that health colleagues were better at evidence-based practice, due to the nature of their work environment and use of research-based treatment protocols. However, the systematic review of Upton et al (2014) would suggest otherwise, since health-based occupational therapists in numerous studies, reported similar views and experiences to those held by social care occupational therapists participating in this study. Further research that explores the views and experiences of evidence-based practice of occupational therapists working in health and social care settings would be useful and timely, in light of the integration of health and social care (Care Act 2014).

Occupational therapists looked to others to lead on evidence-based practice and research utilisation, with little acknowledgement of individual responsibilities for implementing evidence-based practice, as required in professional ethics and standards (COT 2010, COT 2011, HCPC 2015). The views about leaders link with thoughts from Upton et al (2014 p.36) about the role of ‘knowledge brokers’ who could disseminate up-to-date research, and the findings from an action research study by Morrison and Robertson (2016), which indicated the importance of senior occupational therapists for demonstrating and motivating evidence-based behaviours in new graduates. An action-research project undertaken by Andrews et al (2015 p.4) identified facilitation as a crucial element for developing ‘evidence-enriched practice’ in health and social care with older people. The researchers used the metaphor of making a cake, with the facilitator acting as a ‘good cook’ who supported a collaborative approach to selecting, preparing, mixing and baking different types of evidence to achieve the desired result. The value occupational therapists placed on learning from each other, may lend itself to the development of peer learning approaches. Peer learning is defined as ‘the acquisition of knowledge and skill through active helping and supporting through status equals’ (Topping 2005 p.631), a strategy which may enable all occupational therapists to become ‘good cooks’ of evidence-based practice.

Occupational therapists discussed developing their knowledge through a process of reflecting-in-action and reflecting-on-action (Schon 1987), often describing this as a matter of trial and error, carried out in collaboration with the client. This may be understood as professional artistry, where individuals demonstrate a blend of creativity and expertise built up through reflection and experience (Beeston and Higgs 2001), or as the unique and innovative practice that requires audacity, courage and risk-taking (Higgs and Titchen 2001). Blair and Robertson (2005) highlighted the challenges for bridging the gap between the professional artistry of occupational therapy practice and research, and suggested critical reflection as a way of reconciling the tensions between the two elements. An implication for the organisation is how it can create opportunities for occupational therapists to develop their ability to become critically reflective, such as using supervision for reflective dialogue and critical analysis (Fook and Gardner 2007) and peer-based, critically reflective action learning (Skills for Care 2014).

As noted previously, occupational therapists believed a crucial way of developing knowledge was by learning from and with each other, and this extended beyond their immediate team members to include clients, carers, and health colleagues. This took the form of a community of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991), which was shaped around the particular needs and situations of individual clients. This appears to resonate with the research by Gabbay and le May (2004 p.3) where GPs and nurses integrated evidence from various sources, including ‘opinion leaders’, in negotiation with individual patients through daily networking to form collectively reinforced, tacit guidelines, named as ‘mindlines’. Opinion leaders were identified as trusted individuals, within or outside their teams, who were perceived to hold up-to-date, research-based knowledge in their particular field. For occupational therapists in this study, health colleagues were viewed as external opinion leaders, due to a belief that their practice was underpinned by research evidence. One of the key recommendations made by Gabbay and le May (2004) was to invest in opinion leaders to ensure their knowledge was research-based, alongside a collective responsibility to help strengthen the evidence-base of the ‘mindlines’ created by communities of practice. In connection with previous points, such leaders would need to facilitate collaborative approaches for strengthening the evidence-based knowledge of occupational therapists and the ‘mindlines’ of their communities of practice, in line with individual responsibilities for meeting professional ethics and standards and (COT 2010, COT 2011, HCPC 2015). Key individuals may help to build an evidence-based culture, by modelling the skills, knowledge and behaviours associated with evidence-based practice and facilitating peer learning that can enable all occupational therapists to become evidence-based practitioners.

Limitations

The study involved a small number of occupational therapists in one local authority setting, so it cannot be regarded as representative of local authority occupational therapists as a whole. The participants who volunteered to participate, may have been predisposed to the idea of evidence-based and were also likely to feel comfortable with a group discussion format. One-to-one interviews may have captured more in-depth data about individual viewpoints which can be lost in a group discussion. Team managers were not involved in the study and on reflection; their inclusion may have added a useful dimension to the study due to being an important influence in the practice setting. A further limitation is that the research was carried out by one researcher using a single method of data collection, so the study can only represent one facet of the bigger picture of the subject matter.

Conclusion

The aim of this research study was to explore occupational therapists’ views and experiences of using evidence-based practice to develop their professional knowledge in a local authority setting. Occupational therapists did not draw on research evidence in their day-to-day practice due to time pressures, lack of relevant research, the tension with the client-centred ethos of occupational therapy and its limitations when working with people who have complex needs. Occupational therapists relied on the evidence of the lived experience of clients, their own knowledge and experience, the knowledge of others, including the perceived evidence-based knowledge of health colleagues. Knowledge using these particular sources of evidence was developed through reflection and participation in wide communities of practice which were shaped by the individual client’s needs and situation. Occupational therapists looked to others to lead on developing evidence-based practice in the local setting. Key individuals may help to develop an evidence-based culture, by modelling evidence-based practice and facilitating peer learning approaches that enable all occupational therapists to become evidence-based practitioners. Further research into how occupational therapists construct their knowledge and strategies that can enable them to develop professional knowledge that has a stronger evidence-base is required.

Debbie Ryan Learning and Development Officer OT, West Sussex County Council ; Dr Channine Clark, Principal Lecturer Occupational Therapy, Academic Lead University of Brighton

References

Andrews N, Gabbay J, le May A, Miller E, O’Neill M, Petch A (2015) Developing Evidence-Enriched Practice in Health and Social Care with Older People. Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/developing-evidence-enriched-practice-health-and-social-care-older-people Accessed on: 23.01.16

Beeston S and Higgs J (2001) Professional practice: artistry and connoisseurship. In: Higgs J and Titchen A, eds. Practice Knowledge and Expertise in the Health Professions. Oxford: Butterworth-Heineman,108-117.

Blair SE, Robertson LJ (2005) Hard Complexities – Soft Complexities: An Exploration of Philosophical Positions Related to Evidence in Occupational Therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), 269-276.

Brannigan K (2007) Making sense of research utilisation. In: Creek J and Lawson-Porter A, eds. Contemporary issues in occupational therapy: reasoning and reflection. John Wiley: Chichester, 189-216.

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Brookfield S (2009) The concept of critical reflection: promises and contradictions. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3) 293-304.

Care Act (2014) Care and Support Statutory Guidance. London: DOH. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/315993/Care-Act-Guidance.pdf Accessed on: 25.11.2014

College of Occupational Therapists (2011) Professional standards for occupational therapy practice. London: COT. Available at: http://www.cot.co.uk/standards-ethics/practice-and-process-occupational-therapy Accessed on: 17.10.14

College of Occupational Therapists (2015) Code of ethics and professional conduct. London: COT. Available at: http://www.cot.co.uk/publication/baotcot/code-ethics-and-professional-conduct Accessed on: 17.10.14

Fook J, Gardner F (2007) Practising Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. Open University Press.

Gabbay J, le May A (2004) Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed ‘mindlines?’ Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. British Medical Journal, 329(7473),1013.

Green J, Thorogood N (2004) Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Sage Publications.

Health and Care Professions Council (2013) Standards of proficiency: occupational therapists. London: HCPC. Available at: http://www.hpc-therapistsuk.org/assets/documents /10000512standards_of_proficiency_occupational_therapists.pdf Accessed on: 17.10.14

Higgs J, Titchen A, Neville V (2001) Professional practice and knowledge. In: Higgs J, and Titchen A, eds. Practice Knowledge and Expertise in the Health Professions. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 3-9.

Higgs J, Richardson B, Dahlgren MA (2004) Developing Practice Knowledge for Health Professionals. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hoffman T, Bennett S, Del Mar C (2010) Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions. Churchill Livingstone.

Jay JK, Johnson KL (2002) Capturing complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(2), 73-85.

Krueger RA, Casey MA (2009) Focus Groups; A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4th ed. Sage Publications.

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning; legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University Press.

Morrison T, Robertson L (2016) New graduates’ experience of evidence-based practice: An action research study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 42-48.

Nevo I, Slonim-Nevo V (2011) The Myth of Evidence-based Practice: Towards Evidence-Informed Practice. British Journal of Social Work, 41, 1176-1197.

Petr CG, Walter UM (2009) Evidence-based practice: a critical reflection. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 221-232.

Reagon C, Bellin W, Boniface G (2008) Reconfiguring evidence-based practice for occupational therapists. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 15(10), 428-436.

Robertson L, Graham F, Anderson J (2013) What actually informs practice: occupational therapists’ views of evidence. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(7). 317-324.

Sackett D, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS (1996) Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 312, 71-72.

Sandelowski M (2004) Qualitative Research: The Sage Encyclopaedia of Social Science Research Methods. Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Schon D (1987) Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Shaw R (2010) Embedding Reflexivity within Experiential Qualitative Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 7(3), 233-243.

Skills for Care (2014) Critically reflective action learning: Improving social work practice through critically reflective action learning. Available at: http://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Document-library/Social-work/Action-Learning/Critical-reflective-action-learning.pdf Accessed on 12.04.16

Taylor CM (2007) Evidence-Based Practice for Occupational Therapists. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing.

Topping KJ (2005) Trends in Peer Learning. Educational Psychology, 25(6), 631-645.

Trinder L (2008) Introduction: The Context of Evidence-Based Practice. In: Trinder L and Reynolds S, eds. Evidence based Practice: A Critical Appraisal. Blackwell Science Ltd, 1-16.

Upton D, Stephens D, Williams B, Scurlock-Evans L (2014) Occupational therapists’ attitude, knowledge, and implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic review of published research. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(1), 24-38.

Wenger E (2007) Communities of practice. A brief introduction. Available at: http://www.ewenger.com/theory/ Accessed on: 21.02.15

Yardley L (2008) Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In: JA Smith, ed. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods London: Sage, 235-251.