Abstract

Introduction: English healthcare reforms have prompted occupational therapists to increase efforts to promote their profession to service commissioners (many of whom are general practitioners). Concerns exist that some medical doctors may not fully understand the role of occupational therapists. This research investigated portrayals of occupational therapy and occupations in media aimed at general practitioners.

Method: A critical discourse analysis of 13 on-line and 13 magazine articles from a leading medical publisher.

Findings: Two major discourses were identified: occupational therapy is a valued service – this was qualified by 2 articles considering responses to public spending austerity measures; secondly, occupation is an important aspect of life that can be enabled by medication or restricted by illness – this contrasted to very limited presentation of the therapeutic potential of occupations. Across all findings there was little reference to mental health conditions.

Conclusion: Occupational therapists should welcome acknowledgements of the importance of occupations to people’s health and well-being, and, also the portrayal of occupational therapy as valuable. However, occupational therapists should increase their efforts to explain the following to general practitioners and commissioners: their effectiveness; how occupations can be therapeutic; and the role of the profession supporting people with mental health problems.

Introduction

Following a tumultuous journey involving heated debate and last minute amendments, The Health and Social Care Act was passed into English law on March 27th 2012. Thus England underwent the most significant reform of the NHS since its creation in 1948 (Cairns 2012). Key to the reforms is the concept of ‘commissioning’. General practitioners (GPs) and other health professionals now lead local clinical commissioning groups, choosing what health services they wish to purchase, taking control of 80% of the NHS budget (Charlesworth and Smith 2011). In light of these reforms, various healthcare professional bodies are encouraging their members to promote their role within health and social care and influence commissioners. For instance, the British Association of Occupational Therapists (BAOT) has advised its members that; “by influencing their [commissioners’] decisions you can ensure service users have increased access to occupational therapy services. You can also ensure increased allocation of resources to occupational therapy and more job opportunities for the profession” (BAOT 2011).

Alongside this are concerns that some medical doctors do not understand the occupational therapist’s role (Pemberton 2008, Taylor 2011) – a phenomenon directly observed by the first author whilst a student on practice placements. Previously, Finlay (2004) suggested that ambiguity and confusion about the role of occupational therapists led the profession to a “state of crisis”. The research presented in this article investigates current representations of occupational therapy by examining how the profession is portrayed in articles on the Pulse Today Website (www.pulsetoday.co.uk) for GPs and explores whether or not a relationship between health and occupation is portrayed in Pulse magazine. It is hoped that the findings will be of use to: those tasked with the promotion of the occupational therapy profession; to other professions facing similar challenges; and to researchers interested in the use of Critical Discourse Analysis (Van Dijk 2011).

Literature review

Research related to this topic is dated. Similar studies have not been conducted since the 1990s, when GP fundholding, a very similar structure to the current reforms, was introduced (but not fully implemented). Three studies used questionnaire research to obtain doctors’ perceptions of occupational therapy. Chakravorty (1993) found that awareness in respect of occupational therapy services was lacking in 50% of GPs and 70% of consultants in a then District Health Authority. GPs in Greenhill’s (1994) were unaware of the varying roles of occupational therapists and were, as a result, unable to identify the benefits of an occupational therapy service. Similarly, Darch (1995) reported that none of the 22 GPs who responded were aware of the full range of occupational therapy skills as defined by the College of Occupational Therapists. In all three studies, sample sizes were small, and, as their methods/research questions differed, direct comparisons cannot be made. Recommendations were made on marketing occupational therapy services to GPs such as: maintaining regular contact with updates of new, relevant information; lunch time talks; seminars and/or lectures; and presentations/visits to occupational therapy departments for GP trainees (Chakravorty 1993, Greenhill 1994, Darch 1995). The length of time since these studies were completed and the different policy context suggests the need for new research in this area.

More recently Canadian research, using a multiple case study design, found that understanding of the occupational therapists’ role was essential to support effective integration of the profession into primary care but also that physicians’ (GPs) had a lower level of this understanding than other disciplines (Donnelly et al 2013). Studies investigating other professionals’ perceptions of occupational therapy has been carried out. For instance, Pottebaum and Svinarich (2005) used survey research as a method to capture psychiatrists’ perceptions of occupational therapy, and compared this information with the number of referrals they make. They found that the psychiatrists with least knowledge of the role of the occupational therapist were less likely to refer people to them.

Taylor (2007) typified research on how members of the multi-disciplinary team view the role of occupational therapists as “well worn [and] of little value to a wider audience” (p6). Similarly, in a letter to The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, Creek (2000) recommended that occupational therapists stop worrying about other professions not understanding their role, and “accept that it cannot be encapsulated in a few words” (p405). Finlay (2004) and Fortune (2000) were amongst those who disagreed, calling for further research in this area. It remains the case that published literature on the subject is dated and lacks in methodological diversity. Above all the changed social and political context in the UK and internationally supports the need to explore the complex processes involved in the representations and understandings of the role and practice of occupational therapists amongst other professionals (Reeves et al 2010).

The limited recent literature examining general practitioners’ perceptions of occupational therapy, coupled with the major role GPs are set to take in determining the future of healthcare in England, suggests a need for more research into this topic. Accordingly, this article reports on a study which aimed to answer the following research question:

How are occupational therapy and the link between health and occupation portrayed to general practitioners?

Methodology

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is used by many researchers to understand the social and political influence of text or talk (Van Dijk 2011). CDA not only analyses text (which may be words or pictures), it also theorises on the social and cultural contexts in which texts are produced and interpreted. Since these contexts were considered central to answering the research question CDA was selected as a suitable methodology for this study.

The focus on power in CDA has been developed by the key foundational social theorists (such as Chouliaraki and Fairclough 1999), who have been particularly interested in the ways discourse practices reproduce and/or transform societal power relationships (Lillis and McKinney 2003). Lo-Bartolo and Sheahan (2009) used CDA from an occupational science perspective to analyse an Australian government newspaper promoting employment reforms. Their study makes full use of CDA’s ability to interpret power relationships between groups, claiming “power is the bridging concept between the seemingly unrelated topics of industrial relationships and occupational science” (p410). Other authors use the principles of CDA to explore discourses in texts but do not address power issues to the same extent. Pattison (2006) acknowledges that discourses identified in key UK critical care documents include the power dynamic between professions, families and patients. However, she also explores other discourses such as how the technological environment can act as a barrier to good end-of-life care.

Central to the CDA approach is to acknowledge and make transparent the position of the researcher. One charge levelled at discourse analysis is that researchers read what they want to find in the texts they analyse (Smith 2006). Reflexivity is defined by Green and Thorogood (2009) as “the process of reflecting on both your own effect on the data generated as a participant in the field, and on the social and cultural processes on the research itself” (p286). These authors go on to say that reflexivity is “essential in qualitative research” (p 286). The current study used reflexivity in conjunction with a consistent methodological approach to address Smith’s (2006) critique and to increase reliability. A critical approach starts from a certain stance; here this was related to the first author’s role as a student occupational therapist at the time of conducting a MSc research project and her first-hand experience of the discourses between the groups being studied. It is acknowledged that this background influenced the reading, understanding and interpretation of the texts under analysis.

Methods

Critical discourse analysis “behoves researchers to explain their own analytic methods” (Annandale and Hammarstrom 2010, p574). To aid this, studies within health and social care literature that used principles of discourse analysis as a methodological approach were reviewed. This exercise guided the selection of specific methods detailed below.

Data source selection

According to Corcoran (2005) media plays a “historically unprecedented role in dominating the symbolic ecology of modern life” (pxii). Bell and Garret (1998) consider media to have “a pivotal role as discourse bearing institutions” (p5). Thus, media texts are frequently the subject of analysis for researchers carrying out discourse analysis because of the power exerted on their audiences (Smith 2006). Media texts therefore offer a sound source of data for investigation of how a topic is portrayed to audiences.

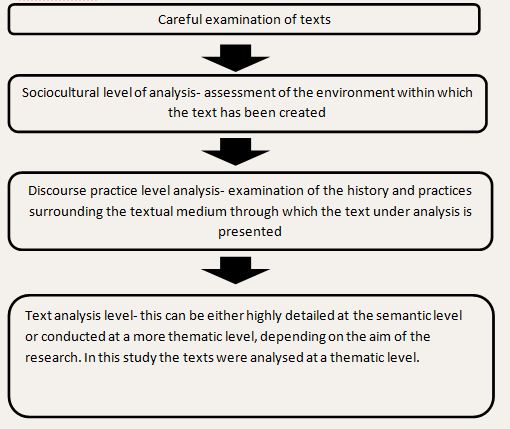

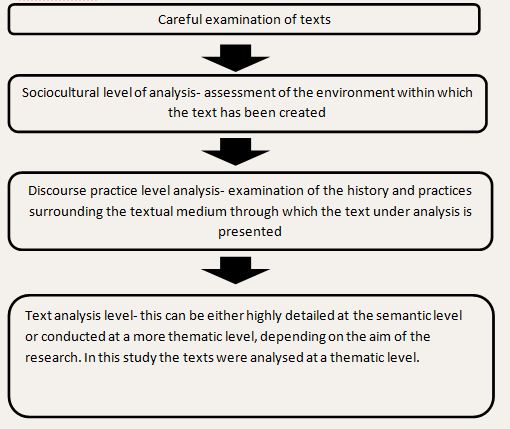

Pulse on-line and Pulse magazine were identified as potential data sources because of their wide reach to their target audience of general practitioners. Further details about these sources and the reasons for their choice are provided in the results section below as this forms part of the sociocultural and discourse practice levels of analysis. There were two research elements; one focusing on portrayals of occupational therapy, and the second on representations of the link between occupation and health. Both elements used Fairclough’s (1995) three tier approach to critical discourse analysis, which was deployed as the first stage of analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig.1: Stage 1: Fairclough’s three-tier approach to discourse analysis

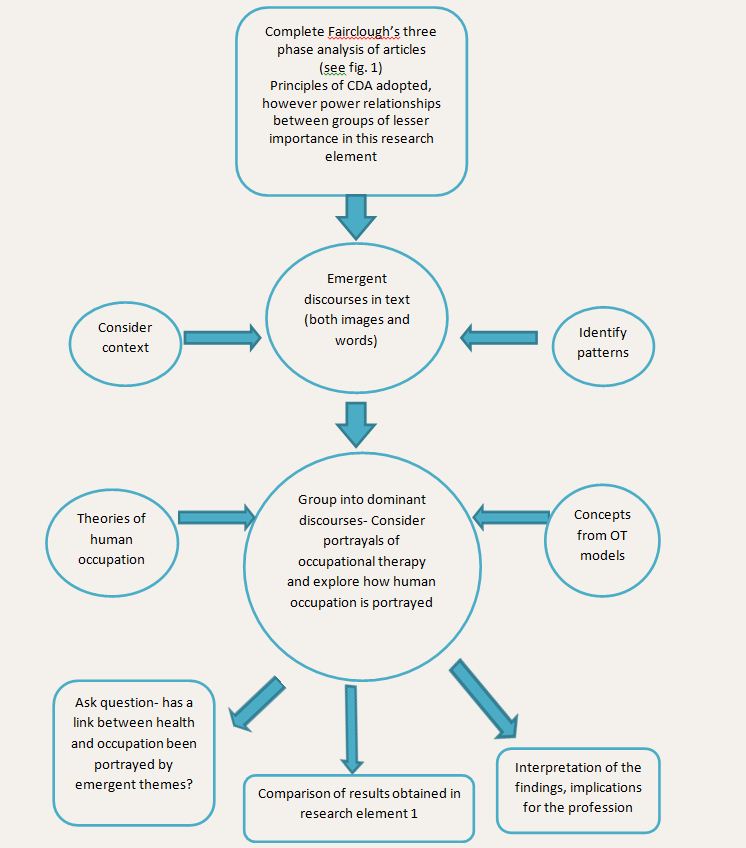

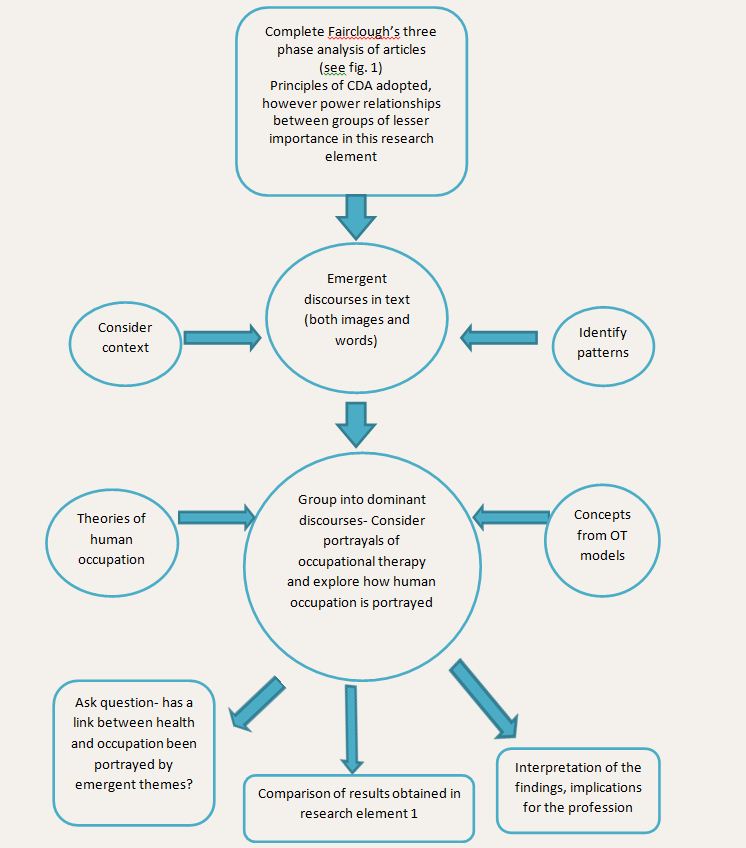

After completing this stage, the analysis took two separate directions for each research element. Research element 1 (RE1), focusing on representations of occupational therapy, considered 13 online articles from Pulse online that contained search term

After completing this stage, the analysis took two separate directions for each research element. Research element 1 (RE1), focusing on representations of occupational therapy, considered 13 online articles from Pulse online that contained search term

“occupational therapy”.

The method of analysis is outlined in figure 2.

Fig. 2. RE1- Approach to analysis of online articles’ representations of occupational therapy

Research element 2 (RE2), focusing on portrayals of relationships between occupation and health, analysed content from Pulse magazine for GPs. Three editions were selected from six months’ of issues immediately preceding the commencement of this stage of the study in order to provide up-to-date data. These editions were selected randomly using an internet based random number generator designed specifically for researchers (Urbaniak and Plous 2011).

Research element 2 (RE2), focusing on portrayals of relationships between occupation and health, analysed content from Pulse magazine for GPs. Three editions were selected from six months’ of issues immediately preceding the commencement of this stage of the study in order to provide up-to-date data. These editions were selected randomly using an internet based random number generator designed specifically for researchers (Urbaniak and Plous 2011).

Those that were selected were from Volume 72 (2012);

The first author carefully read each of these issues. Approaches from occupational therapy were used to support analysis. Several occupational therapy models divide human occupation into the three domains of productivity, leisure and self-care all within the context of a person’s environment (see: Townsend and Polatajko 2007; Baum and Christiansen 2005; Kielhofner 2008). These three components of human occupation were used as a framework when searching for articles related to human occupation. Articles that made reference to at least one of the three domains of human occupation, or to the environmental context of patients’/clients’ lives were included for analysis.

The selected articles were presented to the second author (the first author’s research supervisor) for discussion before conclusions were drawn. In this way the second author adopted the role of a “critical friend”, which is common practice in discourse analysis (Pattison 2006, Nyman et al 2011), by pointing out other possible interpretations and discussing those that had been identified, therefore adding to the reliability of the data. See figure 3 for an overview of the process taken in this research element.

Fig. 3. Approach to analysis of magazine articles’ representations of relationships between occupation and health

Results and discussions

Results from both research elements are presented and discussed below using the format of Fairclough’s (1995) three levels of critical discourse analysis: sociocultural; discourse practice and text analysis (to which greatest emphasis is given) (see Fig 1.)

Sociocultural level of analysis

Pulse magazine’s listing on online journal database host EBSCO lists the publication’s subject areas as a) health and medicine and b) politics and government. Discourse in Pulse publications was largely dominated by political issues, such as the health reforms in England, in which GPs hold a central role, and the hotly contested pension reforms for doctors, over which both hospital doctors and GPs were considering industrial action at the time of writing.

The socio-cultural environment in which these publications were produced was one of political turmoil. The reforms of the NHS have been understood as an attempt to curb the costs of running the health service (BBC 2012). They were produced during a global financial crisis, resulting in recession the UK and much of Europe and consequent austerity measures. To a degree, the publications selected for analysis reflected that heated political environment. Political issues dominated the headlines and draw the reader into the magazine or website using bold political statements and images. See figure 4 for examples.

Fig. 4- Pulse magazine headlines

In the Royal College of General Practitioners Chairman’s report for 2010-2011, the dominance of political discourse among GPs was acknowledged, “when I stood for Chair of Council I didn’t for one moment expect that my first year of office would be dominated so heavily by the Health and Social Care Bill” (Gerada 2011, p2). However, a deeper investigation into media and publications aimed at general practitioners suggests that the fundamentals of general practice – most salient being patient care – remain the primary concern. Gerada’s report (2011) highlighted many key issues the College continued to work on, such as promoting healthy living and supporting people with mental health issues. Beyond the headlines, both Pulse magazines and website devote a significant number of column inches to articles on clinical topics such as case studies, training and other patient-related issues.The research reported in the current study focuses on portrayals of occupational therapy and the link between health and occupation within media sources aimed at GPs. It is discourses relating to this primary focus of general practitioners, patient care, that are of interest. However the wider socio-cultural context of these discourses cannot be ignored as they influence and may help explain their significance and potential impact.

In the Royal College of General Practitioners Chairman’s report for 2010-2011, the dominance of political discourse among GPs was acknowledged, “when I stood for Chair of Council I didn’t for one moment expect that my first year of office would be dominated so heavily by the Health and Social Care Bill” (Gerada 2011, p2). However, a deeper investigation into media and publications aimed at general practitioners suggests that the fundamentals of general practice – most salient being patient care – remain the primary concern. Gerada’s report (2011) highlighted many key issues the College continued to work on, such as promoting healthy living and supporting people with mental health issues. Beyond the headlines, both Pulse magazines and website devote a significant number of column inches to articles on clinical topics such as case studies, training and other patient-related issues.The research reported in the current study focuses on portrayals of occupational therapy and the link between health and occupation within media sources aimed at GPs. It is discourses relating to this primary focus of general practitioners, patient care, that are of interest. However the wider socio-cultural context of these discourses cannot be ignored as they influence and may help explain their significance and potential impact.

Discourse practice level of analysis

The texts under analysis were targeted at General Practitioners working in the UK. After careful consideration of several publications, Pulse was identified as an appropriate media source to draw upon for this research.

The Pulse Today website and Pulse magazine are both owned by UBM Medica. Pulse’s marketing uses the slogan- “at the heart of general practice since 1960” (UBM Medica 2012), suggesting that it is respected and has a wide reach. Accessing information about traffic on the Pulse website is difficult- with only vague details such as “traffic has tripled over the last couple of years” revealed in Pulse’s media pack (UBM Medica 2011). Detail about the distribution of the magazine is readily available- 35,000 copies are distributed weekly (UBM Medica 2011) and a UK-wide medical readership survey conducted in 2011, placed readership of Pulse ahead of its rival, GP magazine, claiming that 88% of GPs have read Pulse at some point over the last year (Hoey 2011). The powerful position Pulse holds in the area of media aimed at primary care professionals is demonstrated by the significant number of stories picked up by national news agencies that first appeared in Pulse or on the website. This was the case for an average of one story per week over the past two years (UBM Medica 2012).

Textual level of analysis

The analysis identified two dominant discourses which are presented and discussed in relation to wider literature below. Also included in the discussion are some important qualifications to these discourses and a consideration of the very limited mental health related content in the texts.

Discourse 1: Occupational therapy is valued by general practitioners

Occupational therapy was almost universally constituted in the texts under analysis in RE1 as a valuable service (and also in one of the RE2 articles). This discourse emerged in the context of the following patient groups/settings:

- Rheumatology

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Housing

- Multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Musculoskeletal conditions

- Falls (RE2)

Most articles referred to occupational therapy in the context of a valued member of the multi-disciplinary team – for instance:

“The management of RA [rheumatoid arthritis] is a lesson in the value of the multidisciplinary team. It is critical that patients have access to physiotherapy, occupational therapy, podiatry, social and psychological support….”

Article 3, RE1.

Another theme identified in RE1 which supported the discourse – was: Occupational therapists can provide beneficial non-drug therapies

This theme emerged in the context of the following patient groups:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Pain in elderly people

For instance:

“The benefits of treating pain are manifold […]. However, older patients may view analgesia with suspicion and take it reluctantly, and the use of non-drug therapies, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, massage therapy and psychological therapy, should be considered”

Article 8, RE1.

The themes identified here, which have all been categorised under “discourse 1”, emerged from over 92% (n=12) of the articles under analysis in RE1. All of the articles from which this positive portrayal of occupational therapy emerged were written by doctors from various disciplines working in both acute and primary care settings. The significance of this will become more apparent to the reader in later discussions examining discourses that emerged from advertisements, which have distinctly different origins.

These are promising findings for those tasked with the promotion of the profession. They contrast to past findings low levels of medical doctors’ understanding occupational therapy (Chakravorty 1993, Greenhill 1994, Darch 1995, Pottebaum and Svinarich 2005), Though direct comparisons cannot be made because these studies were surveys of medical practitioners whereas the current study gives an insight into knowledge of those doctors who write on Pulse’s website, it is notable that in RE1, 38% of the authors were consultants and 62% were general practitioners. The discourse identified suggests that there are influential GPs and hospital consultants who may now value occupational therapy to a greater extent than in the past, and as a result portray the profession in a positive light when authoring work that is aimed at GPs.

The positive evaluation of occupational therapy was qualified by two articles in RE1 included in a theme of service provision in financial austerity. In the satirical article 11, a GP laments the fact that her patients cannot access an occupational therapy service because it has been cut. Without the same sentiment of regret at the loss of service provision, in article 10, Dr. Shane Gordon suggests that commissioners become more creative with their spending, replacing occupational therapists with self-assessment tools:

“Your local authority may be a willing partner in changing models of care provision – remember local government has a 15-year headstart in how to commission services…..They may also hold information to help residents access resources directly, which could equally be accessed through your surgery. This could even include sophisticated tools such as self-assessment for home equipment, traditionally provided through occupational therapy services. This in turn can provide more rapid access to equipment, prevent unnecessary admissions to hospital and maintain the patient’s independence.”

Article 10, RE1

In this time of national financial austerity, and with the NHS reforms handing over control of the purse strings to the target audience of these articles, this theme provides a stark reminder to occupational therapists of the need for GPs to understand their role and value their services. To an extent this theme conveys the same resounding message – that occupational therapy services are valuable in preventing unnecessary admissions and promoting independence. The value placed on occupational therapists however, is different in the second article, as there is an assumption that assessing the home environment does not require the active use of an occupational therapist’s knowledge base or specialist clinical skillset.

Discourse 2: Human occupation from the medical model – Illness restricts, medication enables occupations

Many of the advertisements in Pulse magazine analysed in RE2 displayed clear occupational images – nowhere was a more salient link between health and occupation identified. Advertisements made up 62% of the texts analysed in RE2, and within these 75% revealed two dominant themes:

- Illness restricts occupation: examples include an image of a man unable to go outside and join friends who are eating a meal in the garden because of post herpetic neuralgia

- Medication enables occupation: examples include an image of couple ballroom dancing enabled by anti-inflammatory medication; and the example in Figure 5 below.

Fig. 5: Text 12, RE2. Example of advertisement with clear occupational image- medication enables occupation. (Component of human occupation referenced- play).

According to Wilcock (2005), “occupational therapists are widely associated with a medical model of healthcare in which recognition of how engagement in occupation contributes to health status is poorly understood” (p5). Wilcock goes on to note that she does not condemn the medical model but acknowledges that it’s approach to health differs from that of occupational therapy suggesting that occupational therapists have much to offer medicine. Advertisements for medication are useful sources of information regarding the kinds of ideas and representations about health and illness that are held and promoted within sections of the health industry, whether intended, or implicitly perpetuated using text or images (Foster 2010). The discourses identified portrayed a distinct link between health and occupation, but very much from within the confines of a medical model – occupation is seen as a central part of a person’s life which can either be restricted by illness or enabled by medication. Occupational science as the study of people as occupational beings takes a different approach to this link – that occupation itself can be therapeutic and health giving (Wilcock 2005). The discourses identified rarely portrayed occupation as something that can be therapeutic.

According to Wilcock (2005), “occupational therapists are widely associated with a medical model of healthcare in which recognition of how engagement in occupation contributes to health status is poorly understood” (p5). Wilcock goes on to note that she does not condemn the medical model but acknowledges that it’s approach to health differs from that of occupational therapy suggesting that occupational therapists have much to offer medicine. Advertisements for medication are useful sources of information regarding the kinds of ideas and representations about health and illness that are held and promoted within sections of the health industry, whether intended, or implicitly perpetuated using text or images (Foster 2010). The discourses identified portrayed a distinct link between health and occupation, but very much from within the confines of a medical model – occupation is seen as a central part of a person’s life which can either be restricted by illness or enabled by medication. Occupational science as the study of people as occupational beings takes a different approach to this link – that occupation itself can be therapeutic and health giving (Wilcock 2005). The discourses identified rarely portrayed occupation as something that can be therapeutic.

The analysed advertisements were produced by global pharmaceutical companies with multi-billion dollar annual turnover (Davidson and Greblov 2005). Within this specialised industry, significant resources are invested into marketing in order to maximise the potentially very-high profits that can be secured from developing and marketing a particular treatment (Kotler et al 2005). Context, therefore, is key. These firms are well-versed in the foundational concepts of marketing- that its aim is to make selling superfluous, it is to know and understand the customer so well that the product or service fits and sells itself (Kotler et al 2005). Foster (2010) cautions that “it would be erroneous to suggest that all professionals that encounter these, and other advertisements for medication […] are passive recipients of the explicit and implicit representations contained within them” (p32). However, the same author goes on to remind analysts not to underestimate the power of advertising methods and the numerous ways in which they influence individuals at conscious and sub-conscious levels.

The under-representation of mental health conditions

The virtual absence of content related to mental health was an unexpected finding; especially given the significance that Gerada (2011) had attached to the issue in primary care referred to above. With one exception (Alzheimer’s disease), all articles and texts that were subject to analysis referred to physical health conditions only, making no mention of mental health conditions, either in the context of the occupational therapy role or in the context of a link between health and occupation. None of the advertisements analysed in RE2 were promoting medication to treat mental health problems.

Foster (2010) had used mixed quantitative and qualitative methods to examine the differences between advertisements for psychiatric and non-psychiatric medication. That study found that advertisements for non-psychiatric medication were much more likely to contain images of people participating positively in activities of daily living, whereas advertisements for psychiatric medication tended to portray people in abnormal situations, in a negative way. This suggests that the discourse linking occupation to health and well-being may not have been as dominant had advertisements for psychiatric medication been present.

NHS choices (2012) recommend that the GP is the first point of contact for patients experiencing mental health problems. The BAOT estimates that approximately one quarter of their members work in mental health settings (BAOT 2012). In England, it has been estimated that mental health conditions cost approximately £105 billion a year (Centre for Mental Health 2010), due to loss of earnings and associated treatment and welfare costs. Mental health has therefore been prioritised for economic as well as health related reasons. Considering these facts, the limited content regarding mental health issues has important implications for both the occupational therapist who wishes to remain in valued employment and for the service user. It suggests there may be a lack of consideration of mental health as a whole in media aimed at general practitioners, not just a lack of understanding about the role of occupational therapy in this setting. It is difficult to accept arguments that the general public should see mental health problems in the same light as any other health problem if mental health issues are not presented to general practitioners alongside other health conditions.

The three previously cited studies that examined GPs’ perceptions of occupational therapy conducted in the 1990s all made similar findings regarding doctors’ and general practitioners’ perceptions about occupational therapy and mental health (Chakravorty 1993, Greenhill 1994, Darch 1995). All found that their general level of awareness about the role of occupational therapists was biased towards physical health. It is possible that the current study’s findings may suggest an enduring knowledge gap in GP’s general awareness of mental health issues and not only regarding the occupational therapy role with this client group. This issue merits further exploration given the estimation that about 30% of GP consultations have a mental health component (Kendrick and Simon 2008).

Implications for promotion of occupational therapy and the profession as a whole

The following implications for occupational therapists tasked with the promotion of the profession are suggested from the discourses identified:

- Occupational therapists should welcome the finding that the profession is valued by general practitioners, especially with regard to physical conditions. Marketers are interested in attitudes and beliefs, as they affect buying behaviour (Kotler et al 2005). Emergent discourses suggest the attitude and beliefs of the target audience provides a solid foundation upon which to build awareness of the benefits of occupational therapy.

- Promotion of occupational therapy services to GPs should make use of the shared discourse, revealed in this research, that there is a link between heath and occupation. It must also be considered that “cultural factors exert the broadest and deepest influence on consumer behaviour” (Kotler et al 2005, p256). Occupational therapists should be mindful that the target audience views this link from within the medical model and within a distinct socio-cultural environment. Thus occupational therapists should endeavour to explain and evidence ways in which participation in occupations can be therapeutic in themselves and not only the outcome of other interventions.

- Occupational therapists and other professions should note that as GP led commissioning takes hold, they will be challenged to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of their services, and that GPs may consider alternatives. A recent promotional leaflet produced by the BAOT (See fig. 6) lists the NHS priorities occupational therapy can assist GPs to meet, however the socio-cultural level of analysis suggested that saving money is the fundamental NHS priority underpinning the health reforms, and though implied, this is not mentioned in the leaflet. Occupational therapists may need to present information about the efficiency of their services in a more explicit manner whilst also warning of the dangers of false economies and negative health consequences of failing to use the profession’s skills and expertise.

- There appears a pressing need for occupational therapists to promote their potential role in the area of mental health to general practitioners. The very limited content of information in the texts analysed (and in additional texts in the magazines) related to mental health issues point towards a wider debate than is beyond the scope of this article. What can be implied is the need for occupational therapists to promote the fact that their training enables them to provide therapy for people with mental health problems as well as physical health conditions. The flexibility of occupational therapists should be promoted so that their full skill set can be utilised and valued.

Fig. 6 College of Occupational Therapists promotional leaflet

Limitations of the study and future research

There are a number of important limitations to this study that also suggest directions for future research.

It needs to be stressed again that this study explored representations of occupational therapy and occupations in media aimed at general practitioners. Whilst this may influence and have some relationship to the actual views of GPs further study is needed to explicitly gather GP’s views and perspectives. It should also be acknowledged that this study drew on material from one publisher – albeit a leading one in the field that included much material written by a broad range of medical doctors. Further research using material from other publishers or professional bodies could investigate whether the discourses revealed this study are present in other sources.

Comparison of how another profession is portrayed in similar media could be a valuable undertaking for future research. This, combined with a quantitative approach to examining the number of articles that discuss the interventions of other professionals could contribute rich comparative data. The fact that 13 articles in RE1 were written over a four year period did not account for the fact that many more articles did not mention occupational therapy at all. No quantitative analysis (e.g. counting the number of articles written in this period so a percentage of those that made reference to occupational therapy could be calculated) was undertaken.

Time and word count restrictions meant that regrettably, some more minor discourses have not been reported and discussed in this article. E.g. occupation portrayed as a risk to health (article 4, RE2). These more subtle discourses would make for interesting topics of further research.

The very limited content relating to mental health problems prompted an unanticipated discussion. Further research from an occupational perspective in this area would complement work such as Foster’s (2010), and provide relevant and worthwhile data for the profession in seeking to promote its potential to support people with mental health problems.

Conclusion

The most frequent representation of occupational therapy was as a valued service. This finding should be welcomed by occupational therapists tasked with the promotion of the profession – which one could argue is all occupational therapists. Media articles aimed at general practitioners portrayed occupation as an important aspect of human life which could be limited by illness and enabled by medication. Those designing promotional material should also welcome this finding as it acknowledges the importance of occupation to peoples’ lives. However they should be mindful that this positive relationship between health and occupation was almost universally presented to GPs from within the medical model, and occupation was rarely portrayed as being therapeutic in itself. Thus occupational therapists should continue efforts to explain and develop the evidence for the therapeutic potential of occupations. There was found to be very limited consideration of mental health issues. Occupational therapists should acknowledge that their role in mental health may be less well understood than their role in a physical setting by the GPs to whom they are promoting their services.

Key messages:

- Occupational therapy is portrayed as a valuable service in medical media.

- Occupational therapists should aim to develop acknowledgements of links between occupation and health in medical media.

What the study has added: A useful insight using critical discourse analysis into how occupational therapy and occupations are portrayed in media aimed at general practitioners, who are key players in funding healthcare services.

Cathy White MSc Health through Occupation student and Dr. Josh Cameron Senior Lecturer School of Health Sciences

Reference list

Annandale E, Hammarstrom A (2010) Constructing the “gender specific body”: A critical discourse analysis of publications in the field of gender-specific medicine. Health, 15(6), 571-187.

Baum CM, Christiansen CH (2005) Occupational therapy: Performance, participation and well-being. Thorofare: Slack.

BBC (2012) Q&A: The NHS shake-up. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-12177084 Accessed on 03.06.12.

Bell A, Garrett P eds (1998) Approaches to media discourse. Oxford: Blackwell.

British Association of Occupational Therapists (2011) Promote and influence. Available at: http://www.cot.co.uk/promote-influence Accessed on 09.12.11.

British Association of Occupational Therapists (2012) An introduction to the role of OT in mental health. Available at: http://www.cot.co.uk/mental-health/mental-health Accessed on 13.06.12.

Cairns G (2012) Overhauling health: NHS reform, HIV and patient power. Available at: http://www.aidsmap.com/en/Email-a-friend/tpl/1412195/page/2310747/ Accessed on 04.08.12.

Chakravorty BG (1993) Occupational therapy services: awareness among hospital consultants and general practitioners. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(8), 283-286.

Charlesworth A, Smith J (2011) NHS reforms in England: managing the transition. London: Nuffield Trust.

Chouliaraki L, Fairclough N (1999) Discourse in late modernity: Rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Corcoran F (2005) Forward. In: E Devereux, Understanding the media. London: Sage. Xi-xiii

Creek J (2000) Occupational therapy cannot be defined by one way of thinking or working- letter to the editor from Jennifer Creek. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(8), 405.

Darch G (1995) The future of occupational therapy in the world of GP fundholding. MSc. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

Davidson L, Greblov G (2005) The Pharmaceutical industry in the Global Economy. Indiana: Indiana University Kelley School of Business.

Donnelly C, Brenchley C, Crawford C, Letts L (2013) The integration of occupational therapy into primary care: a multiple case study design. BMC Family Practice 14(1):60. [Epub ahead of print]

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis, the critical study of language. Harlow: Longman.

Finlay L (2004) The practice of psychosocial occupational therapy. 3rd ed. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes.

Fortune T (2000) Is our therapy truly occupational? Letter to the editor from Tracey Fortune. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(7), 350.

Foster JLH (2010) Perpetuating Stigma?: Differences between advertisements for psychiatric and non-psychiatric medication in two professional journals. Journal of Mental Health, 19(1), 26-33.

Gerada C (2011) The Chair’s report to members 2010-2011. London: The Royal College of General Practitioners.

Green J, Thorogood N (2009) Qualitative methods for health and social care. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

Greenhill ED (1994) Are occupational therapists marketing their services effectively to the fundholding general practitioner? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(4), 133-136.

Hoey R (2011) GPs choose Pulse by a growing margin. Available at: http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/newsarticle-content/-/article_display_list/12702180/gps-choose-pulse-by-growing-margin Accessed on 24.05.12.

Kielhofner G (2008) Model of human occupation: theory and application. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Kendrick T, Simon C (2008) Adult mental health assessment. InnovAiT, from the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1(3), 180-186.

Kotler P, Wong V, Saunders J, Armstrong G (2005) Principles of marketing. 4th (European) ed. Essex: Pearson education ltd.

Lillis T, McKinney C (2003) Analysing language in context, a student workbook. Trentham books: Stoke-on-Trent.

Lo-Bartolo L, Sheahan M (2009) Industrial relations reforms and the occupational transition of Australian workers: A critical discourse analysis. Work, 32, 407-415.

NHS choices (2012) Find mental health support. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/mentalhealth/Pages/gethelp.aspx Accessed on 05.07.12.

Nyman SR, Hogarth HA, Ballinger C, Victor CR (2011) Representations of old age falls prevention websites: implications for likely uptake of advice by older people. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(8), 366-374.

Pattison N (2006) A critical discourse analysis of provision of end-of-life care in key UK critical care documents. Nursing in critical care, 11(4), 198-208.

Pemberton M (2008) Trust me, I’m a junior doctor. London: Hodder and Staughton.

Pottebaum JS, Svinarich A (2005) Psychiatrists’ perceptions of occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 21(1), 1-12.

Reeves S, Macmillan K, Van Soeren M (2010) Leadership of interprofessional health and social care teams: a socio-historical analysis. Journal of Nursing Management, 18: 258–264.

Smith JL (2006) Critical discourse analysis for nursing research. Nursing Inquiry, 14(1), 60-70.

Taylor MC (2007) Evidence-based practice for occupational therapists. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Taylor K (2011) Letter to the editor. OT news, 19(10), 4.

Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ (2007) Enabling Occupation II: Advancing occupational therapy vision for health, well-bring and justice through occupation. Ottowa, ON: CAOT.

UBM Medica (2011) Pulse media pack 2011. London: UBM Medica. UBM Medica (2012) Pulse in the news. Available at: http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/article-content/-/article_display_list/11012068/pulse-in-the-news Accessed on 25.05.12.

Urbaniak GC, Plous S (2011) Research Randomizer (Version 3.0) [Computer software]. Available at: http://www.randomizer.org/ Accessed 19.04.12.

Van Dijk TA (2011) Discourse studies, a multidisciplinary approach. 2nd ed. Sage: London.

Wilcock A (2005) 2004 CAOT Conference Keynote Address- Occupational Science: Bridging occupation and health. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72 (1), 5-12.

On 16 October 2004 I attended a match between Rustington and Bosham in Division Three of the Sussex County Football League. Due to the low level of this fixture there was no official admission charge, but instead an elderly gentleman walked around the perimeter of the pitch offering a battered wooden collecting box towards the small number of spectators, with ‘Thanks from Rustington FC’ written on it. The gentleman’s name was Fred Randall, and he was the Club President. At that moment I began to wonder what motivated Fred, and others like him, to volunteer at thousands of other similar clubs up and down what is referred to as the ‘Non League Football Pyramid’ – the term ‘non-League’ referring to those clubs that do not comprise the 92 that constitute the Premier and Football Leagues.

On 16 October 2004 I attended a match between Rustington and Bosham in Division Three of the Sussex County Football League. Due to the low level of this fixture there was no official admission charge, but instead an elderly gentleman walked around the perimeter of the pitch offering a battered wooden collecting box towards the small number of spectators, with ‘Thanks from Rustington FC’ written on it. The gentleman’s name was Fred Randall, and he was the Club President. At that moment I began to wonder what motivated Fred, and others like him, to volunteer at thousands of other similar clubs up and down what is referred to as the ‘Non League Football Pyramid’ – the term ‘non-League’ referring to those clubs that do not comprise the 92 that constitute the Premier and Football Leagues.

The number of roles was varied, with some taking on multiple tasks (Table 1). One volunteer described himself as a “General Dogsbody”. Whilst such a comment may have been tongue-in-cheek to some extent, it might also be interpreted as a sense of being under-valued and taken for granted.

The number of roles was varied, with some taking on multiple tasks (Table 1). One volunteer described himself as a “General Dogsbody”. Whilst such a comment may have been tongue-in-cheek to some extent, it might also be interpreted as a sense of being under-valued and taken for granted.

Motivations for volunteering

Motivations for volunteering

The Serious Leisure Perspective (Stebbins, 2007a) actually incorporates three forms of leisure activity: Serious, Casual, and Project-based (Table 3). Volunteering can take any of these three forms, and often volunteering activity ‘zig-zags’ between the three.

The Serious Leisure Perspective (Stebbins, 2007a) actually incorporates three forms of leisure activity: Serious, Casual, and Project-based (Table 3). Volunteering can take any of these three forms, and often volunteering activity ‘zig-zags’ between the three. Many certainly met the ‘Six Distinguishing Qualities’ of Serious leisure defined by Stebbins (Table 4). Moreover, just as any career ultimately comes to end, a minority were clearly approaching the end of theirs, as they felt the need to step back, “wind down”, reverting to a more casual approach or ‘retiring’ altogether, even if they found it difficult to do so. Such movement, back and forth along a casual-serious leisure continuum, is described by Patterson (2001).

Many certainly met the ‘Six Distinguishing Qualities’ of Serious leisure defined by Stebbins (Table 4). Moreover, just as any career ultimately comes to end, a minority were clearly approaching the end of theirs, as they felt the need to step back, “wind down”, reverting to a more casual approach or ‘retiring’ altogether, even if they found it difficult to do so. Such movement, back and forth along a casual-serious leisure continuum, is described by Patterson (2001).