2017 Emma Donoghue

The University of Brighton is proud to be working in partnership with the Man Booker Prize Foundation again, in the fifth year of our Big Read, bringing contemporary literature to students and staff. For 2017, our Big Read novel was Emma Donoghue’s Room. The Big Read is a campaign in association with Man Booker to encourage first year students of all disciplines to read a Booker-nominated novel together.

The University of Brighton is proud to be working in partnership with the Man Booker Prize Foundation again, in the fifth year of our Big Read, bringing contemporary literature to students and staff. For 2017, our Big Read novel was Emma Donoghue’s Room. The Big Read is a campaign in association with Man Booker to encourage first year students of all disciplines to read a Booker-nominated novel together.

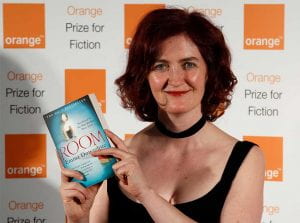

The Big Read 2017 included a free Facebook live event with Emma Donoghue, who gave a short reading and was interviewed by Joe Haddow. See further information about the event on the Man Booker Facebook page.

The Guardian review of Room (2010):

Much hyped on acquisition and by its publisher since (and longlisted for the Booker prize), Room is set to be one of the big literary hits of the year. Certainly it is Emma Donoghue’s breakout novel, but, seemingly “inspired” by Josef Fritzl’s incarceration of his daughter Elisabeth, and the cases of Natascha Kampusch and Sabine Dardenne, it’s hard not to feel wary: what is such potentially lurid and voyeuristic material doing in the hands of a novelist known for quirky, stylish literary fiction?

Much hyped on acquisition and by its publisher since (and longlisted for the Booker prize), Room is set to be one of the big literary hits of the year. Certainly it is Emma Donoghue’s breakout novel, but, seemingly “inspired” by Josef Fritzl’s incarceration of his daughter Elisabeth, and the cases of Natascha Kampusch and Sabine Dardenne, it’s hard not to feel wary: what is such potentially lurid and voyeuristic material doing in the hands of a novelist known for quirky, stylish literary fiction?

It is a brave act for a writer, but happily one that Donoghue, still only 40 but on her seventh novel, has the talent to pull off. For Room is in many ways what its publisher claims it to be: a novel like no other. The first half takes place entirely within the 12-foot-square room in which a young woman has spent her last seven years since being abducted aged 19. Raped repeatedly, she now has a five-year-old boy, Jack, and it is with his voice that Donoghue tells their story.

And what a voice it is. “Ma” has clearly spent his five years devoting every scrap of mental energy to teaching, nurturing and entertaining her boy, preserving her own sanity in the process. To read this book is to stumble on a completely private world. Every family unit has its own language of codes and in-jokes, and Donoghue captures this exquisitely. Ma has created characters out of all aspects of their room – Wardrobe, Rug, Plant, Meltedy Spoon. They have a TV and Jack loves Dora the Explorer, but Ma limits the time they are allowed to watch it for fear of turning their brains to mush. They do “phys ed” every morning, keep to strict mealtimes, make up poems, sing Lady Gaga and Kylie, and most importantly, Ma has a seemingly endless supply of stories – from the Berlin Wall and Princess Di (“Should have worn her seatbelt,” says Jack) to fairytales like Hansel and Gretel to hybrids in which Jack becomes Prince Jackerjack, Gullijack in Lilliput: his mother’s own fairytale hero. And really, what is a story of a kidnapped girl locked in a shed with her long-haired innocently precocious boy if not the realisation of the most macabre fairytale?

Donoghue has not been so crass as to make light of their plight: at times it’s almost impossible not to turn away in horror. When Ma’s kidnapper comes to the room in the evening, she makes Jack hide in the wardrobe, where he listens as they get into bed: “I always have to count till he makes that gaspy sound and stops.” Ma has days where she is “gone” to blank-eyed depression and Jack, left to his own devices, reveals: “Mostly I just sit.” But the grotesque is consistently balanced with the uplifting and there is a moment, halfway through the novel, where you feel you would fight anyone who tried to wrestle it from your grasp with the same ferocity that Ma fights for Jack, such is the author’s power to make out of the most vile circumstances something absorbing, truthful and beautiful.

Donoghue has not been so crass as to make light of their plight: at times it’s almost impossible not to turn away in horror. When Ma’s kidnapper comes to the room in the evening, she makes Jack hide in the wardrobe, where he listens as they get into bed: “I always have to count till he makes that gaspy sound and stops.” Ma has days where she is “gone” to blank-eyed depression and Jack, left to his own devices, reveals: “Mostly I just sit.” But the grotesque is consistently balanced with the uplifting and there is a moment, halfway through the novel, where you feel you would fight anyone who tried to wrestle it from your grasp with the same ferocity that Ma fights for Jack, such is the author’s power to make out of the most vile circumstances something absorbing, truthful and beautiful.

Thereafter, the setting moved to “Outside”, the relationship diluted by alternative voices, by the number of new things with which Jack has to deal, the novel loses some of its intensity and has the more familiar feel of the naive child narratives of Roddy Doyle and Mark Haddon. Jack’s introduction to the confusing world of freedom is handled with incredible skill and delicacy – as is his first separation from Ma. But the novel, like Jack, now has to follow a more logical and straightforward path.

For me, the rhythm of Ma and Jack’s speech bears traces of the author’s native Irish brogue, though the second half reveals the setting to be America (Donoghue now lives in Canada). But this only adds to the strange, dislocating appeal of Room. In the hands of this audacious novelist, Jack’s tale is more than a victim-and-survivor story: it works as a study of child development, shows the power of language and storytelling, and is a kind of sustained poem in praise of motherhood and parental love.