Jan

2019

Reflecting on Pedagogy

This blog will explore the key finding from the Bold Beginnings Report (Ofsted, 2017: 5) ‘Reading was at the heart of the curriculum’, with reference to and reflection upon previous classroom experiences.  Within the Early Year’s Foundation Stage (EYFS, DfE, 2012), reading underpins the prime area of learning of Literacy, recognised as the foundations for development of language, comprehension and vocabulary (Ofsted, 2017).

Within the Early Year’s Foundation Stage (EYFS, DfE, 2012), reading underpins the prime area of learning of Literacy, recognised as the foundations for development of language, comprehension and vocabulary (Ofsted, 2017).

SBT1 highlighted reading as being at the heart of the Reception classroom. An effective pedagogical practice observed was the ‘5 a day’ approach, aiming to read 5 stories a day to children. Some may view this pedagogical approach as forceful (Park et al, 2015), however this role model with a love, motivation and understanding of the value of reading provides exposure for children to experience a wide range of literature texts, genres, compositions, language, concepts, print and grammar. Comments including ‘This is my favourite book”, “I like reading stories” and “Reading stories makes me happy” highlight enjoyment, motivation and a desire to voluntarily read (Kucirkova, Littleton and Cremin, 2017). ‘This growing engagement with books and the enjoyment of narrative is the key to young children’s reading development’ (Collins and Svensson, 2010:82).

Fundamentally, opportunities for children to discuss, question and share ideas and experiences are provided, promoting children’s curiosity, motivation and engagement in reading for pleasure. ‘Reading and discussing the same texts enables children to articulate these processes, to recognise what they do as readers and why, and to learn from what others say’ (Ofsted, 2017:5). The children appear to enjoy the routine and structure of being read 5 stories a day, showing interest, attention and enjoyment of the literature. Although this pedagogical practice appears to be effective, the class teacher faces the challenge of day to day constraints of teaching, meaning the ‘5 a day’ sometimes gets pushed aside. Despite this, children notice when 5 books haven’t been read, where every effort is made the next day to align with the routine of the approach.

SBT1 values a child’s wider eco-system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) when providing for reading opportunities, where parents, carers and friends are invited in every Friday afternoon before the day ends to read with their children, creating a shared opportunity to value and promote a love for reading (Li, Martin and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung, 2017). ‘The reciprocal nature of children’s literacy learning and how what is learned at home comes into school, and what is learned in school also shows up for the children as they interact with family members…’. Thus, mutual relationships can exist between school, home, and community literacy practices…’ (Saracho, 2016:630).

Within SBT1, ‘Naughty Bus’ was used as a stimulus to support children with Autism with a heavy interest in vehicles to engage in play across additional areas of development. The story provided context and purpose for engaging in a variety of ways, extended to making a bus using loose parts materials, drawing pictures of vehicles and sharing experiences of travelling in vehicles. Providing these opportunities around the text captured enjoyment, engagement and reader response (Huntsinger, Jose and Luo, 2016), valuing the children’s interests to stimulate and motivate learning.

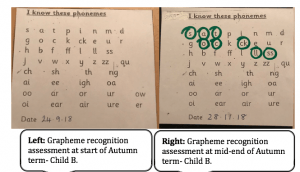

Some pupils may not be developmentally ready to read words (Ofsted, 2017), impacted by early experiences and abilities to identify graphemes with corresponding sounds and to master the decoding process- how letters and sounds are embedded, segmented and blended (Park et al, 2015).

Daily phonics sessions using Big Cat Phonics, Funky Fingers activities and developmentally appropriate tasks provide children with challenging yet engaging and appropriate experiences to grasp and master the phonological structure of reading. Pupils are assessed very frequently in recognition of graphemes and reading, which may put pressure on children who are struggling. Despite this, daily phonics sessions revisit all graphemes and phonemes previously covered, meaning children can continuously be reminded and practice unfamiliar and more difficult phonemes, cementing into their understandings.

The choice to read a story to the class allows children to actively construct and communicate a deeper level of understanding through reference to past experiences, interests and using illustrations in (Piaget, 1958; Glazzard et al, 2010) of literature, whether the words are systematically read or not. This experience builds the foundations for understanding that marks on the page represent meaning, as Goouch and Lambirth (2017) highlight hearing books read and early reading opportunities transform marks on the page into people, worlds and concepts.

A recent Ofsted visit to my school concluded a need for more consistent, quality phonics sessions and reading/writing opportunities across KS1. This may underpin the emphasis and value the class teacher places on reading within the Reception classroom alongside the benefits of reading, forming the foundations and building blocks for crucial literate skills required for the transition to KS1 and for lifelong learning. I aim to incorporate the pedagogical approaches adopted by my class teacher within my own classroom, to inspire, motivate and engage children’s learning to flourish as a confident, competent reader.

Reference List:

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Collins, F. and Svensson, C. (2010) If I had a magic wand I’d magic her out of the book: the rich literacy practices of competent early readers. Early Years: An International Research Journal. Vol. 28(1), p. 81-91.

Department for Education (2012) Development Matters in the Early Years Foundation Stage. London: Early Education.

Glazzard, J., Chadwick, D., Webster, A. and Percival, J. (2010) Assessment for Learning in the Early Years Foundation Stage. London: SAGE Publications.

Goouch, K. & Lambirth, A. (2017). Teaching Early Reading & Phonics: Creative Approaches To Early Literacy. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Huntsinger, C. S., Jose, P. E., & Luo, Z. (2016). Parental facilitation of early mathematics and reading skills and knowledge through encouragement of home-based activities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37(1), 1–15.

Kucirkova, N, Littleton, K. and Cremin, T. (2017) Young children’s reading for pleasure with digital books: six key facets of engagement.Cambridge Journal of Education, Vol.47(1), p. 67-84.

Li, H., Martin, A.J. and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. (2017) Academic risk and resilience for children and young people in Asia. Educational Psychology, Vol 37(8), p. 921-929.

Ofsted (2017) Bold Beginnings: The Reception curriculum in a sample of good and outstanding primary schools. Manchester: Ofsted. Available at https://schoolsweek.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/28933-Ofsted-Early-Years-Curriculum-Report.pdf. (Accessed on 28 November 2018).

Park, Y., Chaparro, E.A., Preciado, J. and Cummings, K.D. (2015) Is Earlier Better? Mastery of Reading Fluency in Early Schooling. Early Education and Development, Vol. 26(8), p. 1187-1209.

Saracho, O.N. (2016) Literacy in the twenty-first century: children, families and policy. Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 187(3), p. 630-643.