Jan

2019

Computing in Primary School

The recent computing task involved four Reception children with differing levels of needs. Observations highlighted the children’s levels of development, previous experience with technology concepts and interests. I decided to introduce concepts of computing within a context of interest, as Marsh (2005) advocates children experience increased motivation to engage in an activity when components compliment their interests. Stevens-Smith (2016) similarly considers children’s interests as an ‘intrinsic motivator’ to engage with an activity through feeling a sense of empowerment and familiarity, increasing the likelihood of children fulfilling their maximum learning potential (Maslow, 1943; Lester et al, 2010).

Berry (2014) would argue, in order to understand and learn about algorithms, children need to experience them by creating them. Aligning with this view, Piaget (1958; Gray and MacBlain, 2012) values active experiences to construct deeper understanding and meaning. Consideration of these perspectives placed value on physical, real world experiences for children to understand and construct meaning of computing concepts, acting as the rationale for the activity idea.

Observations highlighted a strong interest in outdoor play and making models using Duplo to incorporate into their play. I came up with the idea of children making their own remote control (out of Duplo) and having to take turns to use their control and directional language to direct another person to an agreed location in the garden.

The objective of the task therefore focused on modelling, scaffolding and teaching children to use a sequence of instructions to travel from a starting location to an end location, aligning with their interests to potentially stimulate their learning.

The Early Years Foundation Stage (DfE, 2012) children need to ‘…select and use technology for particular purposes’ (DfE, 2012: 42) to reach the ELG. Although real, physical technology was not at the heart of this task, the technological concepts remain the same, using the processes within computing to solve real-world problems (Turvey et al, 2016). The activity provided opportunities to understand technology can be used in different contexts and how to create algorithms.

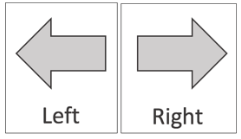

During the introduction, children demonstrated by moving their bodies the meaning of directional terminology, mainly forwards and backwards. I then introduced the directions of left and right, creating key cards for children to refer to as a prompt.

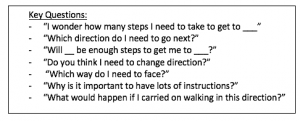

I modelled the activity by being the ‘walker’, where open-ended questions were asked to the children to stimulate their thinking and provide me with instructions to travel to an end location: The children each had a turn at being the ‘walker’ and the ‘directioner’.

The children each had a turn at being the ‘walker’ and the ‘directioner’.

After demonstrating the activity, I recognise the importance of modelling tasks to provide a visual example of how to do an activity and what key skills/language may be involved in achieving this (Bandura, 1977). Children appeared comfortable in identifying the terms forward and backwards to the correct direction, which may be due to the terms being familiar to children’s play experiences.

Upon reflection, I may have overestimated children’s understandings of the terminology ‘left’ and ‘right’, as children appeared to find it difficult to correctly identify which term matched which direction when giving instructions. Despite this, modelling this language and providing a visual to refer to means children have had exposure to richer, deeper concepts involved in creating algorithms.

Children showed high enthusiasm in using their own creations/controls to assist in directing another person. Following the activity, observations within natural, free flow play highlighted children using the concept of controls and physical control creations. This made me feel a sense of achievement as the foundations for algorithms had been taught, scaffolded and practiced, whereby children showed motivation and enthusiasm to incorporate elements of this within their own play.

This activity has highlighted value on observing interactions and planning for learning experiences which are memorable, meaningful and motivating for children to engage, feel inspired and fundamentally provide the foundation learning experiences which assist in ensuring all children fulfil their maximum learning potential (Cullen, Harris and Hill, 2012).

Reference List:

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. New Jersey: Prentice- Hall.

Berry, M. (2014) Computing in the national curriculum; a guide for primary teachers [online] Available: < http://www.computingatschool.org.uk/data/uploads/CASPrimaryComputing.pdf > (accessed 22/10/18)

Cullen, R., Harris, M., Hill, R. (2012) The Learner Centred Curriculum: Design and Implementation. CA: John Wiley and Sons.

Department for Education (2012) Development Matters in the Early Years Foundation Stage. London: Early Education.

Gray, C. and MacBlain, S. (2012) Learning Theories in Childhood. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Marsh, J. (2005) Digital Beginnings: Young children’s use of popular culture, media and new technologies. Literacy Research Centre, University of Sheffield.

Stevens-Smith, D.A. (2016) Active Bodies/Active Brains: Practical Applications Using Physical Engagement to Enhance Brain Development. Strategies, a Journal for Physical and Sports Educators, Vol.29(6), p. 3-7.

Turvey, K., Potter, J., Burton, J., Allen, J. and Sharp, J. (2016) Primary computing & digital technologies: knowledge, understanding & practice. London: Learning Matters.