Month: March 2018

The use of Videos in the ELT classroom

Week six was all about videos and their use in the ELT classroom. Considering I feel I am more of a visual learner, I found what we did in class these two past weeks very interesting. I have been using videos in my classes ever since I finished my CELTA and have found that students usually enjoy lessons based on videos. What I also found important during this session and after doing the reading for the week was how we actually use videos in class and what we do or could do with them.

While reading Ben Goldstein’s article ‘A history of video in ELT’, I identified myself with a lot of what he says about video use in the ELT classroom. Firstly, the ‘before’, ‘while’ and ‘after’ video activities; as Goldstein mentions, the ‘before’ stage ‘activates schema’, the ‘while’ stage ‘focuses the learner on comprehension or language-based tasks’ and the ‘after’ stage’ is when students ‘respond affectively to the material, reflecting on it or discussing it in some way’ (2017). I can think of many times I’ve used videos like that in my classes and I do agree that the ‘after stage’ leaves space for a more ‘creative response’ from students (Goldstein, 2017). Another thing mentioned in his article was the use of documentaries and news in class as ‘authentic’ materials, which are sometimes tweaked to facilitate students’ needs, and then they become ‘semi-authentic’. This in particular rings a bell as a book I’ve been using in my upper-intermediate classes, which also includes BBC talks and footage taken from documentaries, is ‘Speak Out’. I really like how activities around the video are structured for the students to practise various skills; however, I think it’s the job of teacher to exploit videos accordingly, depending on their students’ needs.

Moving onto more current trends, Goldstein talks about using videos to encourage ‘a more critical response’ from students. I thought this argument was particularly interesting as I do believe in the idea of critical thinking and moving away from just doing language tasks based on videos. Language can also emerge and be taught by asking students to dig deeper and think of what they ‘ve watched in a more critical way. A useful idea mentioned in Goldstein’s article is that of using ‘YouTube’ videos to ‘evaluate online comments’ and ‘develop a more critical interpretation’ of what the students see (2017).

Finally, I really liked Goldstein’s argument about the exploitation of video materials in the future. He claims it ‘should become less mechanical and more creative’ and that it is expected that videos ‘will be put into the hands of learners, thus giving them responsibility for their own learning’ (Goldstein, 2017). This idea of student autonomy has been a major realisation for me during the course and the materials module. Whatever we do in our classes should be a lot more than just using materials to teach a class. Materials, should be a tool we use or something we create to lead our learners to autonomy and thinking more critically. Lyricstraining.com, for example, is a tool where students get the chance to type the lyrics of a song while watching its video. I’ve been using ‘Lyricstraining’ in my classes and my experience has shown me that students do enjoy activities like this. However, if we want to talk about more creative and less mechanical tasks, a great idea would be to set gap-filling exercises as homework and ask students to ‘evaluate the video and discuss how they would remake it and why’ in class as an ‘after’ stage activity (Goldstein, 2017).

Some recent personal experiences of using videos in class involve a task-based lesson I planned for my third assessed observation. I created a video with a colleague where we pretended to be a travel agent and a customer. We performed a model dialogue and I used this video with the sound off to activate schemata at first and later on for students to see what a model dialogue looked like and re-perform the task. My students’ feedback at the end of the class was that the use of video had helped them perform the task better, pick up language mentioned in our dialogue, which they then used to recreate their own dialogue. This whole lesson and our session on videos generated another teaching idea; students could choose a topic of their interest and create their own videos accompanied by a dialogue. As Motteram (2011) points out, ‘this can progress quite quickly into developing significant digital skills for the learners, as well as making use of language to carry out the activities’. Adding to this, I’d say that teachers can also develop their digital skills with the help and knowledge of their students. It’s quite common for students to be familiar with so many different technologies nowadays, and we can definitely learn a lot from them. In fact, being open, giving learners the space and time to show what they know might motivate them more and boost their confidence, which could eventually lead to them being more active contributors in class.

TED talks have also proved useful in my lessons and my students usually have creative discussions about the topics they watch. I can remember using videos taken from TED talks which then generated a debate, which also led to vocabulary lessons on expressing opinion, agreeing/disagreeing, negotiating and persuading. Additionally, after reading Goldstein’s article, the idea of students evaluating comments, answering them or adding their own could definitely move the whole class to a more creative spectrum where learners respond critically to what they ‘ve watched.

Last but not least, Virtual Reality and ‘Aurasma’ were mentioned in our sixth session. One of my classmates demonstrated a listening task he’d created and used in one of his classes. It was really fascinating to see how we, teachers, can exploit new technologies and make a task/activity more interesting and creative. As a matter of fact, technology has been advancing and will continue to do so in the future. I think it’s paramount to familiarise ourselves and our students with innovative ways of doing things in class, especially in a world where young generations grow up using technology from an early age.

I definitely took a lot from this session and the reading I did for this week. It was really helpful to have all these conversations with people who work at different schools as well. Every school provides different facilities, but even when advanced technology facilities are not provided, it’s important to share ideas about how we could teach our students just by using a smartphone and an application on our devices. ‘Aurasma’ or ‘HP Reveal’, as it’s now called, is one of them and I’ll definitely try and make use of it in my future classes.

References

Goldstein, B. (2017) A history of video in ELT. In: Donaghy, K. & Xerri, D. (eds). The Image in English Language Teaching. Floriana, Malta: ELT Council. pp. 23-32.

Motteram, G. (2011). Developing language-learning materials with technology. In: Tomlinson, B. (ed). Materials Development in Language Teaching. (2nd ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 303-327.

The power of visuals

Week five was one of the most interesting ones. The session was about visuals and I feel I can relate a lot to this. I believe myself to be more of a visual learner, and I still remember our SLA session with Simon last year, when we did a quiz to find out what kind if learners we are. You can imagine what my result was! Even though we concluded that no one is just one type or learner, I still find visuals stimulating and that they can generate long discussions and interesting lessons.

Our session started with Paul showing us different pictures and asking us to talk about how we interpreted what we saw. It is amazing how people perceive things they see so differently from one another and how each one of us responds to different pictures. It is obvious that when someone creates a picture, they have got a particular idea in the back of their minds, but it is even more fascinating to see how other people interpret them or what some people see that others may have failed to notice. That made me realise how many things we could do with a simple visual in our classes. How many conversations and class discussions we could have with our students, along with vocabulary that could be taught, which could then lead to a reading or writing exercise!

What we can do with visuals also made me think of the reading I did before getting to class. I read Hill’s ‘The Visual Elements in EFL Coursebooks’ and I agree with a lot of the points he makes. Talking about how visuals are used in course books, and after conducting a research, Hill concludes that ‘…the ELT publishers, editors and authors think that it is more or as important to provide attractive space-filling accompanying illustrations in their course books than it is to provide pictures with related activities’. (Hill, 2013). I totally agree with this observation as I have used many books in the past where activities were accompanied by visuals only to make them look more appealing instead of relating to the activity directly.

Another point mentioned in Hill’s book that caught my attention was that of Pit Corder’s distinction between ‘talking about’ a picture and ‘talking with’ a picture (Pit Corder, 1966). I found this part of the reading very interesting as this is a skill I actually try to teach my FCE students. In part 2 of their speaking exam they have to compare and contrast pictures and move away from merely describing what they see. They have to relate what they see to what they know and, therefore, ‘bring their own reality to the lesson’ (Hill, 2013). An example I usually give them to help them develop this particular skill is that of visiting an art gallery with a friend, looking at famous paintings together and then having a conversation about ‘what’ they saw and ‘how’ they would interpret what they saw. People’s descriptions of what is shown in a picture might be similar but the feelings and thoughts a picture can generate may differ from person to person. Therefore, pictures and visuals in ELT materials could be used to stimulate students’ critical thinking rather than simply make a book look more attractive.

Another interesting part of this session was when Paul asked us to describe how we would teach the ‘Present Perfect’ aspect and how we would make it visually engaging. The first thing that came to mind was the use of timelines and retrospective eyes. By simply drawing an eye on the board we could refer to the present and past and many different uses of the present perfect could be elicited and taught. How fascinating! Just by drawing a simple eye on the board!

Personally, I love using visuals in class. Every time I get the chance to do so, I ask my students to refer to photos: sometimes to get the main idea of a text, to generate discussions about various topics and to make grammar more fun. Another thing I’ve learnt through teaching is that you don’t have to be great at drawing to use visuals in class. You can always ask your students to do the work! One of my favourite lessons to teach, for example, is reported speech because I get to to see my students create their own comic stories. I love that! It’s their time to be creative and I take advantage of it to take a step back and just monitor their work. Below are some pictures I took last summer when we did reported speech with my upper-intermediate class. After discussing how to report other people’s words, the students were given a text in reported speech and they had to change it into direct speech by following the story events and creating their own visual version of it.

Reported speech, as my students’ feedback has shown so far, is quite a ‘difficult’ and ‘demanding’ grammatical point. Students need to memorise rules related to changes from direct into indirect speech as well as a number of reporting verbs which follow various structures, so every time reported speech appears in a text book my first thought is that I don’t want to bore my students with endless lists of rules. Why not draw then and learn while having fun? Most of the time my students’ first reaction when I mention drawing goes like that: ‘Oh no! My drawing is terrible!’, to which I reply: ‘It can’t be worse than mine!’. The last time I used this activity in class the initial reactions were exactly the same until the students got down to it. While monitoring, I noticed giggles, students trying their best to create nice drawings, co-operation and people advising each other as well as a positive attitude towards a grammatical topic they usually frown upon. A close look at the pictures below and one can see that their response to the task was actually impressive. The changes from indirect to direct speech were grammatically correct and, at the same time, the students seemed to enjoy the activity. Killing two birds with one stone, I’d definitely say yes to that!

Reflecting on what I did in class one year ago and having had a session on visuals on the Diploma course I can now see how I could take this whole lesson a bit further. Comics could generate story writing; students could delete the speech bubbles, look at the drawings or create new ones, exchange them with their partners’ drawings and write a story using narrative tenses based on the pictures they see. Another idea would be to use the dialogues in a comic story to do some role-playing which would mean speaking practice, and which could then lead to pronunciation, sentence stress or intonation. Finally, this could also be an interesting class for students who struggle with spelling and punctuation. The use of enjoyable and interactive activities such as comics could help students make small steps towards better literacy skills. Not to mention the amount of vocabulary related to feelings that could be taught simply by looking at facial expressions within a comic story. I can’t believe how many things I can see now that I couldn’t see before!

Don’t we all love visuals! 🙂

References

Hill, D. A. (2013). ‘The Visual Elements in EFL Coursebooks’ in Brian Tomlinson Developing Materials for Language Teaching. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Pit Corder, S. (1966). The Visual Element in Language Teaching. London: Longman.

Adapting and Supplementing Materials

Week four was about adapting and supplementing materials. The session started with the definition of the word ‘metaphor’ and moved on to metaphors related to coursebooks. I had never thought of a metaphor to describe a coursebook before, but if I had to choose one, I’d probably say that coursebooks are like traffic lights. To me, a green light is the moment when a teacher finds exactly what they’d been looking for in a book, and so they use pieces of material straight away without any adaptation. A red light is the exact opposite. It could signify moments when teachers feel that specific materials might not be very effective for their learners and, therefore, adaptation/supplementation takes place. The yellow light lies somewhere in between. As I see it, novice and experienced teachers would react differently to a yellow light. Novice ones would probably stop to think and plan of what and how they would adapt/supplement whereas experienced teachers would probably act on top of their heads. They would adapt/supplement quite fast based on their experience. This last idea reflects on what McGrath claims about more experienced teachers being more ‘flexible’ when adapting. More specifically, he states that ‘this flexibility may derive from the possession of a wider repertoire of options or the confidence that comes with experience – knowing how to deal with a problem one has encountered before’ (McGrath, 2013).

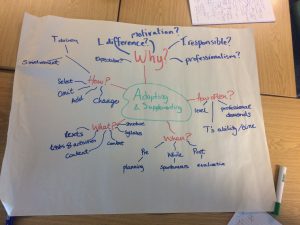

Later on during the session we got into groups with students who had read the same articles and then into groups with people who had read different ones. Our task was to design a ‘seminar’ to present these ideas of adapting and supplementing to novice teachers. I found this part of the class quite exciting as I would like to move on to teacher training in the future and I strongly believe in exchanging experiences with other teachers. My group decided to focus on the following questions:

1. Why do teachers adapt/supplement materials?

2. How do they do it?

3. What do they adapt/supplement?

4. When and how often do they adapt/supplement materials?

As for the whys we thought that teachers adapt or supplement materials due to learner differences, to show professionalism, to show how responsibly they can respond to their students’ needs, how motivated they are, to increase their learners’ motivation as well as due to the fact that they are sometimes expected to do so. In terms of the hows, we all agreed on the ‘omit’, ‘select’ and add’ process as well as the fact that adapting or supplementing could be teacher driven but students could also be involved. Personally, I like involving and asking my students’ opinion on materials, especially for my exam classes. They all have an ultimate goal when it comes to their studies, and at the end of the day it’s all about achieving these goals together, as a team. Finally, we agreed that adapting/supplementing could also mean changing materials completely when they do not seem to ‘work’ for our students.

We then talked about what to adapt or supplement and we came up with: texts, tasks and activities, the structure of what we want to teach, the content or context as well as the syllabus. A sound grasp of one’s class can help identify what we should be adapting/supplementing to help our students. As for when teachers adapt or supplement materials, we thought teachers usually follow the ‘pre-while-post’ process of doing so. ‘Pre’ in this case means planning before adapting and it could be connected to less experienced teachers, ‘while’ is usually spontaneous and is related to more experienced teachers, and ‘post’ would be more of being a reflective practitioner, and in this case would be related to being ‘evaluative’. The latter appeals a lot to me, especially after doing this course. I think that getting feedback from students as well as reflecting on how we teach, the materials we use and they way we use them should be part of our everyday practice to facilitate our students’ needs as well as our own professional development.

Last but not least, the idea of ‘how often’ we adapt or supplement stemmed from my own personal experience and my workplace. At our school we have a policy of using the book 60% of the time. The rest 40% of it is when we can adapt/supplement. Therefore, professional demands could affect how often we supplement as could the level of our students and the teacher’s ability and time.

A recent example was during my second assessed observation, which was a reading lesson in my FCE class. Knowing my students’ strengths and weaknesses, I specifically chose a type of reading they all found difficult and always moan about. However, I chose to tweak it slightly to meet my teaching aims which were to increase their confidence in this particular type of reading exercise. The exercise was a gapped text, one where sentences are taken out of a text and students need to place them in the correct gap within the text. An extra sentence which does not need to be used is also provided.

Referring back to our class presentation on adapting and supplementing materials I can say that my decision to ‘tweak’ this reading exercise relates to a lot of things mentioned in the picture of our mind map above. As for the reason why I decided to adapt this piece of material, it definitely had to do with increasing my students’ motivation. I’d done this exercise with my students quite a few times before my observation and most of the time they looked confused and demotivated. The fact that they became aware of specific reading strategies and discourse devices made it easier for them to notice them in the text, and therefore their results were almost perfect. I also remember one of my students saying at the end of the class: ‘I now feel that I’m getting better and better at this type of exercise’. That was the moment which made me feel that adapting had probably been the right decision.

As for ‘how’ I adapted the material: I found two different sources talking about the same topic (the history of Valentine’s Day), I selected the parts that were similar to each other and more relevant to the topic itself, and then added some linkers hoping that my students would notice them and choose the correct answer. Providing some extra discourse devices, seemed to help with ‘noticing’ the language and students were able to see how using particular reading strategies can help when answering comprehension questions.

As far as ‘when to adapt’ is concerned, I decided to do so after I’d realised my students’ need for it. It was an observation rather than a spontaneous decision. The next step was to plan how I could adapt the material to facilitate my students’ needs, and at the end of the class I asked them to provide feedback on the level of difficulty of the text as well as whether the reading strategies we’d discussed had helped. They all reported that it was neither the easiest nor the most difficult reading exercise they’d done and that the strategies were helpful. Finally, my tutor’s feedback was that the level of difficulty was appropriate for a B2 reading exercise and that the ‘explicit attention to the use of cohesive devices benefitted the whole class in their success in this practice’.

In a nutshell, I’d say I really enjoy adapting and supplementing materials and this example has taught me that we should adapt or supplement as a response to our students’ needs, not merely for the sake of it.

References

McGrath, I. (2013) Teaching Materials and the Roles of EFL/ESL Teachers: Practice and Theory. London: Bloomsbury.