Is there an association between Thoracic Outlet Syndrome and anatomical variation?

Blog by Steph Proffitt, MSc Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy student:

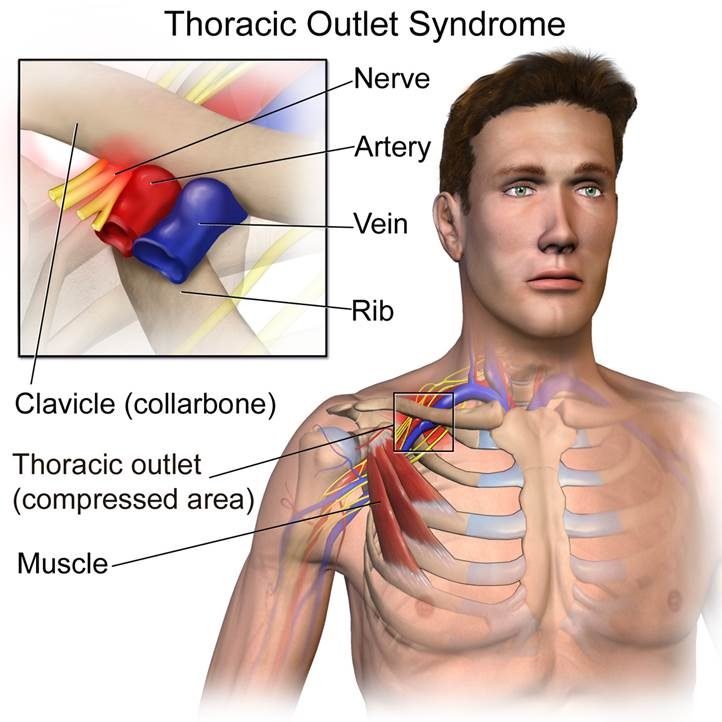

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is not a particular forte of mine and I can probably only count on one hand the number of times one of my colleagues has asked “could this person have TOS?” when they are confused by a patient presentation. I therefore took this opportunity to read some of the literature that has been published on what is renowned as being a controversial topic (Hooper et al 2012). Whilst reading about TOS, it was surprising to read numerous articles referring to anatomical variants such as cervical ribs and fibrous bands (see image) so heavily considered in the aetiology of this condition. What was also interesting, was the number of asymptomatic people who present with positive clinical tests for TOS, which made me question their validity.

Therefore, the first part of this blog will focus on whether there is an association between TOS and anatomical variants and the second blog will evaluate the clinical tests used when TOS is suspected and whether these tests are useful in clinical practice. As part of the blogging process at Brighton University (this blog was the assessment for one of my modules), our peers make comments on our blog which encourages further discussion and depth to the blog. I have included these questions and the responses as part of this post.

So, is there an association between TOS and anatomical variation?

Well, one of the first people to document findings from surgical procedures performed to alleviate alleged symptoms of TOS was Roos (1976). He felt that TOS was underdiagnosed and suggested large numbers of people without a clinical diagnosis experienced a generalised aching pain that radiated from the scapular down the inner aspect of the arm along the ulnar nerve distribution. During one of his studies, he discovered seven types of very distinct anomalous fibrous or muscular bands in 100% of 241 surgical procedures conducted for TOS. He also evaluated 29 cadavers with “known” TOS and reported different types of these same fibrous bands again, in 100% of the cadavers he reviewed.

The bands originate and insert between different areas of either cervical or thoracic ribs, or are formed by small muscular bands attaching between the scalenes. Arrow: A typical example of a fibrous band (Type 3) with attachments on the first rib (Image taken from Roos 1976, Congenital anomalies associated with Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, The American Journal of Surgery.)

The problem with Roos (1976) work, was that it was purely observational. He believed the anomalies found were directly related to their symptoms and could be causing mechanical irritation or even compression to the brachial plexus and estimated that with correct surgical resection, relief of symptoms could be found in 90% of cases. Unfortunately, it is difficult to eliminate bias in an observational study, especially when evaluating his own work. He also fails to demonstrate how he differentiated between other potential causes for the neurological symptoms and there is no mention of any pre or post-surgical outcome measure or reference to any long term follow up. Considering his patients had been involved in lengthy conservative management approaches, how can we determine how much of their alleged symptom resolution wasn’t due to placebo? After all, there is evidence to suggest, the non-specific effects from surgery are large, particularly in pain related conditions (Jonas et al 2015).

Further surgical work, evaluating anatomical variation has been conducted by Sanders & Hammond (2002), who documented findings from 65 surgical procedures performed to resect cervical or anomalous first ribs out of 1000 patients with a supposed diagnosis of TOS over a 28-year period. It is worth noting the remaining 935 patients had an apparent diagnosis of TOS, but did not have cervical or anomalous ribs. One limitation of this study is the wide variation in clinical symptoms described by the subjects and also the lack of consideration of other potential diagnoses. There was also a lack of standardisation within their physical examination procedure with all subjects. The failure rate following the surgical procedures ranged from 24% – 41%; the authors directly associated this to whether they resected a cervical rib alone or a cervical rib as well as the first rib, the latter being more effective…… a simple yet questionable reason. Interestingly, 4 operations were undertaken due to a work-related accident and 75% of these failed (3/4), when a cervical rib alone was resected; if a first rib was also resected the failure rate was 25% (2/8). Despite the high failure rate, the author did not use a recognised outcome measure evaluating the psychological status of these individuals.

An alternative study by Demondion et al (2003) attempted to make anatomical comparisons between a symptomatic group (n=54) versus an asymptomatic control group (n=35). The symptomatic group were included if they had two out of six positive clinical provocation tests and were then categorised into one of three groups; arterial, neurologic or neuroarterial, depending on clinical signs and symptoms described. Apparently, there were no “cervical signs” reported that could alternatively explain their symptoms (although didn’t elaborate on how they determined this). So, both groups were all examined in a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner in two positions; both arms in neutral and again with their arms positioned at 130° of abduction combined with external rotation. Two experienced radiologists evaluated the images and were blinded to which group they were evaluating.

This is what they found: –

- the costoclavicular space demonstrated a significant decrease p = <0.001 in the minimum space available once the arms were elevated in the symptomatic group compared to the control group.

- The thickness of the subclavius muscle was significantly greater in the symptomatic group when the arms were in neutral or elevated p= <0.001.

- The distance between the border of the pectoralis minor muscle and axillary posterior lining at the passage of the axillary vessels was again significantly reduced in the symptomatic group when arms were elevated compared to the control group p=<0.001.

There were significant anatomical variations between those with and without the condition. So, what does this mean? Well firstly, the clinical tests used in the inclusion were not described, therefore it is impossible to understand how a positive test was determined at the outset; additionally, there was no mention of whether the provocation tests used were even valid?!

Secondly, they did not explain the relevance of why they positioned the arm in 130° of abduction combined with external rotation. They did not mention whether this was linked to the positive clinical test position or even if this position provoked any symptoms? Thirdly, they failed to describe how (if at all) they differentiated clinical symptoms with alternative pathologies that may have been present. In essence, the findings don’t mean a great deal in the context of TOS, because we don’t know if the symptomatic group even had TOS!

I therefore decided to look at articles which may highlight these anatomical variants incidentally. I found numerous studies that have identified cervical ribs on either routine chest imaging, Computerised tomography (CT) or Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Brewin, Hill & Ellis 2009, Viertel et al 2012 & Waldren et al 2013). The largest study evaluated 2,083 cervical MRI scans to determine the prevalence of cervical ribs. They found cervical ribs in 1.2% (25) of cases; 12 of those were deemed to have brachial plexus or subclavian artery compression as a result of the cervical rib, but only one individual case was found to have the corresponding clinical symptoms on the side the cervical rib was found (Waldren et al 2013).

Generally, these findings are consistent with the current train of thought on people with low back pain. A really useful study that I often refer to in clinical practice is the study by Brinjikji (2015), which highlights high levels of pathoanatomical findings that are often seen in asymptomatic individuals. As clinician’s, more of our focus has shifted away from the biomedical perspective, to incorporate more of a biopsychosocial approach to health care (Sanders et al 2013) which is a prevalent topic in research. For example, a recent systematic review has looked at whether people who have a tendinopathy have sub optimal outcomes if psychological variables are present (Mallows et al 2016). It is also known that fear, anxiety and psychological trauma is associated with pain and can contribute to persistent pain (Lumley et al 2011). This evidence of psychosocial contributions and high rates of pathoanatomical findings, seems to have been forgotten in the case of TOS.

So, going back to the original question. Is anatomical variation associated with TOS?

From looking at the literature and taking into consideration more of a modern perspective on how we can’t always make direct correlations between images and symptoms. My view, is that anatomical variation can be present in people who are asymptomatic and some of the studies highlighted illustrate symptom reoccurrence despite surgery to remove anomalous ribs (Sanders & Hammond 2002). It is also essential that we use a person-centred approach within clinical practice and try to place equal value on all aspects of the individual in front of us, including their social, emotional, spiritual, mental and physical needs (Stuart 2017). With this in mind, I don’t believe an association can be strictly made between anatomical variation and TOS.

Blog 1: Question 1

“Very interesting blog Steph, I do however have a question or two that I hope you could shed some light on and also to get your thoughts of how it may effect your clinical practice. In the Demondion 2003 study, did they find any extra ribs? This study looked into more issues that we (as physios) could treat and effect. Based on the evidence would you suggest that in your opinion and clinical practice, surgery is not really an effective option given the risks of surgery, and the poor failure rate, of up to 41%.? (that’s flip a coin territory). Also, the first two studies don’t look at control subjects so is the change a direct cause of their symptoms? I agree with your final paragraph regarding lower back pain. Also, many patients will be born with this extra rib so why do symptoms start when they do and not at birth then? More posture related? Change in muscle imbalance? Etc? Things as a physio we can affect. So, would you send your TOS patients to an orthopaedic consultant?”

Hi Alex, thank you for raising some interesting points that would definitely be worth expanding upon.

In the study by Demondion (2003) they obtained XRAY’s of 37 out of the 54 “patient” group and found cervical ribs in a total of 5 cases, which were all confirmed on MRI scan. They state that in 4 patients, the MRI scan highlighted subclavian artery compression which was caused by fibrous bands, 2 of which were associated with cervical ribs and one that was linked to an elongated transverse process. However, the presence of the fibrous bands were only confirmed during surgery in 2 of the cases. They fail to mention the outcome of these patients within the study.

I must mention that the individuals involved in the “patient” group were deemed symptomatic of TOS based on whether they had 2 positive clinical tests, they do not state whether these “patients” had symptoms prior to enrolling in the study. More on this topic in the next blog!

I suppose there are risks of failure with any surgical procedure, however the study by Sanders & Hammond (2002), highlight interesting findings with regards to failure rates in those who had TOS symptoms as a result of work related injuries; in this group, the failure rate was higher than those who had a spontaneous onset of symptoms (42% vs 18%). This article by Horsley (2011) highlights the multitude of factors that can contribute to chronicity following a work-related injury; such as the individuals and the clinician’s attitudes and beliefs about the injury, litigation processes and also the supportiveness of the work place. These psychological and social aspects play a greater part than the medical issue itself or the persons physical ability to carry out their role at work. I suppose my point was to highlight that there are other factors involved in surgical failures, it’s not just about how many ribs were removed.

With regards to the first 2 studies that did not use control groups, again, I still feel it is difficult to say that the results were purely due to the physical procedure without taking into consideration other factors. To give you a few examples, the study I mentioned in the blog was by Jonas et al (2015), they conducted a systematic review of literature that had conducted surgery with a sham procedure for comparison; they found the nonspecific / placebo effects of painful conditions such as back pain and arthritis accounted for up to 78% of the overall improvement. Similarly, it has been found that there are a number of psychosocial factors that affect the outcome of those that have an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, such as their level of internal health locus of control, fear of re injury and also their behaviour towards their rehabilitation programme; some of the studies involved in this systematic review involved surgical ACL repairs (Wierike et al 2013).

In response to your question regarding the cervical ribs, I completely agree that it is more than likely (but we don’t know for certain) that these individuals were born with these ribs so to say their symptoms are purely related to this structural anomaly doesn’t really make sense scientifically, because surely, they would have had symptoms earlier. However, we don’t know anything about these individuals, what their hobbies are or what occupation they have, their feelings towards their symptoms and whether they believe they need surgery to help with the resolution of their symptoms. It is therefore difficult to answer the question relating to posture or muscular imbalance without this information or at least assessing the individual functionally. I have learnt the hard way over the years that treating the person is much more successful than treating their “condition”.

I can only reiterate literature from the likes of Brinjikji (2015) highlighting the presence of degenerative changes seen in the lumbar spine in asymptomatic’s, Girish et al (2011) and their findings relating to shoulder abnormalities found on ultrasound in an asymptomatic group and also Emerson et al (2010) with poor correlations found between structural changes in the achillies tendon and symptoms in elite gymnasts. So, to answer your question regarding whether I would send anyone I suspect to have TOS to an Orthopaedic consultant, I don’t think I would.

Blog 1: Question 2

“Very interesting blog on a difficult subject. I was just wondering if Roo attributes the symptoms just to the presence of the fibrous bands (does he mention cervical ribs etc in any other studies) and is there any reference to the presence of these in normal anatomical texts?

Also, Demondion categorises patients into three types according to the nature of symptoms. Could you expand a little on the theory of the presenting symptoms which have attributed to being TOS?”

Hi Nicky, thank you for reading my blog and for your questions.

I believe I have touched on the first question within the blog relating to the presence of cervical ribs in asymptomatic’s and also Roo’s views on the underlying aetiology, being strictly related to the presence of congenital abnormalities associated with fibrous bands or cervical ribs. I will therefore focus on the second part of your question.

In the study by Demondion et al (2003) they classified the “patient” group based on their signs and symptoms into 1 of 3 groups: –

- Arterial: describing symptoms such as (ischemia, pallor, coolness, fatigability, pain, muscle cramp, pulselessness.

- Neurologic: paraesthesia, numbness, tingling, progressive weakness, loss of dexterity or pain.

- Neuroarterial: being a combination of arterial and neurologic symptoms.

Essentially, the theory behind the term TOS, revolves around compression of the neurovascular structures within the thoracic outlet which ultimately creates arterial, vascular or neurogenic symptoms. The compression can occur at different areas, such as the interscalene triangle, the costoclavicular or the pectoralis minor space (Illig et al 2016).

Ferrante (2012) goes into depth about the different types of TOS that I have summarised below.

Arterial: A rare type but usually involves compression of the subclavian artery between the anterior scalene and a bony anomaly, most commonly a cervical rib. This compression, leads to turbulent blood flow and an aneurysm is formed, thus reducing blood flow distally. Signs such as an absent or reduced distal pulse, paleness of the skin, coolness to touch and reduced capillary refill are typically seen in those affected. Because this is normally a unilateral issue, these signs should be easily identified from their non-affected side.

Venous: Again, a rare type and involves a thrombosis of the subclavian vein due to a compressive force, either the first rib or a hypertrophied scalene or subclavius tendon. Those affected will have symptoms that come on after exertion of the limb, with swelling, cyanosis and pain.

True Neurologic: Ferrante’s (2012) review reports this is a rare type and affects the peripheral nervous system, it is related to fibrous bands that extend from the thoracic spine to the cervical spine or the presence of a cervical rib or an elongated transverse process. Due to the course of the brachial plexus, the lower trunks seem to become the most irritated, as the fibrous bands come into contact with the brachial plexus it causes a stretch to occur on the C8/T1 trunks, hence affecting both myotomal and dermatomal distribution. The motor symptoms are more pronounced than the sensory symptoms, with weakness, wastage and an inability to use the hand and problems with dexterity being most reported.

Non-Specific TOS: This type is apparently most commonly seen in females, with symptoms being bilateral. There are different mechanisms proposed, such as congenital abnormalities that have been previously mentioned, trauma, such a whiplash injuries or repetitive strain that may cause scarring to the scalenes or the brachial plexus itself or muscular imbalances. The third mechanism being postural dysfunctions that can cause adaptive shortening and tightening to the muscles around the thoracic outlet that subsequently causes pain. There is controversy surrounding the signs and symptoms of this classification, but sensory symptoms appear to be the most reported in more than 90% of those affected, predominantly reporting pain along their upper limbs within the distribution of C5/6 or C8/T1.

More up to date documentation by (Illig et al 2016) has suggested that the use of “Non-specific”, “true”, “disputed”, “mixed” or “vascular” classifications should be avoided as they can cause confusion. His work advises that there should be only three classifications, venous, arterial or neurogenic.

I appreciate that this is a very biomedical perspective on the topic, but this is what the literature focuses on. I feel Illig et al (2016) work offers a more rounded approach to TOS and I suppose it is also worth noting that there is evidence to suggest that there can be peripheral drivers to chronic pain conditions, such as phantom limb pain (Vaso et al 2014). Although we have moved away from looking at scans and making assumptions on the cause of the symptoms (See response to Alex), there may still be an argument to address this peripheral driver i.e. a cervical rib / fibrous band.

Hand clinic January 6, 2023 - 4:15 pm

You make so many great points here that I read your article a couple of times. Your views are in accordance with my own for the most part. This is great content for your readers.

https://hand-microsurgery.com/