Learning about theoretical discourse has been a large part of my education at the University of Brighton, sadly a path not widely shared by my peers. Often, I am asked, quite bluntly, what is the point of literary theory. And up until now, the chagrin of not being able to give a fully coherent answer has left me appearing to reinforce the ‘plaisir’ of textual consumption; as opposed to advocating ‘active reading’ and the resulting ‘jouissance’, of which theoretical study is integral.[1]

But, now I have my most coherent answer yet, a finite way of explaining the primacy of ‘theory’ in the study of any given text. I introduce to you Terry Gilliam’s cult masterpiece Brazil (1985), a raw and hilarious satirical ‘text’ depicting a dystopian future Britain constrained by a hegemony centred around bureaucratic ‘red tape’ gone awry. For those of you unfamiliar with the piece, the film follows the ineffectual Sam Lowry (Jonathon Pryce) and his ludicrous quest to find the girl of his dreams (very literally), whilst attempting to evade the increasing threat of a broken air-conditioning unit that resides in his flat.

On the surface the film and its message seem very straightforward; an open attack on a totalitarian modern age, mixed with swipes at bourgeoisie ideologies, all placed under the umbrella of absurd hyper-bureaucratic nonsense. However, there are aspects of the film that are enigmatic and ambiguous at first glance, the cultural signification of Michael Palin’s ‘Torture Mask’ exemplifies such a discrepancy in meaning, and still alludes me to this day.

Yet all hope is not lost. It is with the application of theoretical discourse that one can begin to ‘unpack’ the deeper meanings within the architecture of Gilliam’s film, giving meaning and purpose to the more illusive undercurrents of the text. Most importantly, before this essay begins, I am not arguing that everything in Gilliam’s Brazil is to be placed under the microscope; I personally believe that Palin’s ‘Torture Mask’ (ironically) is most effective as a talismanic symbol of Brechtian alienation, one of which begs the engagement of the audience’s critical faculties because of its uncanny presence. However, many of the films more poignant swipes at modern culture can be unlocked through the careful application of literary, philosophical and cultural theory.

To begin, let’s take protagonist Sam Lowry’s reluctant dinner with his pseudo-debutante mother, Mrs Ida Lowry (played by Katherine Helmond). The most striking joke in this whole scene is the food that each of the members of the table order. When it arrives, their ‘orders’ are nothing more than amorphous coloured lumps accompanied by an exquisite picture of the ‘real’ food each person ordered from the menu. As it stands this is a simple joke of misdirection; they have ordered food; they have not received what they thought they would receive; it’s so funny how weird the future is…

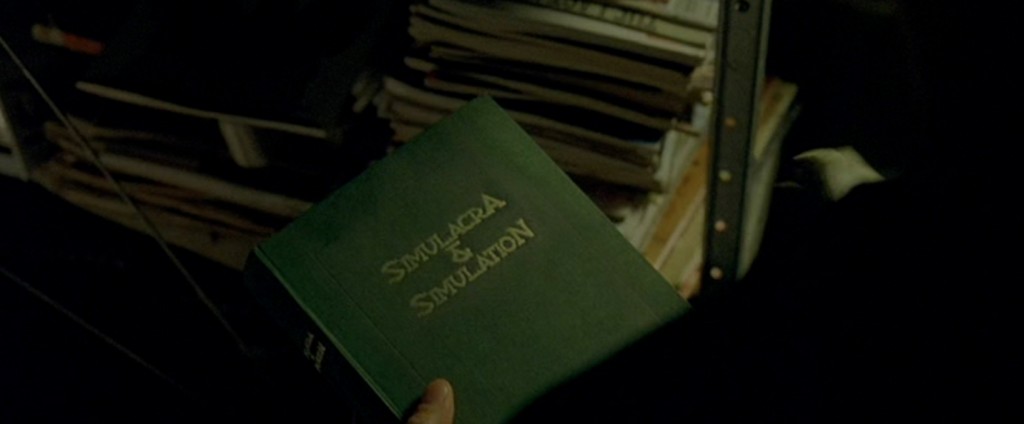

Now, when considering Jean Baudrillard’s theory of ‘hyperreality’, in his work The Vital Illusion and The Illusion Of The End the innocuous food blobs take on a much more sinister and satirical meaning.[2] In Brazil’s future dystopian society, the bourgeoisie culture ‘no longer [has] any critical or speculative distance between the real and the rational’, their food is an example of a hyperreality. The blobs ‘abolish the real’ food that has been ordered, ‘not by violent distinction’ but by ‘the strength of the model’ i.e. the picture, the perfect example, of which, can be imbued with the recipient’s emotional resonance. This image or ‘referent’ has penetrated the reality of the culture, becoming an adequate substitute for food and thus we are left with a meal, stripped of its impetus, being and reality.[3] This analysis provides a much darker and more biting satirical commentary (much more in keeping with the tone of the film). Through such an analysis, we are no longer bamboozled by the manifestation of a very queer futuristic looking meal, instead we are enlightened to a much more subtle derisive swipe at bourgeoisie cultural values and its practices.

Next, an analysis of the heroic and hilarious Archibald Tuttle (played by Robert De Niro), a rogue plumber hell-bent on making the world a saner place in the face of Central Services, because, after all, ‘We’re all in this together’. Tuttle’s minor role in the film serves, at first, to reflect how mad a dystopian capitalist Britain has become. The extreme lengths that Tuttle must go to, zip lining around high-rise industrial housing blocks for fear of death, for being an independent plumber convey the capricious behaviours of this fictitious Britain’s institutional state apparatus.

However, the madness of this fictional Britain’s authoritarian ideology runs much deeper than merely Tuttle’s escapades. By drawing on the influential critic Raymond Williams, in his work, Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory, we can see how the character of Tuttle is symptomatic of a proposed future capitalist society that has lost any ability to distinguish between ‘oppositional’ and ‘alternative’ sub-cultures. As a result, the ‘dominant mode’ of the British state is to extirpate all forms of emergent and residual cultures, be they opposing or not.[4] Moreover, this notion presents the argument that capitalism is unstable and detrimental to humanity’s freedom.

Let’s consider the hyper-capitalist Britain that is the background to Brazil to be the ‘dominant mode’ of society. We might then consider Archibald Tuttle to be an example of a ‘residual mode’ of practice, an out-dated idea of capitalist culture (by Brazil’s premonitory standards) that allows for competition to provide the best service for the consumer, i.e. the best and most reliable plumber at the most competitive rate. In its current state, this version of Britain has ‘incorporated’ all competitive plumbing outlets into the dominant mode via the Central Services, in an attempt to maintain the maximum profit. This is where the role of Archibald Tuttle in relation to his society becomes misleading. If Tuttle were gaining any monetary profit, and thus impinging on the dominant mode, he would be considered oppositional and ripe for eradication. However, Tuttle’s reasons for going rogue are put down to simple socialist empathy, ‘We’re all in this together’, and in conjunction a hatred of bureaucracy depicted by the collectively dreaded ‘form 27B/6’. In actuality, Tuttle poses no real threat to the infrastructure of the dominant mode, as Williams states, ‘in capitalist practice, if the thing is not making a profit, or if it is not being widely circulated it can be for some time overlooked’; he is nothing more than a freelance plumber picking up the slack for Central Services, a residual and alternative mode in society.[5] So why is he a person of interest to the Ministry of Information? Well, the very fact that Tuttle has a gun in his tool kit, and works under the cover of darkness, is illustrative of an authoritarian state that is so greedy and power mad that any alternative mode of practiced living to the dominant mode is unacceptable. In Brazil, there is no longer incorporation, only extermination. Thus, Tuttle’s character foregrounds how Britain in this proposed future society has lost all sense of humanity and cultural co-existence because of extreme capitalist endeavour. We might then read that, in the eyes of the text, capitalism can only lead to the eventuality of totalitarianism. This idea is exemplified in the opening of the film when, due to an insect related error, the cobbler Archibald Buttle (as opposed to Tuttle) is removed from his home and sentenced to death by the Ministry of Information.

By extrapolating on the film’s minor characters in conjunction with cultural philosophy, the role of Tuttle and Buttle have become expository in a wider social reading of the film. However, without the use of Raymond Williams’ discourse Tuttle becomes nothing more than a helpful plumber whose primary aim is to fight authoritarian bureaucracy, and Buttle as simply a casualty of that bureaucracy in action. Without theory, Brazil’s wider intimations remain closed off to its audience.

To conclude, I hope this essay has shown that ‘theory’, in its many varied forms, is of the gravest importance. By applying certain theoretical discourses to specific and often enigmatic aspects of a text, one can elucidate meaning more readily; lumps of ‘future food’ reveal themselves to be very intelligent and witty satire; the analysis of minor characters serve to single-handedly illuminate the entire architecture of their text. Now when people ask me, ‘what is the point of theory again?’ I can answer simply, that it makes understanding a text so much ‘easier’. And, wouldn’t it be nice if the world was a little ‘easier’ or ‘clearer’, I mean, ‘We’re all in this together’, aren’t we?

[1] Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text (New York: Hill & Wang 1980)

[2] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, in Literary Theory: An Anthology, ed. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan (Blackwell Publishing ltd 2004), pp. 365 -378

[3] Malpass Simon, The Postmodern (Routledge 2005) p. 94-95

[4] Raymond Williams, Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory, in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism: An Anthology, ed. Vincent B. Leitch (London: Norton 2010), pp. 1432 -1433

[5] ibid. p. 1433