This blog post has been abridged from a longer, imaginary conversation between Naomi Salaman and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven(1874-1927), the mother of conceptual art. (Thanks to heavenhelpusdotorg and Siri Hustvedt).

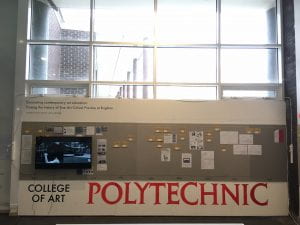

Excavating Contemporary Art Education, Tracing the history of Fine Art Critical Practice.

University of Brighton 4-29th April 2019

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven : So remind me how this exhibition came about….

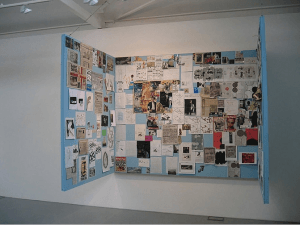

Naomi Salaman… we were talking with Ben Roberts and he offered us the Atrium Gallery for our archive project in April 2019 when the Association for Art History Annual Conference was happening. We were involved in chairing one of the AAH day sessions ‘Art Education; the making of alternatives’ – and so instead of offering a paper for the conference, Sue Breakell and myself planned a display of our work in progress. As you know the Fine Art Critical Practice archive is really just a few fragments, and an open invitation – there are virtually no institutional records to be found dating before the late 1990’s. So my part of the exhibition was visualising a space for the course, understanding it over time as a situation where certain kinds of art practices were talked about and taken seriously. We’ve been putting together a special issue of the Journal of Visual Arts Practice, entirely as a collecting and reflecting processs of archiving, of gathering accounts and records on and about the course.

EvFL : and how did the design take shape?

NS: Ben led us to the Atrium Gallery and the walls became present in my head as blocks to play with, long before a design emerged. The whole of the first semester this year, I’d walk through the space on the way to the cafe, or up to the studios and look at the walls and wonder how to map the time of the course onto it.

Formally the space did suggest solutions – the left hand, eastern wall is longer and lower than the southern wall, and their respective shapes, read from left to right became representative of the two institutional forms that evolved containing the Department of Fine Art in which the FACP course sits. You could say there are three institutional forms if you include the College of Art, which preceded the Polytechnic, which then became the University. But the early days of the FACP course were in 1971 – by which time the College had become the Faculty of Art and Design in the newly merged Polytechnic. So in my head the eastern wall became the Polytechnic and the southern wall became the University. Just like naming a child, the walls became their name. The southern wall is almost square and rises to nearly 5 meters, its difference from the eastern wall became the thinking about the shapes of these two institutions. I could imagine the Polytechnic made of lego, a low slung functional plant made of a range of connected buildings, like a farm or a factory, whereas the University is just so much more top down, and seems to want to unify and iron out difference, and be ‘one’ thing. Beyond this idea of what the institution is or was like, the changes to education funding have completely transformed the ground on which higher education takes place in this country. The escalating student debt that I could imagine rising up the University wall was a line just waiting to be drawn – it goes along and then up and up across the blankness. It’s a bleak representation of what is, in actual fact, a huge risk that the government has taken with the institutions and provision of HE in this country. And a massive burden on young people.

EvFL : is it just a coincidence that the gallery walls and the sociological and art historical configurations you were mapping have such a neat fit?

NS: Well it is hard for me to answer that honestly and appear completely sane. But the coincidences are real and do indicate the fault lines in the strata. The site where we are exhibiting and the site of the history we are mapping, are contiguous. You know how we used to repeat that mantra ‘the map is not the territory’, well, here we have the exhibition space that is also the site of the excavation, here the map really is the territory..… it was actually quite uncanny how it unfolded.

Once we’d decided to affix pin board along the walls to represent the continuous running of the course across time and across these changes of institutional and socio – economic formation, we realised that the screws that secured the boards to the wall also offered up the wall in regular chunks, like a verse or regular metre, every two feet actually, that’s just because the boards are eight feet long. The running length of the two walls, divided by the spacing of the screws made for exactly seventeen units or divisions. We decided that three years would make a good unit for our timeline because a few years in particular were key – 1968 for instance and 1971, both important for our course history. What turned out to be another close fit was that the sequence of dates, in three year jumps from 1968-2016 made seventeen dates which Emma and Naz designed and made up as rubber stamps. This number of stamps exactly covered the number of divisions made by the screws holding the notice boards in place. Had I been more of an architect or a designer I would have started with such a calculation. But instead the maths became present in the space as we laid it out. The space is maths and yet it also has a history that came seeping through the walls.

EvFL : Do you think the building was speaking?

NS: Don’t be ridiculous. But I have to say, stamping that date, 1962, right onto the wall to the left of the pin boards next to the cafe was extremely satisfying. 1962 was the year that saw the first part of the new building open in Grand Parade that we still occupy; and it was the date Brighton was awarded the new Diploma in Art and Design for its Fine Art qualification; and the year that mandatory grants were available from the government to cover student fees and maintenance.

These three aspects of the fine art provision at Brighton underpin and shaped our history. The building contained it and gave it form. And that is why it’s so poignant that we have a rarely seen film work by John Hilliard From and To (1971), recently restored, digitised and acquired by Jenny Lund at Brighton and Hove Museum showing here – the windows above the exhibition wall below – are the very same windows seen in his film, shot on 16mm from outside in the quad, at the very beginning of course.

John Hilliard From and To (1971) digital still

John Hilliard is one artist clearly located as a course tutor, he played an instrumental role in the course and its offering until the mid 1980’s. Quite a bit of his work from that period was made around the building and the environs of the Downs with the participation of his students. You can see on the title cards to this film Camera – John Kippin – he was a student at Brighton Polytechnic at the time, and one of the student initiators of the studio in 1971 that became FACP.

EvFL : Well you say it’s ridiculous that the building is speaking, but don’t you think this exhibiotion sort of allows the building to speak? and hasn’t Sue Breakell said ‘the archive speaks’……. surely a building is a kind of archive?

NS: Well yes, and all sorts of unsayable things are held by buildings, so yes I guess you are right.

EvFL : So what are you trying to show about the course? Why an archive? Why do the boards look a bit empty?

NS: Well, one of the notable aspects of FACP is that it dates back to 1971 and it has been running continuously since then – that’s very unusual in itself for this kind of experimental fine art course. This makes it an interesting case study in post war art education, and we have been lucky to work with the Design Archives here to open an archive. Most other similar courses around the country have not lasted. I wanted to put some version of this on the wall which showed duration and at the same time logged the institutional and funding transformations. The duration is shown as an active investigation of its duration. So it’s a mapping of breaks, and changes, showing an impossible continuity. There is no continuity, while you could say there is a legacy, and a relatively stable provision. Sue is more involved with holding the archive materials and she organised the vitrine of fragments, which will be of interest to researchers, much of which has come from Mick Hartney, and she has written more about this for the journal. But I have to say both of us have been surprised by the lack of response from women artists and those who were students on the course, so far. Most of the old timers we speak to can hardly keep a straight face when we ask them to write about how they remember the course. Certainly the more Sue and I work on the putative archive of the course the more apparent it becomes that there are no women’s voices from before 2000 as yet recorded – it is difficult to trace or map any female experience of being on the course or teaching on it until really fairly recently. There are a number of contradictions here, firstly that the course is not what it was because the socio-economic conditions of being a student or young person have been so radically transformed, and contemporary art has moved on, or become more generic. The early days of the course seem progressive and free of much of the constrictions of the present, and yet it was white male dominated, most probably gender blind and also quite possibly disabling or actively disinterested in women’s potential as artists or students. That is not simply a speculation about the course, but rather a known phenomenon of the art world, and maybe especially of the conceptual art world. We could go much further back, but lets just talk about modern art – modern art as an institution is known to be ideologically and psychologically invested in tracing male footprints. And that is what Sue and I have done, unwittingly, in assembling records of the course so far. Sue has reflected on Mick Hartney’s collection of course material, (he used to run the course), and I’ve considered the work of John Hilliard and Rodger Cutforth, two artists known to be central to the course’s emergence. We have tried to find and involve women artists and students in the project, but so far we have not had any luck. The current cohorts and current academic staff are really interested and involved – but I’m beginning to wonder if actually the course was impossible for women in the 1970’s, 1980’s and 1990’s – though this is speculation and hear-say. There is so much we don’t know about what the course was, we don’t know much much more than we do know. This is why the course boards are a bit empty. On a practical level, the project has only just begun.

EvFL : That reminds me – you were talking a lot about these noticeboards, and their resonance.

NS: Yes I could really go on at length about the notice board, I’ve got quite a few lectures on it – as a form of practice that definitely informs what I do. I can now see a link with artists who are part of the history of the FACP course, such as Roger Cutforth and Tariq Alvi, and the practice of the noticeboard. It’s about a certain mode of working, sort of provisional, operational, investigative and sometimes diagrammatic. It’s about dematerialisation and practices of dematerialisation, while at the same time a noticeboard can be used by anyone – it’s a tool. And it’s an everyday tool intimately linked to flows of conversation, and to borrow from a Roger Cutforth pamphlet, it’s Non-Art. As a format for art it is based in the production of, or awareness of, conjunctures that are often contingent, that is located in time and space. The notice board cannot possibly hold all the information it refers to and it is not very easy to document or reproduce.

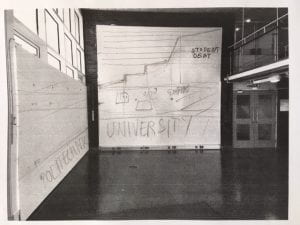

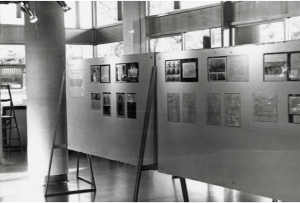

Dan Graham exhibition organised by Roger Cutforth 1971, Grand Parade foyer.

I was delighted to find these images of Cutforth’s mail art exhibitions he organised right here in this space – in 1971 with artists he’d been showing with in New York; Dan Graham, Robert Smithson, Ad Rhinehart and Mel Bochner. This was an impressive list of artists and practices that became part of the early informal teaching that went on in Experimental Studies.*

I came across Tariq Alvi’s work in the 1990’s, and did a gallery talk for his show at the Whitechapel in 2001. His show was a series of notice boards. At that time I wasn’t teaching on the FACP course, nor did I know that Tariq was a FACP graduate.

Tariq Alvi Whitechapel Gallery 2001

More recently, the format of the noticeboard has come up in the design for a FACP final degree show, from 2015 – Ive written more about that in the forthcoming JVAP volume. The cohort graduating in 2015 were the first year to experience the trippling of university fees, and as it happens, Lizzie How and Tilly Sleven – who began the FACP archive as a studio project in 2014, were graduates of 2015. So in a way staff and students become self conscious and began to investigate the course history around that time.

Wheely Good Artists, FACP degree show 2015

The idea of a noticeboard was raised even more recently by current FACP students just this year in a very different context – they were complaining they needed a place to see current information, and add their own events. If you look around the walls of this building, you will see all the notice boards are behind plexiglass, making them dead and official. Our current Head of School heard about this student disquiet and scrutinised decades of assumed fire regulations and then announced that actually we can have open notice boards with paper notices attached ad hoc the walls outside our studios. She has also re-introduced a staff room on the ground floor, and had it lined with pin board. This is all good news. It creates space for speaking to each other and for letting the building say something too.

EvFL : well good, glad to hear that, any chance you could organise one for us, from beyond the grave?

NS: I think Siri has done a pretty good job just recently, and there are other female scholars who have worked on your case, the question I guess, is when does a noticeboard register a tipping point?

Thanks to Louise Greggory for help installing all the boards, to Emma Deguara and Nazia Tamanna for their ideas and graphics input, Gill Scott for her help with the faculty history and the stats and to Chris Phelon for turning on the film in the gallery so many times.

* Maggie Finch Information Exchange; Robert Rooney and Roger Cutforth. ArtJournal 52 (2013)