From group exhibitions printing poems on textiles to programming for Mboka literary festival between Gambia and in UK, Akila Richards has worked in variety of settings as a community writing facilitator and poet.

After a residency at Creative Future, where she edited an anthology, delivered writing workshops and developed her own practice, Akila has most recently facilitated a group of fifteen writers living and working in Brighton for a large installation ‘Tenebrae: Lessons Learnt in Darkness’ at Brighton Festival 2021. She brought the writing community together during lockdown and spent four intense weeks (on Zoom) supporting them to put into words their feelings about the losses and strengths the last year has presented.

University of Brighton Creative Writing MA student Joseph Lee, also part of the Tenebrae project, met with Akila online to discuss how we can better make sense of the world through writing, opportunities to be part of a diverse writing community in Brighton and why ‘intense homework’ was the key to deliver high-quality work for the city’s internationally renowned arts festival.

Who is Akila Richards?

Akila Richards is a poet, spoken word artist and writer who engages with different genres. I have taken part in international cohorts of writers in the Caribbean and Europe, programmed literary festivals between UK and Gambia. I feel very fortunate after a lot of crafting and hard work that I can lend my skills in the arrival of new projects such as Tenebrae.

In terms of who I am and as a poet I believe in the community, in our community of writers, poets, be it emerging, be it published, be it famous, we are a particular community and I really believe in that.

For many writers, including myself, writing is a long journey. Maybe we start writing as a child, after a particular life event, trying out of different genres. For me I wrote as a child, then stopped.

I did other things, then wrote again and stopped. But there was something under the bed, in my words, in my sentences in my dreams, that was forming. They knocked louder and louder – there was this point when I could no longer ignore.

There was a callout for an anthology asking emerging writers asking to share a bit about them growing up and their writing journey. I remember taking my heart into my hand and I thought go for it! This was the beginning where I thought, ‘I love this’, it was the impact that it made on my life.

For many years now, when I write, the world makes sense to me. For all the chaos, destruction in the world, especially what we’ve experienced in the past year throughout COVID and lockdown – writing makes sense to me and puts things into perspective.

You have worked with a range of different communities and people – is there a stand out project you’ve been involved in?

I was invited to help program for the Mboka arts and culture festival between Gambia and UK. Africa as a continent has many countries and each country is unique as if you were to compare England with Sweden! Unique cultures, traditions and ways of being all connected the programming of this festival, working with International Artists from the US and in Gambia, we treated issues around the black diaspora. It really interested me how all these perspectives, discussions and types of creative genres came together.

What is your connection to Creative Writing at University of Brighton and more broadly Brighton as a place of creativity?

It took my a while to shift my gaze and perspective from London to Brighton. As a LGBTQ+ city, Brighton is an interesting and diverse place to live. Also, it’s not often seen and talked about bout its a very diverse town in terms of race. There are many different communities, older settled migrant communities, refugee communities and creative communities. The fresh blood from University of Brighton and Sussex University brings younger people into the city, in a small place this really adds an energy and vibrancy. The city has such a creative, open approach, I believe that every second person who lives in Brighton is an artist, one way or another!

Two Creative Writing MA students at Uni of Brighton are involved in a big project for Brighton Festival 2021 held at Theatre Royal on 22nd May, which you facilitated as a Community Writing Curator. Could you share a little more about what this project is and what it means to you?

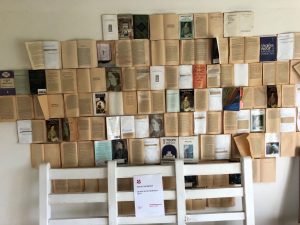

Tenebrae: Lesson learnt in Darkness was a vision over many years by Neil Bartlett. I’m honoured to have been brought into this project to give it my perspective, craft and experience – it means a lot to me. As Brighton Festival is an international festival, it usually means that not many local artists get the opportunity to be part of the project, even more so not many local BAME creatives get the opportunity to be part of it.

What I brought in was that locality, greater diversity, but not in a way of box-ticking but to be an integral part of our project. We are a mixed team, both on the mentoring side within the writers’ cohort in terms of age, background and experience. This differences are brought into perspective as the project launches now, it has made a huge impact – it is not your usual suspects. We took great care to treat every person with respect, no matter who they are, despite their status as a writer, respecting each person’s individual process.

How did you facilitate this huge project remotely during lockdown?

Managing this project on Zoom was not our preferred version. The first workshop session did not go to plan at all with lots of technical difficulties but we overcame that as the weeks went on. What I did know throughout is that we really had to benefit the writers, who had not really met each other before. We respected the differences of everyone involved but also similarities that the cohort were all writers and the priority was for people to write. We demanded a lot. We asked each writer to write new material in the space of four weeks, in constructive sessions and gave ‘intense homework’. We used a biblical text thousands of years old, used a piece of music that is 300 years old, through a verse structure and asked each writer to deliver their work.

Each writer took this so seriously. Some people did get stuck or didn’t understand where they were going next. There were clear indications that each writer gave their best and used many more hours than they anticipated. There was an appreciation that as a group of creatives we were going to provide something instrumental to the Brighton Festival during unusual times.

As a performance coach, how can writers develop confidence to share their work?

It is really important to remember writers are almost continuously ‘in process’.

This means that as a writer, you have to put the work in. Whether your write morning pages, work at night or write intensely for 24 hours non stop at the weekend.

When you are a writer or poet you need to bring in regularity to your craft and really respect it. Inspiration comes when you practice your craft and sit down write.

Read your work out loud. Ask yourself how the words feel in your mouth, do you get stuck on certain words, or do some lines flow? This is trying to tell you something, it tells you what works and where you need to hone it.

Print out your work and see it visually. When you have a collection of poetry or short stories you should see how how these narratives combine. Particularly in poetry the shape and form of how it looks and feels on the page is so important.

If you have a poem and don’t know what to do with it and you are getting stuck. Give it time and space, walk away and let it marinade on its own. Don’t look at it, just leave it alone. Whilst it is resting, it is ruminating in your brain. Then you can come back and you might have the answer.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to start their journey as a writer is struggling to connect with a writing community?

Writers need to take initiative. Certainly in Brighton there are so many writers groups and book clubs which have particular focusses on which community you associate with. Go to events, debates and network. When you become a writer there is a whole new world around you. As writing can be a solitary experience it is important to take part in workshops either online or in person. Make sure you submit your writing to competitions, submissions and commissions – being rejected helps you understand the process better when you do get accepted.

Writing Our Legacy raise the voices of the BAME writing community in East Sussex.

Creative Futures run workshops, masterclasses particularly for people who have experienced mental health issues.

New Writing South have a fantastic project where you can take part as an emerging writer using prompts.

Tickets for Tenebrae have now completely sold out, but you can find out more about the installation here on the Brighton Festival official website.

Article written by Joey Lee