From tailoring medical devices to individual bodily responses – to creative flexibility in shapes otherwise impossible to create, Lipson and Kurman (2013:14-15) argue the benefits of 3D printing lie within it’s ability for absolute precision and control. In the future Digital City, no longer will the manufacturing process have to allow for the ‘unpredictability and unruly nature of atoms’, but will be simply reduced to predictable code: 1 or 0 (Lipson & Kurman, 2013:14-15).

“3D printing offers us the promise of control over the physical world. 3D printing gives regular people powerful new tools of design and production. People with modest bank accounts will acquire the same design and manufacturing power that was once the private reserve of professional designers and big manufacturing companies”

(Lipson & Kurman, 2013:11).

A current example of Lipson and Kurman’s (2013) utopian arguments are made by Harvard Graduate Grace Choi when promoting her invention ‘MINK’, a 3D printer which prints make up from any home computer (http://www.businessinsider.com/mink-3d-prints-makeup-2014-5#!Kdzx1).[1] Choi (2014) emphasises that the power balance has shifted away from corporations into the hands of the consumer who now has the flexibility and control to create products or devices at home, for a fraction of the cost, without ‘intermediaries’ (Dini 2013) vastly speeding up the manufacturing process. Similarly, civil engineer Dini (2013) states his goal of 3D printing is to simplify and make affordable manufacturing processes, ensuring anyone can create, making the process accessible and democratic. Though we cannot predict 3D inventions that may become adopted and integrated into the Digital City of the future, we can speculate the possibilities for manufacturing control, precision, in turn empowering consumers and citizens, and encouraging new creativity and visions for future digital city products and services.

[1] We assume digital divides and illiteracies have been somehow ‘overcome’.

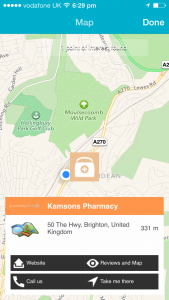

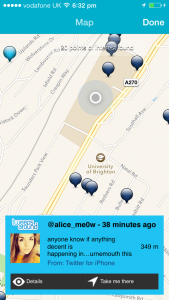

MINK – How Choi’s make-up printer works:

(All images: TechCrunch Disrupt)

“The 21st Century is going to be about bringing the virtual world into closer alignment with the physical one (…) 3D Technology will close the gulf that divides the virtual and physical worlds” (Lipson & Kurman 2013:13-14).

As experienced with the turn from analogue to digital, the unintended consequences that arise through technological innovation must also be considered. In response to Choi’s invention the Huffington Post argue ‘This Makeup Printer Could Destroy The Cosmetics Industry’ (Fieldman, 07/05/14). The possibilities granted by 3D printing further challenge the relationship between the physical and the digital; the amalgamation or dissolving of roles, skills, professions and expertise, cutting out the ‘intermediaries (Dini 2013) and making such technology accessible and affordable for all. This in turn will see a rise in user-generated content (‘pro-sumer’), a blurring of amateur and professional content and the arguable ‘de-valuing’ of such skills, expertise and industry (Hesmondhalgh & Barker 2011). As is the case for many of our creative industries such as film, music and publishing, with the increase in 3D printing innovations, might the same fate take hold of the manufacturing industries?

Extras:

Greg Petchkovsky is a sculpture experimenting with mixing digital sculpture with real objects, mixing the physical with the digital. http://vimeo.com/43442146

Bibliography

Dahue, R. 2013 ‘The Story of Enrico Dini – The Man Who Prints Houses | 3D Printing’, 3DPrinting.com (Available at: http://3dprinting.com/materials/sand-glue/the-story-of-enrico-dini-the-man-who-prints-houses/, Last Accessed 08/05/14).

Fieldman, Jamie. 07/05/14. ‘This Makeup Printer Could Destroy The Cosmetics Industry’. In Huffington Post: Style. (Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/05/07/makeup-printer-mink_n_5279546.html?ncid=fcbklnkushpmg00000063 , Last Accessed 08/05/14).

Hesmondhaigh, D & Barker, S. 2011. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries (Culture, Economy and the Social) Oxford: Routledge.

Lipson, H. & Kurman, M., 2013. Fabricated: the new world of 3D printing. Indianapolis: John Wile

Shontell, A. 06/05/14. ‘A Harvard Woman Figured Out How To 3D Print Makeup From Any Home Computer, And The Demo Is Mindblowing’ BusinessInsider.com. Includes a step by step guide of how to create your own makeup and use the printer (Accessible at:http://www.businessinsider.com/mink-3d-prints-makeup-2014-5#!Kdzx1, Last Accessed: 08/05/14)

Wainwright, O. 2013. ‘Will 3D-printed houses stand up as architecture?’ TheGuardian.com (Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/architecture-design-blog/2013/jan/22/first-3d-printed-house-janjaap-ruijssenaars, Last Accessed: 08/05/14).

Webb, M. And. Wake-Waker, J. 2014. The Man Who Prints Houses’ Documentary Film Trailer (Available At: http://www.themanwhoprintshouses.com/, Last Accessed: 08/05/2014).

Images

Screenshots from TechCrunch Disrupt. 2014.