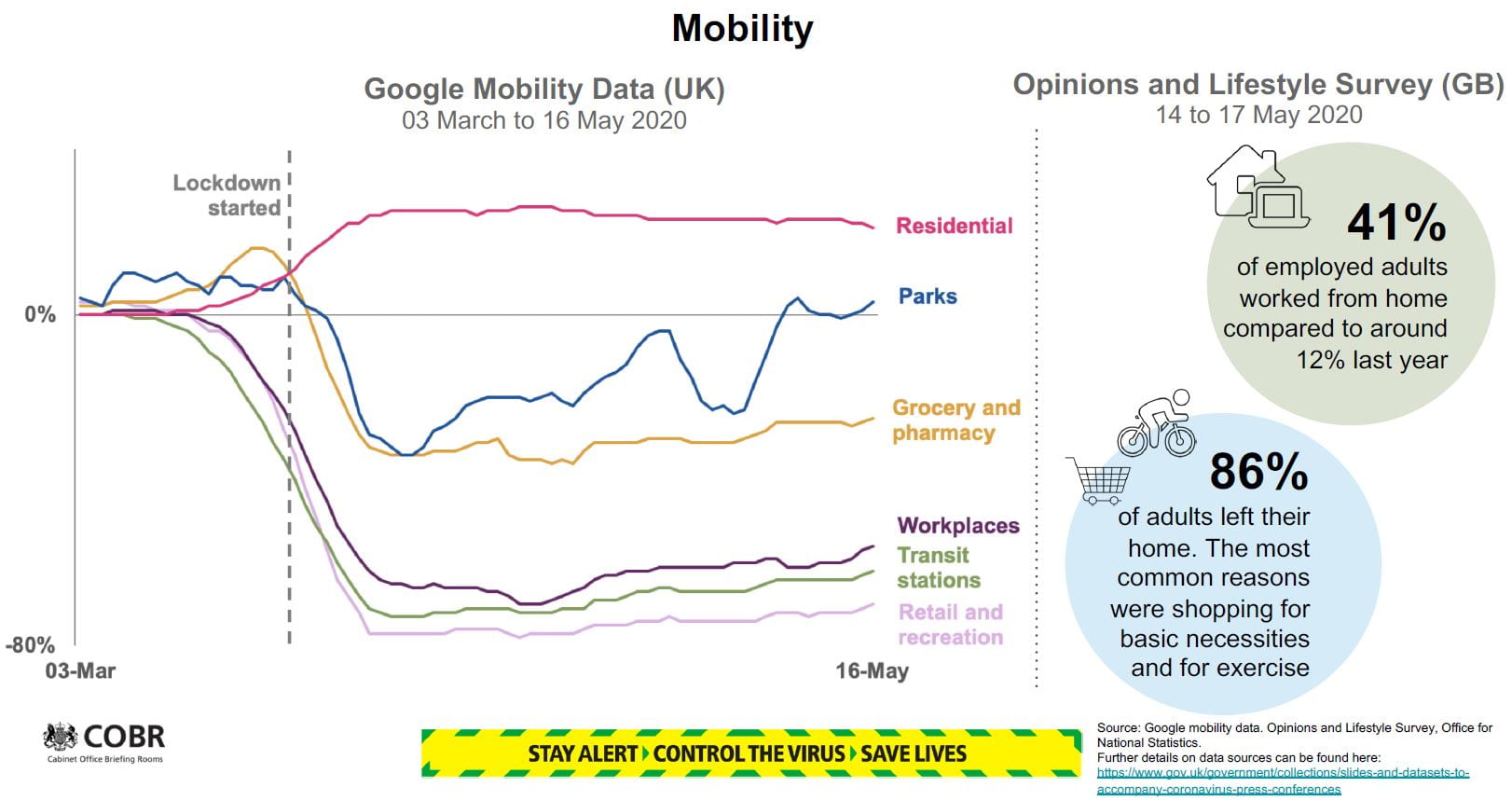

This week’s topic is mobile phone games, but in this blog post the usual case study of Pokemon Go has been replaced. At the time of writing this, in England, bumping into people in the street while being distracted playing Pokemon Go would be highly inappropriate. However our mobile phones are playing along in a huge collaborative endeavour. They are providing location-data which we see displayed, as a population, in televised government briefings (Figure 1) in a way that feels like a game score board. The rules of the game are to be seen (digitally, by providing location-data) in the right location ie residential is good and transit stations bad.

Figure 1: Mobility slide for UK Government briefing on 23 May 2020 (Gov.UK, 2020). Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/slides-and-datasets-to-accompany-coronavirus-press-conferences

The next step in the gamification of daily life is to move from population level surveillance to player level, through a contact-tracing app. Schechner and Strasburg (2020) provide a good explanation of current international debates on some governments’ centralised vs Google/Apple’s decentralised approaches, with the Bluetooth and location services options illustrated in a video-game style animation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Tracking apps explained using video game style animation (Schechner and Strasburg, 2020). Source: https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-google-start-to-win-over-europe-to-their-virus-tracking-technology-11589716800

Contact-tracing apps are based on mobile phones exchanging a key or token with other mobile phones within a certain proximity to each other. This transfer could be understood as a “co-surveillance mechanism” which de souza e Silva and Sutko (2009:15) refer to in the context of “mobile location-aware games” (Ibid, p2). The contact-tracing apps fits their definition of such games (pp. 3-4) as “(1) they use the city space as the game board, and (2) they use mobile devices as interfaces for game play”. They are “pervasive games” that “never stop and may intertwine with the player’s ordinary life”. They are a form of “Location-based mobile games (LBMGs)” whose “distinct characteristic […] is that they use mobile technologies with location awareness […] as the game interface”.

The question to end on is what is the role of the human player? The mobile devices are communicating with each other, but they need to be carried by their human users as they move through the urban space. The game’s purpose is to warn players when they may have been infected, and therefore need to isolate to break the virus’ chain of transmission. The reward for participating could be understood using Foth et al’s (2016:15-16) idea of “citizens at play” and their “civic capital” which they define as “a measure of a citizen’s actual and potential impact on contributing, participating and engaging in the civic surrounds”.

Contact-tracing app users are ‘citizens at play’.

References

Foth, M., Hudson-Smith, A., and Gifford, D. (2016). Smart cities, social capital, and citizens at play: A critique and a way forward. In Olleros, F. X. & Zhegu, M. (Eds.) Research Handbook on Digital Transformations. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, United Kingdom, pp. 203-221.

Gov.UK (2020). Slides, datasets and transcripts to accompany coronavirus press conferences. Coronavirus (COVID-19) | Guidance and support. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/slides-and-datasets-to-accompany-coronavirus-press-conferences

Schechner, S. and Strasburg. J. (2020). Apple, Google Start to Win Over Europe to Their Virus-Tracking Technology. Wall Street Journal (Online); New York, N.Y. Updated 20 May 2020. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-google-start-to-win-over-europe-to-their-virus-tracking-technology-11589716800

de Souza e Silva, A. and Sutko, D. M. (2009). Digital cityscapes: merging digital and urban playspaces. Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., New York. pp. 1-17.