Traditionally ‘public’ and ‘private’ spaces were defined through our daily routines between space and time; ‘home’, ‘work’, ‘leisure’ and ‘local’ and ‘global’ parameters (Silverstone et al 1994; Williams 1990). Our perception and construction of these different spheres is arguably achieved through our media consumption practices (Berry et al 2013; Habermas 1992). For example, the home was experienced as a ‘private’ sphere for ‘leisure’ and family time defined by your locality, with the working environment within the ‘public’, outside of the home (Berry et al 2013; Silverstone et al 1994); the very act of engaging, with television in the home was traditionally conceived as a family bonding and ‘leisure’ activity bringing “the experience of belonging to a nation into everyday life, enabling ‘the public’ to be experienced in ‘the private’” (Hollows 2008:107), and ensured citizens felt a part of the ‘imagined community’ of a nation (Habermas 1992). ‘A public’ refers more towards ‘an audience, gathering or following’ (Hannay 2005:26-32 in Berry et al 2013:3). The ‘public space’ or ‘sphere’ refers to intended action; “where private individuals come together to discuss and deliberate upon ‘public’ affairs and matters ‘in the public interest” (Berry et al 2013:3). [1] However, new structures and patterns of interaction are emerging from mobile and digital communications and networks (Wei 2013).

Now such familial communications and social activities can be displaced from the private ‘home’ and achieved whilst in the ‘public space’ through applications on a mobile device; an imagined community, family interactions achieved on the move within the city. “Wireless technology and the media that use have [… broken] down the boundaries of urban public space – as surely they do domestic space” (Berry et al 2013:8). Forlano understands this new ‘space’ as ‘hybrid’ (Forlano 2013), the ‘membrane’ between public and private (Groening 2010); the meditation of our daily routines and activities through digital modes, a reorganization of private experience within the public realm (de Souza e Silva 2006; Bull 2004).

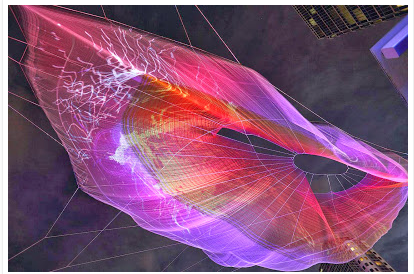

So how about connecting with strangers, other citizens in the public realm? An idea explored through a collaborative city art project in Vancouver ‘Unnumbered Sparks’ a collaboration between artist Janet Echelman and Google Creative Director Aaron Koblin, as part of TED’s 30th annual conference (2014).

“We all carry devices in our pockets that have the power to connect with people around the world, but rarely do we get a chance to use this incredible power to connect and create with the people standing next to us” (Ramasway 2014).

(Photo Ema Peter)

The interactive lighting sculpture is in fact a giant 300ft web browser with high-definition projectors. Visitors interact through their mobile device, using a mobile browser they select a colour and use their fingertips to trace paths using their device, projected onto the sculpture as beams of colour and light (Ramasway 2014). As Forlono argues “the appropriation and use of urban technologies have transformed the aesthetic, symbolic, and lived experience of cities in important ways” (Forlano 2013:1). This installation is a collaborative visitor and crowd controlled giant floating canvas, which anyone can create and contribute to in the public sphere, on their private device, collaborating with other citizens to create a stunning, visual experiment (http://googleblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/a-browser-that-paints-sky.html?m=1).

(Photo Ema Peter)

Such collaboration and the merging of private and public spheres calls for “a need for emergent notions of place, that specify the ways in which people, place and technology is interdependent, relational and mutually constituted” (Forlono 2013:2). This is a methodological challenge due to the “difficulty of defining the spatial and conceptual edges to research” due to the “logic of regional, national and temporal boundaries […being] undercut by mobile networks of connectivity” (Berry et al 2013:2-3). We need to develop a research approach, which develops mobile communications studies within other fields of research, for example anthropological, sociological and psychological studies, to enable a more holistic, and all encompassing approach (Licoppe 2013).

Bibliography

Bull. M. 2004. ‘To each their own bubble’: Mobile spaces of sound in the city’. In: Couldry N and McCarthy A (eds) Mediaspace: Place, Scale and Culture in a Media Age. New York: Routledge, 275–93.

De Souza e Silva, A, 2006, ‘From Cyber to Hybrid: Mobile Technologies as Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces’ In Space and Culture, Vol 9: 3 pp. 261-278.

Gergen, K. 2002. ‘Cell phone technology and the realm of absent presence’. In Katz, J. And. Aakhus. M. 2002. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press

Groening, S, 2010, ‘From ‘a box in the theater of the world’ to ‘the world as your living room’: cellular phones, television and mobile privatization’ in New Media Society Vol 12: 8, pp. 1330-1346.

Habermas. J. 1992. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Polity Press: Cambridge.

Hollows. J. 2008. Domestic Cultures. Maidenhead: Open University Press

Humphreys, L, 2013. ‘Mobile social media: Future challenges and opportunities’ in Mobile Media & Communication Vol 1: 20 pp. 20-25.

Humphreys, L. 2010. ’Mobile social networks and urban public space’, in New Media Society, Vol 12: 5 pp. 763–778.

Licoppe. C. 2013. ‘Merging mobile communication studies and urban research: Mobile locative media, ”onscreen encounters” and the reshaping of the interaction order in public places’. In Mobile Media & Communication Vol. 1 no. 1 122-128

Plant 2001. J. E. Katz. And. Aakhus. M. 2002. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press

Puro 2002. In J. E. Katz. And. Aakhus. M. 2002. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press

Ramasway, R. 17/3/14/. Google Creative Lab, ‘A Browser Which Paints the Sky’ (Available at: http://googleblog.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/a-browser-that-paints-sky.html?m=1, Last accessed: 13/5/14).

Silverstone. R. 1994. Television and Everyday Life London: Routledge,

Wei. R. 2013. ‘Mobile media: Coming of age with a big splash’, in Mobile Media & Communication Vol 1:50.

Williams. R. 1990. Television, Technology & Cultural Form, London: Routledge

Further Resources

Curran, J, Fenton, N. and Freedman, D. 2011. (eds) Misunderstanding the Internet. Routledge: London.

Humphreys, L. 2007. Mobile social networks and social practice: A case study of Dodgeball, In Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. Vol 13:1 pp. 341–360

[1] The traditional concept of the ‘public’ realm can be identified outside of the ‘private’ sphere, defined through professional and formal relations, the unfamiliar and perhaps characterized by the presence of strangers (Humphreys 2013). The family, the household, and informal relations can define what was traditionally conceived as the realm of ‘private’ life and the ‘private sphere’ (Habermas 1989), characterized by intimate and personal networks (Humphreys 2013).

[2] We use digital technologies, in particular mobile media to guide, inform, and entertain; this enables private spaces to be created within the ‘public’ (Gergen 2002; Plant 2001; Puro 200)