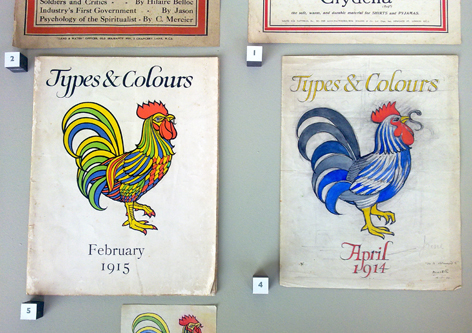

Max Gill conservation – day 2

Day two is over. We have managed to finish everything that was brought over to the studio at the end of last week – no mean feat of 26 objects in two days! Admittedly however, there were a fair few that only needed to be flattened but the whole experience was not for the faint-hearted. All of the pieces are looking absolutely fantastic! I took special joy in mechanically surface cleaning pieces that were especially dirty – it really feels like bringing a piece back to life and letting it breathe again!

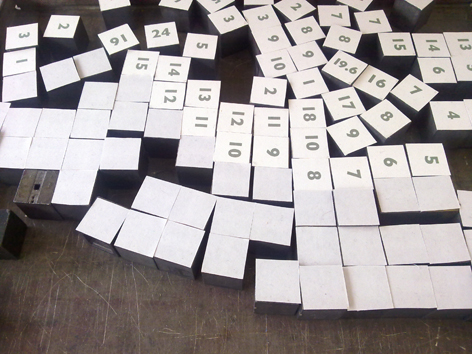

With conservation, while you need to do what you can in the time you have been given, ethics in every decision that is made need to be taken into careful consideration prior to treatments. All of the Gill pieces that needed flattening were able to take the flattening method of the heat press – this is where the combination of heat and pressure is used to relax the paper fibres. The heat press is used by placing an item between two sheets of silicone before pressing down. The silicone acts as a barrier and protects the paper from heating up too much. This method of flattening was chosen due to the time restrictions we were working under. A more traditional method is to humidify a piece, for which there are several methods for, and to flatten it under boards, placed between layers of blotter and tissue. These are generally left overnight to take effect after a few changes of blotters, depending on the humidification method used and the wetness of them.

One of the more challenging piece on day two was the ‘Atlantic Charter’ map, a pen and ink original from 1942 that I mentioned in an earlier blog entry. This has a selection of small pieces of paper attached to it that were coming loose and a dent running down the middle as the piece is constructed from two separate pieces of paper adhered together.

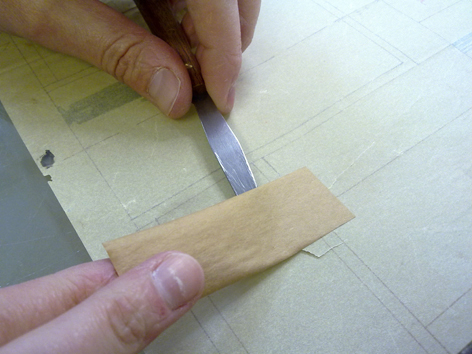

First thing to do was to remove the more loose pieces of paper on the piece. Roosevelt’s signature was coming loose from its edges and was very easy to remove by gently lifting it off the back with the aid of a spatula and bone folder. The same was done with the date piece, ‘1941’. The paper used on these two pieces was identical, slightly thicker and more sized compared to the paper on which the original artwork was created on and on which Churchill’s signature sits.

The adhesive used to adhere these pieces onto the artwork has left bad yellow-coloured staining behind. This kind of adhesive stain is very difficult to remove, and the best that could be done was to scrape off the residue from both the artwork paper and the reverse of the small pieces themselves. There was a fair layer of adhesive applied and below you can see a sample of the yellow residue that started to come off the piece on which the signature is on, slightly lessening the strength of the colour of the stain.

All of the loose pieces were adhered back to the original using 20% wheat starch paste. We needed to test the adhesion power on the loose papers before making the decision that this was good to be used. Wheat paste is very widely used in both book and paper conservation in differing strengths – in book conservation wheat starch can also be mixed with potato starch for added strength. In conservation when adhering loose pieces back onto originals or when repairing, the use of a proper adhesive is absolutely essential. It must have sufficient strength to maintain adhesion for an indefinite period of time, have no tendencies for discolouration and be easily reversible; meaning that it should be possible to remove a repair with minimum effort and damage to the object. Wheat and rice starch pastes has been tried and tested by time as Japanese mounters have used both of these for centuries. Methyl cellulose is another adhesive that can also be used in paper conservation.

On this Atlantic Charter map of Gill’s, Churchill’s original signature was on different type of paper and is still very well adhered to the backing paper by the original adhesive used. We did not remove this but simply adhered the slightly curling edges back to the paper by using wheat starch paste. After all of the pieces were secured back to their original positions, they were placed under weight and blotter to dry.

Some of the objects had to be cleaned using the sponge rather than rubber. This is due to the fact that the size used in some papers had a waxy surface to it, on which the rubber would not take to well at all. Gelatine has been widely used as a base for paper sizing in Europe, the use of it starting in Italy in the 13th century. A size can be spread onto the surface of the finished sheet of paper or added into the pulp during paper making processes.

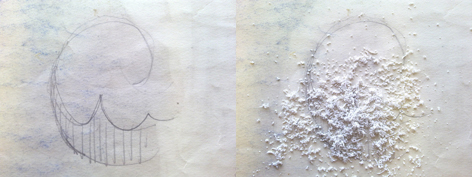

Where a Mars Staedler rubber can be used, it is usually cut to different sizes to be able to do different types of areas on a piece. As I have mentioned before, grated rubber is also widely used in mechanical surface cleaning in paper conservation. Below you can see a corner of one of the Max Gill pieces, where surface staining is very obvious, but where there are also original pencil lines along the margin of the paper. These pencil lines are obviously a part of the original artwork and special care needed to be taken to surface clean the corner from any unwanted stains but to not erase the pencil marks. As an alternative to grated rubber, a slice can be cut off a block to create a sharp edge to enable the use of a more solid piece to clean with that can reach right up to the pencil line. A thinner slice of rubber can also be used to gently brush over the pencil line to remove surface dirt.

As you can see from the image above, this corner of the ‘Cable and Wireless Great Circle’ map has the added, rather large ink stain in this particular corner. I imagined that perhaps Max knocked over an ink well while working on this piece!