Ethel Mairet, weaver

Ethel Mairet, née Partridge, was born in Barnstaple, North Devon in 1872. Having gained a Teachers’ Diploma in Pianoforte, she worked as a governess in London and Bonn. She travelled to Ceylon with her husband, Ananda Coomaraswamy, who she had married in 1902, studying, photographing and documenting processes of hand spinning, weaving and embroidery. Divorced in 1912, Ethel Coomaraswamy continued her work with weaving and dyeing techniques in rooms in her isolated cottage in North Devon. She made a second marriage, to Philippe Mairet, in 1913. Her treatise A Book on Vegetable Dyes was published in 1916, the same year in which Mairet moved to the village of Ditchling in East Sussex, setting up her influential workshop at ‘Gospels’, an Arts & Crafts style house that she had built. Her workshop nurtured many influential figures, including Marianne Straub, and its visitors in the 1920s included the potters Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada. Mairet published her book Handweaving Today, Traditions and Change in 1939, and was created the first female Royal Designer for Industry (RDI) in the same year. During the 1940s, she created a number of textile portfolios and informative booklets for schools and colleges. She died in 1952, and is buried in the Dyke Road cemetery in Brighton.

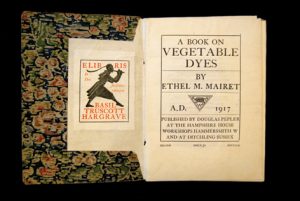

Ethel Mairet, title page to A book on vegetable dyes, 1917, with due dilligence and kind permission of Ditchling Museum

Ethel Mairet’s achievements can be seen not only in terms of her weaving and dyeing techniques, but also in terms of her ethnographic observations, her educational interests and her contributions to the meaning and value of ‘craft’ in the first half of the twentieth century. In many ways Mairet was a pioneer, and a figure of considerable influence. Her work documenting Ceylonese weaving, dyeing and embroidery techniques with Ananda Coomaraswamy was noted by Gandhi, who visited her in 1914: Gandhi was aware of how traditional methods could be harnessed for symbolic and economic impact in colonial India. Yet Mairet herself was a complex and contradictory figure, who has been viewed as part of the ‘intellectual colonialism’ of the West at the same time as sympathising with Indian nationalism.

Described variously as an artists’ colony and a craft community, Ditchling attracted a group of artists and craftspeople whose work was underpinned by an interest in the idea of a living tradition. For some, including Mairet, this involved an interest in communicating her techniques and beliefs about her craft to others, so that they would be developed and continually rejuvenated. Her own work in developing vegetable dyes and emphasising the aesthetic value of plain weaves and the texture of yarns evolved and changed with influences from Europe and the limited resources of wartime. In her educational work at the Brighton School of Art and elsewhere, she was reputed to be an enthusiastic and inspiring teacher.