Professor David Nash has led a team taking the first glimpse inside one of Stonehenge’s giant sarsen stones, providing new insights into these iconic objects.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE, an international team led by Professor Nash – Professor of Physical Geography in the School of Applied Sciences – were able to reveal the geological structure of the stone that made the sarsen ideal for building a monument made to last.

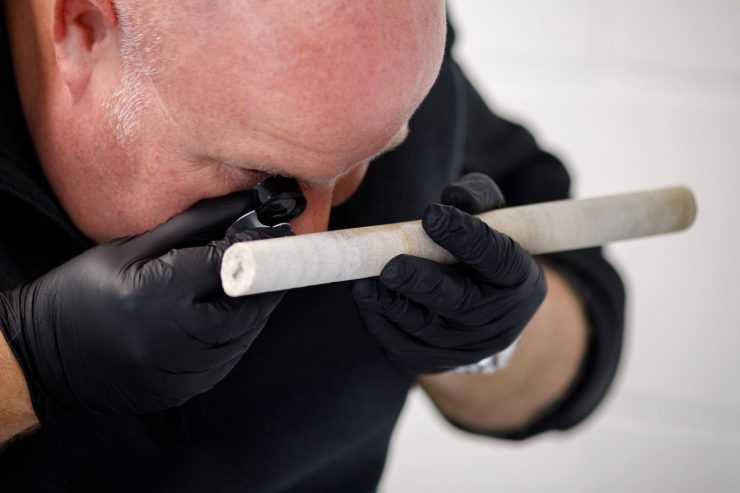

The core sample used to make the first comprehensive scientific analysis of one of Stonehenge’s imposing megaliths has an interesting history itself. It was taken from what is classified as Stone 58 – one of several stones that had fallen over – that underwent conservation work in the 1950s following the discovery of a crack running through the stone. To conserve the stone, three holes around 2.5cm in diameter were drilled through its full thickness (around 1m) to insert metal rods.

Two of the cores then disappeared, though part of one was rediscovered at Salisbury Museum in 2019. The third core was given to Robert Phillips, who worked for the drilling company, and went with him to the USA when he retired. Phillips returned the core to English Heritage in 2018 to provide material for research, before he passed away in 2020.

Analysing a small 7cm section of the 1950s core, Nash’s team found that the sarsen’s structure of sand-sized quartz grains cemented tightly together by an interlocking mosaic of quartz crystals was what made the stone so impervious to crumbling or erosion.

Professor Nash said: “It is extremely rare as a scientist that you get the chance to work on samples of such national and international importance. Stonehenge is part of a World Heritage Site and is subject to the strictest legal protections, so it would be highly unlikely that we would be able to access this type of material today. Getting access to the core drilled from Stone 58 was very much the Holy Grail for our research.

Thanks to help from organisations such as the British Geological Survey and the Natural History Museum we have been able apply a suite of state-of-the-art techniques to the Phillip’s Core. We have CT-scanned the rock, zapped it with X-rays, looked at it under various microscopes and analysed its sedimentology and chemistry. This small sample is probably the most analysed piece of stone other than Moon rock! “

Dr Alex Ball, Head of Division, Imaging and Analysis at the Natural History Museum, said: “We are delighted that our specialist team of scientists from the Museum’s Imaging and Analysis Centre have contributed to reveal further secrets of Stonehenge, showing how our state-of-the-art techniques and equipment continue to unlock new discoveries.”

Typically weighing 20 tonnes and standing up to 7 metres tall, sarsens form all fifteen stones of Stonehenge’s central horseshoe, the uprights and lintels of the outer circle, as well as outlying stones such as the Heel Stone, the Slaughter Stone and the Station Stones. Fifty-two of the original 80 or so sarsens remain at the monument.

The new findings build on further pioneering research published by Professor Nash last year in which he used the so-called Phillip’s Core to show that most of Stonehenge’s large sarsen stones likely came from a site around 15 miles away in West Woods on the edge of the Marlborough Downs. This new geological research provides further data that could help trace the sources of the remaining stones.

The research was an interdisciplinary collaboration between the University of Brighton, Bournemouth University, University College London, University of South Wales, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, British Geological Survey, English Heritage, the Natural History Museum (London), Gatan UK and Vidence Inc. (Canada), and was funded by the British Academy and Leverhulme Trust.

Published by