Images (help us to) communicate

There is evidence of pictures being used to communicate and educate long before language emerged, so their potential for use in the language classroom is evident. What’s more, we live in a multi-modal world where meaning is gleaned from text and image working together.

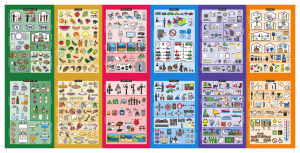

This session made me think of a friend of mine who works in recruitment for the Royal Navy. Part of her job involves running a project with A-level language students where they need to communicate with one another without using English and none of them speak each other’s language. The final product is a pointy-talkie: a picture book with the word for the item in several languages. These have been used in the military since World War II (possibly before but there’s remarkably little to be found on this!) and continue to be used today.

A US military pointy-talkie used in Afghanistan (the photo was issued by the United States Army and is in the public domain. More information available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Defense.gov_photo_essay_090807-A-1211M-006.jpg)

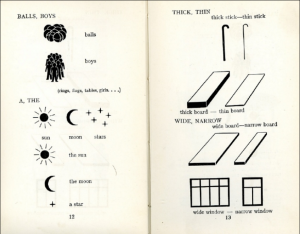

Paul also mentioned the International Picture Language (1939) by Otto Neurath in collaboration with Marie Neurath which I suspect will have been linked with (perhaps inspired) the pointy-talkie.

There are now several versions – in paper, app and even t-shirt form – that help tourists to communicate around the world even when they don’t speak the language.

The meaning of these icons and images in all of the examples above only becomes clear when combined with the text (or other images in the case of the kwikpoint pointy-talkie). Images alone are not necessarily an effective form of communication, but in combination with text, the two can support each other. Since we use a combination of written, spoken and visual cues to help us to communicate and to interpret the world around us, we should do the same in our classrooms.

The importance of visuals is something that has come up in many of our discussions prior to this session, mainly thanks to Jade who is particularly interested in this area and has made me realise that it’s an area that I should consider more. I mentioned that it was one point we had much of our discussion on during the Materials Evaluation task but didn’t go into why at the time so I’ll give a brief summary here.

Part of the process in creating our evaluation framework was to take our list of criteria and prioritise them by choosing our ‘top 10’ non-negotiables. You can see here that under the sub-heading of aesthetics, there’s only one vote for motivating aesthetics. That was Jade. Anything to do with aesthetics hadn’t entered into my, nor Abdullah’s, top 10. Following our lengthy discussion, I realised that it wasn’t that I didn’t think that aesthetics were important, it’s that I’d prioritised other things over them, not realising that even the presentation of the materials – which I do see as being incredibly important (see my post on adapting materials) – should be included in this area. It’s not just about colourful pictures, it’s about mind-maps, tables, giving students sufficient space to write, not over-crowding the page, using relevant images to

- enhance interest and motivation (affective)

- attract and direct attention (attentive) (Duchastel, 1978)

- facilitate learning by showing something difficult to convey in words (didactic/explicative) (Duchastel, 1978)

- help less-able learners (supportive)

- facilitate memory (retentional) (Sless 1981).

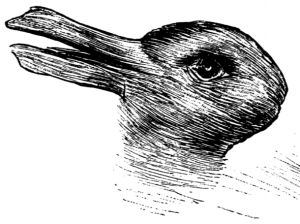

Interpretation: blessing or a curse?

I have of course used images in the classroom – exams are even based on them the IELTS exam, one of our internal language modules is assessed on the student’s description and interpretation of a graph, CAE uses images to prompt students’ speaking, every end of term exam at the Political Studies Institute requires students to write an analysis of a political cartoon… Activities including interpretation or uncoding of an image allow students to employ higher order skills which are required in many areas of our day-to-day lives. (This makes me think of Paul Driver’s Invaders activity – well worth checking out.) But as we saw in class, our interpretations of images are largely based in our own knowledge, experience and beliefs, so these tasks can be very challenging for students. This makes me think of my other love: classical reception theory. I won’t go off on a long and rambling tangent here (even though I’d love to), but reception theory involves analysing what contributes to our understanding of a work (in any medium), what comes from the creator of the work and, perhaps more importantly, the audience and any/all contributors in between (things like our society, beliefs, knowledge and life experience…). The way I interpret an image (or a painting, a play, a film…) will likely be completely different from the way someone with a different background and experience to me will interpret it, and both will be different from how the original work was intended.

This scene of a Roman parade had been/could be interpreted as

- Rome – what it represented at the time: a celebration of victory and/or demonstration of power

- Ancient Rome – what we today see as Rome, what we have been taught about what Rome was and all that we believe Rome represented (imperialism, power, victory, violence, excess…)

- Nazi Germany – the golden age of Ancient World films (post WWII) meant that such scenes were often interpreted as (and sometimes presented as) representations of the hubris of Nazi Germany

- The USA – the second wave of sword and sandal films was released in the early 2000s and seen to be a reflection of/reation to the military action taken by the USA (imperialist tendencies?)

- The EU – Brexit campaigners have recently likened the EU to Nazi Germany’s quest to rebuild Rome (thanks for that one Boris Johnson), clearly showing how these layers build up and our perceptions and interpretations can be manipulated by experience and belief. [On an interesting Classics note, BJ is a Greek not a Roman.]

In some situations this flexibility of interpretation could be excellent grounds for a discussion or employing decoding and visual literacy skills, but could equally lead to a difficult situation or to students each understanding something completely different. The point being that an image must be carefully considered if it is to help, not hinder, communication and understanding. The interplay between text and image is what is perhaps most useful to us as teachers.