At the beginning of this blog I was taken aback by how much potential the study of materials design, adaptation and evaluation had for me. I was left with a sense that this module could be much more relevant to my own future than I thought. I have since been struck by how important it is to have a grasp of this topic to develop as a teacher, and to forge a path in ELT instead of becoming a passenger. In the end, this process has produced results that even then I didn’t expect. I feel like I’ve been given the chance to take more control of what I do as a teacher, giving myself more input in how and what my students learn. I’ve become more personally invested in the classes I provide for learners, and better able to shape their learning experience to meet their needs. I’ve also become more informed about my teaching practices, and more capable of evaluating their validity, in the same way as one might evaluate a set of materials. This has made me able to adapt my teaching style more fluidly and appropriately, again, as one might adapt materials. A key theme of this journey has been the far-reaching impact and significance that materials can have, and the effect this module has had on my teaching is no different.

I’ll conclude it by revisiting my initial goals and describing the ways they’ve been addressed, and finally thinking about where I will go from here.

My goals at the beginning of this process

‘Confidence’ was a recurring word in my opening statement. I wanted the confidence to create more complex material from scratch, and the confidence to adapt materials on a ‘macro’ level – most of my goals were based on building confidence in my abilities to experiment and develop in new directions. As with many things, giving it a concerted effort was the first step. I’ve found out about better ways to employ and exploit types of materials which I used in fairly predictable ways before. The key to achieving this really was the confidence to be more adventurous and creative; not only confidence in myself, but confidence in the methods I wanted to try. This came from reading and seminars about approaches, media and techniques which I either didn’t use, or didn’t realise I used. What I was then able to do was apply principles, and evaluate an idea in such a way that I could rely on as aligning with my beliefs about teaching and learning. The combination of becoming more informed about different possibilities, and actually being able to make informed judgements about their application in my context, gave me the ability to experiment more. Once I had become comfortable with taking on and adapting the materials ideas of others, I then felt confident in creating more of my own ideas, and creating more nuanced materials – and it came from the same ability: pre-use, principled evaluation of materials. An understanding of the principles behind materials was the crux of everything which followed – evaluation, adaptation and design – and the basis on which I’ve developed during this module.

This was one of my specific goals at the outset:

-‘I would love to build my confidence in creating more structured material, which could be more closely tailored for specific contexts and the individual needs of students, and less ‘one-size-fits-all’.

I feel I have achieved this, as shown by the materials we created in the later weeks of this module, which were centred on the individual needs of a small group of learners. An appreciation of whether or not material meets particular needs, and evaluations we’ve done, helped me to target material at ‘specific contexts and the individual need of students’, and I’ve found the ability to do this routinely extremely valuable. However, more importantly, I’d like to expand this goal. The flexible, less closely tailored materials produced by other teachers really motivated me to explore this type of materials design; creating something that can be successfully tailored for a wide variety of individual learner needs. This could be closer to a genuine ‘one-size-fits-all’, or at least one-size-fits-many. Our introduction to flexi-materials was hugely significant in the realisation of this possibility, and the power that teacher-writers are given by this format will, I’m sure, be of great use to me as I continue creating and teaching materials.

Here is another:

– It would be incredibly gratifying to take away the ability to analytically, critically design a course over several weeks, and have the awareness and confidence to adapt not just the content, but also the progression and structure of coursebooks provided for the classes I teach.

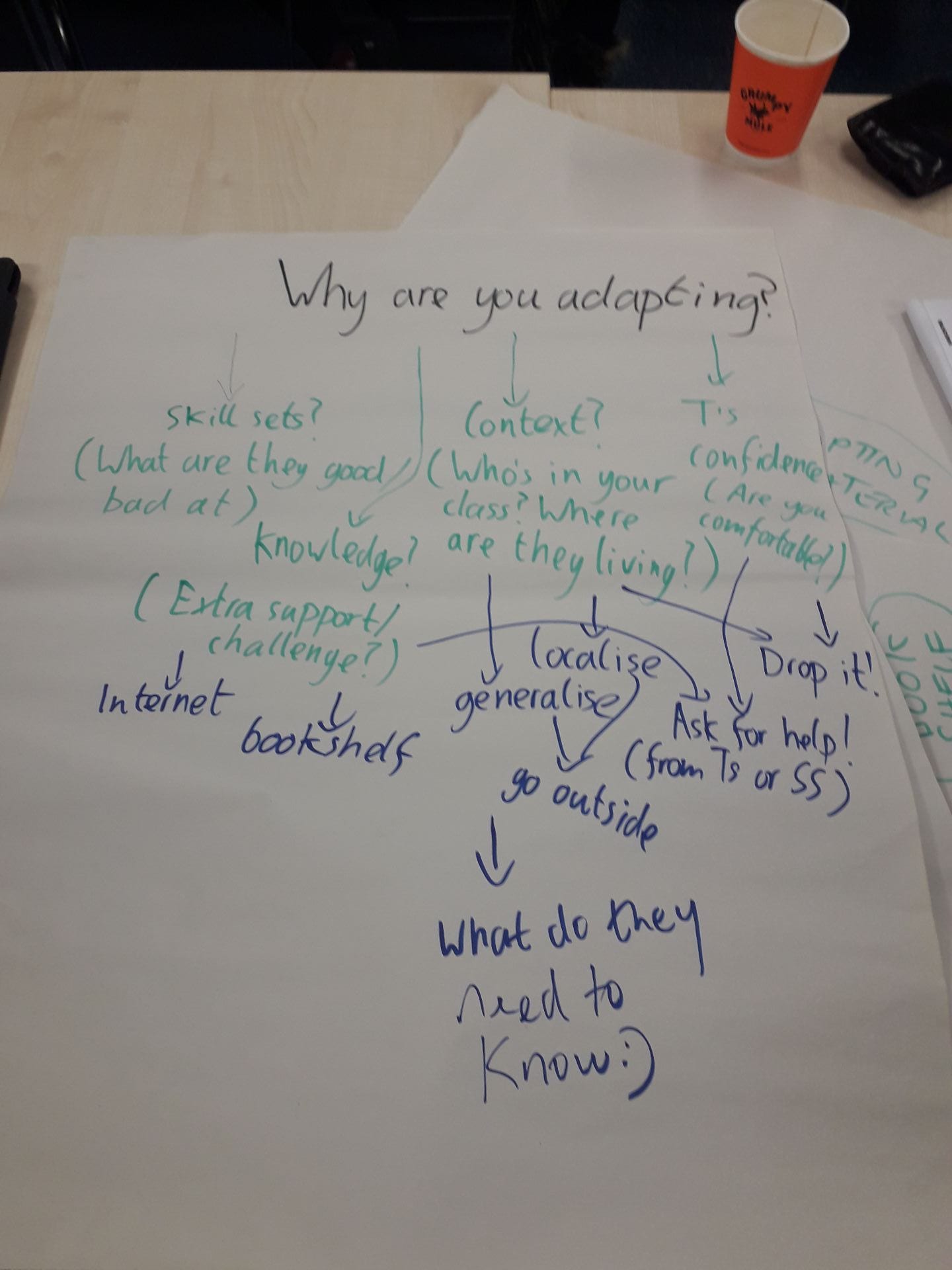

I’ve learned that the cornerstones of any adaptation or creation of materials, whether one activity or a course, are learner needs and personal principles. I believe that the principled evaluation which now underlies any adaptation I make of published materials could support adaptation on any scale. As in the design of materials though, relevant and principled adaptation is based on the needs of the learners. Since this module has begun, I have made more alterations to the way my learners progress through the coursebooks we are obliged to use at my institution. These alterations have been founded in the needs of the learners, and also in my desire to implement particular SLA theories or methodologies. This module has given me the ability to adapt the published materials to fit learner needs, and to better embody the methodologies or language acquisition theories which accord with my principles.

My next steps

In my first post, and throughout this blog, I considered the urgency of the need to adapt to the changes edtech brings to ELT. I was really satisfied to be able to engage more with edtech’s potential during this module, and I was also pleased to be shown that, actually, I was already doing so. Like many teachers, my opinion of the way I engaged with digital materials was inconsistent with how I did in practice. The opportunity to explore their use in multiliteracies and constructivism, as well as through the use of video in language learning, has given me new perspective on their potential. I aim to continue developing in this area as a priority, and to remain motivated to bring the digital world into the classroom, and into language learning. I’m making this a habit now, and will keep exploring new avenues as they appear.

My main aim for the future is to keep being conscientious with my evaluation, adaptation and design of teaching material. Properly founded materials adaptations have enhanced the learning of my students, and improved my planning and in-class use of materials. The value of critically evaluating what you are using, and taking the time to do so, is huge. By using an evaluative process, a set of design principles and your own understanding of learners context and needs, you can create lessons which are as beneficial for them as any material could be. In light of this, I aim to remain committed to these procedures, to try to automatise and build on them.