Following on from my first post, I want to focus on materials in general (not just course books) and how they relate to, and have an impact on teachers and learners.

“Sometimes institutions can be accused of putting coursebooks and equipment before the students”.

McGrath (2013)

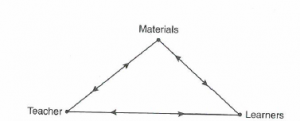

Bolitho (1990) present four visual representations of the relationship between teachers, learners and materials.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

What I interpret from these three diagrams (of four) is that materials are seen as external entities, and they filter downwards into everything else without collaboration and reflection. There is a danger here of the materials being put on an unchallenged and unevaluated pedestal. The reliability and validity of the content, learning principles, and communicative purposes of the materials must be questioned by all stakeholders (similar to what was mention about coursebooks in my previous post). However, this is more easily said than done. Institutions where the culture is for the syllabus and progress measures to be guided by predetermined materials, teachers and the learners may have little say in the content and methods used. In addition, some teachers may doubt their own authority to challenge these pre-packaged materials that contradict their pedagogical principles. It took me several years to feel comfortable with material adaption. This was in part due to the time it took for me to reflect and develop my own teaching beliefs and principles.

Two of the key considerations why materials are seen as a seperate entities is the time and resources it takes to create them. Teachers don’t have or are not given the space to author their own materials. The culture that I am accustomed to is one where the main battle is a juggling act of responsibilities leaving very little space within the working day to create localised materials. In this kind of climate the coursebook or pre-packaged materials can be viewed as the most economical resource for hard-pressed teachers. Yet this implies, to me, that published materials keep teachers and institutions bound to them and asks them to relinquish their control over input and pedagogy in their classroom. The Internet has provided alternatives to the coursebook and there are more multi-modal options available. However, it still means that the materials (whether they are professional or not) are created ‘off-site’ away from the context and needs of individual classrooms.

What are the roles of the teachers and the learners with regard to materials? McGrath (2013) suggests that it can be separated into choice, control and creativity. Technology has done a great service to enable more choice. This is not a global resolution, but it is becoming more and more common that people have access to the Internet. The wealth of materials found online have been created by professionals, researchers, practicing teachers and most wonderfully students themselves. The mobile phone is seen, by some, as the pariah in the classroom while others see it as the answer to all material conundrums. A device that has images, sounds, video (in the case of smart phones), recording capabilities, and research facilities and using its primary purpose, a tool for communication (text or phone calls). The power to create materials is not only in the hands of the teacher, more interestingly it affords the students the use of all its functions as a means of creating their own materials. This view is perhaps a biased perspective, as I strongly believe that mobile phone technology has unequalled educational affordances.

The development of materials should always be reflected upon as an evolving process, where the choices are controlled by the particular learning situations needs. With needs at the centre the materials, teacher and learner all have input. This is, in some respects, represented in Bolithio’s fourth image.

The teacher should be the one in control or managing what is presented and used in class. That is not to say that student input and materials would not be a welcomed, and a more engaging experience for all involved. Post-evaluative judgements would give a better indications of the outcomes of materials (Action Research). The cyclical nature of figure 4 implies that the reflection and evaluation will involve all stakeholders. This should should mean that the materials evolve more in proportion to the localised context.

The ability to create and adapt materials comes with time, reflection and trial and error. Eventually, a ‘bank’ of materials can be accrued while teachers’ adaptive skills become more intuitive. Those materials should present and promote the teacher’s principles and the needs of the students within their context. This has been true for myself, I have moved away from the more behaviourist style of teaching using Present, Practice, Produce (P.P.P) method. The methods and materials I used were mainly materials-as-language, where the students practise and discover individual language items. However, over time it has become clear that I have a preference for a constructivist and sociocultural perspective approach to ELT. This uses task based learning and project work (materials-as-content) as the main focus and language is acquired through the process of doing the activity. It is not fair or helpful to try and polarise materials. The need is what comes first and the appropriate material is selected from there. I would not reject a material simply because it does align itself with my beliefs if it is what is required for the student(s).

During our first week of the Materials Design course (TLM25) we were asked to write on the whiteboard what we wished to learn, improve and understand about materials. Among the very good ideas of my peers, the statements that I wrote were:

• Create

• Evaluate

• Recycle

• Humanise

• Localise

These five phrases sum up what I have been discussing throughout this post. Firstly, I need to understand the relationship between myself, the students and the materials. Despite technology allowing for a more economical means of creating and editing materials, adapting and supplementation skills are still an integral element of this course. What has become clear (if it wasn’t before) is the needs of the students that are the central consideration of materials and their design. Materials are not what make a good teacher nor a good lesson. It is an evolving process of evaluation and reflection that aids the development of a teacher, thus, creating stronger relationships with students and more contextually and pedagogically appropriate materials.

References

Bolitho,R. 1990 ‘An eternal Triangle? Roles for teacher, learners and teaching materials in a communicative approach’. In S. Anivan (ed.) Language Teaching Methodology for the nineties (pp22-30). Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Centre.

Ewer, J. & Boys, O. (1981) The EST textbook situation – an enquiry, The ESp Journal 1.2: 87-105.

Mcgrath, I. (2002) Materials evaluation and design for language teaching, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Mcgrath, I. (2013) Teaching materials and the roles of EFL/ESL teachers: theory versus practice, London, Continuum.

Meddings, L. & Thornbury,S. 2011. Teaching Unplugged: Dogme in English Language Teaching. London: DELTA Publishing

Tomlinson, B. (2011) Materials development in language teaching, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.