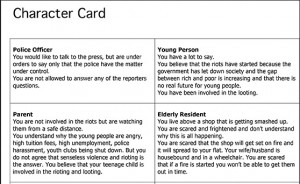

“Mass media and other key institutions ‘contribute to the development and maintenance of hegemonic domination […] They ‘connect’ the centres of power with dispersed publics: they mediate the public discourse between elites and the governed. Thus, they become, pivotally, the site and terrain on which the making and shaping of consent is exercised and to some degree contested”

(Hall, 1975:142 in Hansen, 2010:45-46)

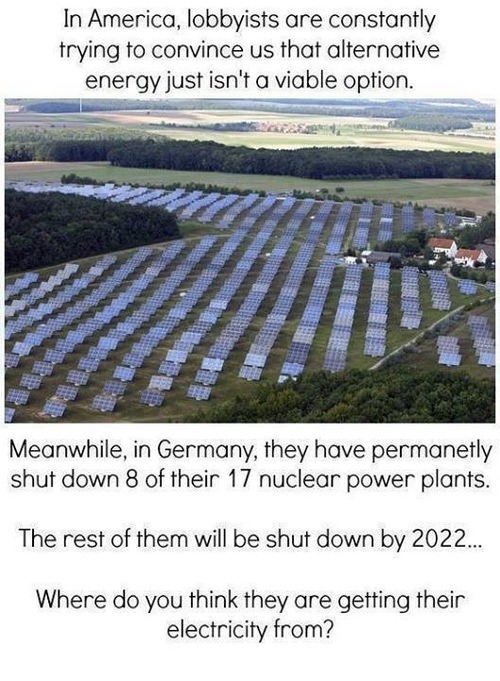

Image: Greenpeace USA

In media coverage of the environment, depending on whose voices and claims makers are used impacts upon how the news coverage is constructed, a representation of the issue, which is crafted within a cultural, economic and political discourse. Recognition of geo-political issues and ‘cultural proximity’ are key in determining what gets covered in the media and for how long (Galting and Rogers 1965).

“The real battle is over whose interpretation, whose framing or reality gets to the floor”

(Ryan 1991:53 in Hansen 2011:38).

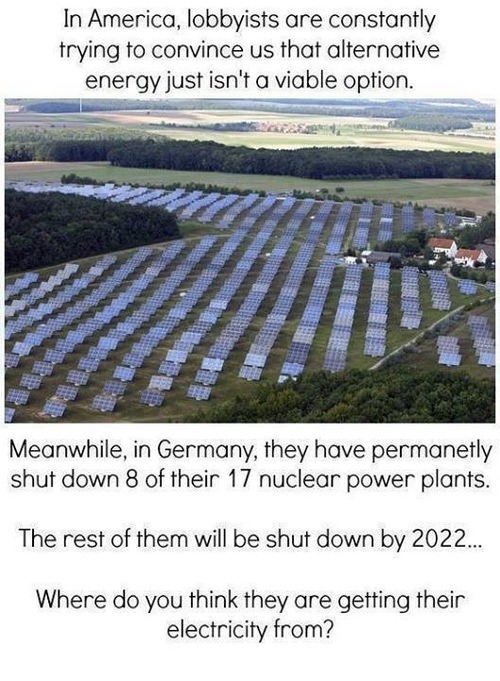

Claims makers command attention, claim legitimacy and invoke action to get to the floor (Solesbury, 1976). Once holding this media space the ‘framing’, the angle and perspective from which the ‘issue’ will be unpacked begins. Firstly, the selection, whose voices are included and why, and secondly the presentation and evaluation of arguments – what information is omitted or decontextualised (Hansen, 2010:39).

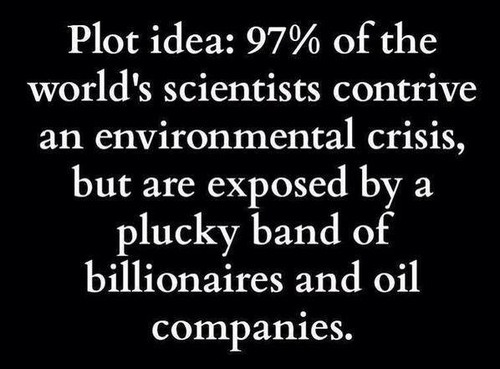

Image: Occupy London

“Framing essentially involves selection and salience. To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation for the item described”

(Hansen, 2010:39).

Image: Greenpeace USA

The overarching issue of news construction of the environment is that regardless of the (il)legitimacy or (un)reliability of the source or claims maker, their inclusion in the content authorises their claims.

The cultural values we associate with journalism and news media, objectivity and impartiality governed by an ethical code, does not take into consideration the limiting practices and cultures of news production; time-pressures, limited sources, hierarchical and editorial hierarchies ad control, or that environmental issues coverage is nearly always events driven, immediate and visual. If environmental issues do not fall into these capacities for framing, and many do not (e.g global warming) how can these complex issues be sufficiently reported upon in terms the wider public can understand and relate to their everyday?

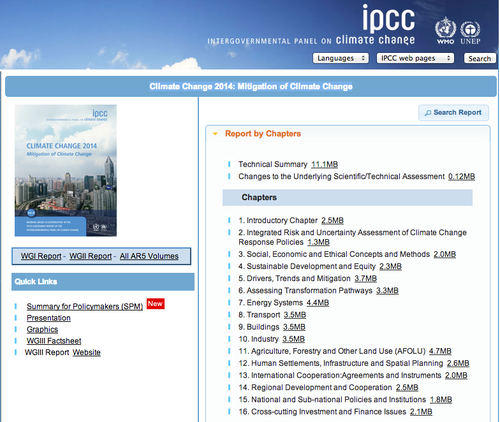

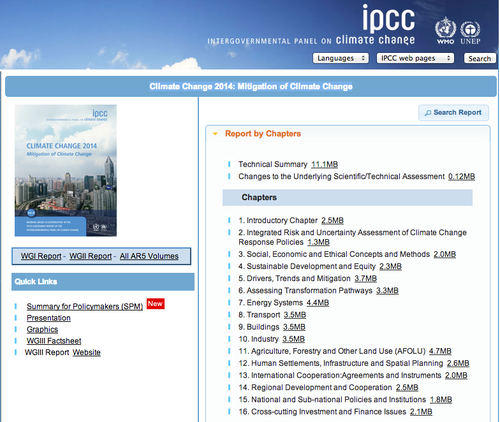

For example, the most recent IPCC (2014) report is not accessible to the public in terms of understanding the wider implications and effects of climate change upon everyday practices, whilst offering solutions to lead low or carbon neutral lifestyles.

Image: Screenshot IPCC Report 2014

Alternatively, this Greenpeace blog constructively pulls apart the key findings of the IPCC report making it accessible and relatable for the everyday reader:

Image: Screenshot Greenpeace Energy Desk

The indeterminate and potentially life-long nature of human-induced and natural environmental disasters “bears no resemblance to the scientific discovery, material existence (scientific, economic, social indicators), persistence or resolution of environmental problems” (Hansen, 2010:38). Such environmental issues and dangers obviously occur regardless of media coverage, though arguably unfortunately many only gain legitimacy and attention once in the news media and are easily forgotten when out of the news domain, further distancing us from such issues and dissolving our recognition of importance. Here we are left with a challenging and worrying quandary, which has arguably led to the avoidance of many environmental issues; the assumption that the environmental is only legitimised by news media attention and secondly, the assumption that if the environmental issue is in the news media the issue is being addressed. This is not always the case. Whose responsibility is it anyway? All of ours?

Bibliography

Hansen, Anders, 2010. ‘Making claims and managing news about the environment’ & ‘The environment as news’. In Environment, Media and Communication. London: Routledge.

Hall, S. 1975, In Hansen, 2010. Hansen, Anders, 2010. ‘Making claims and managing news about the environment’ & ‘The environment as news’. In Environment, Media and Communication. London: Routledge.

Greenpeace Energy Desk. 2014. ‘5 Minute Redux Key Findings’ (Available at:http://greenpeaceblogs.org/2014/03/31/5-minute-redux-key-findings-ipcc-report-climate-change-impacts/?utm_source=gpusafb&utm_medium=blog&utm_campaign=climate, Last Accessed 20/5/14).

IPCC, 2014. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ‘Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change’ (Available at: http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/, Last Accessed: 25/5/14).

Lester, Libby, 2010. ‘News and Journalists’ & ‘Sources and Voices’. In Media and Environment: Conflict, Politics and the News. Cambridge: Polity.