Jenna Allsopp, PhD student, describes six months of handling, researching, splicing and digitising archival film.

In 2019, I undertook a 6 month professional development placement at the North East Film Archive, which was funded by Design Star as part of my doctoral training. The aim of the placement was to provide me with an exciting opportunity to experience a completely different, collections-based, environment to an academic, university-based one I am currently situated in as a PhD student. My work on their North East on Film project provided me with invaluable connections with archivists and curators within my chosen field and geographical location, having recently moved back to my hometown of Newcastle-upon-Tyne after 11 years in Brighton.

The North East Film Archive (NEFA), and its sister organisation the Yorkshire Film Archive (YFA), is a charity which aims to preserve and provide access to the moving image heritage of Yorkshire and the North East of England over the last 120 years, much like the south coast’s own regional film archive, Screen Archive South East, held at the University of Brighton. NEFA and YFA cares for the collections housed in both Middlesbrough and York respectively, made up of more than 50,000 titles which provide a rich and engaging record of time. The majority of films are non-fiction or industrial records, made by both amateurs and professionals. Subject matter includes industry such as shipbuilding, mining, steel and textiles, as well as everyday life such as family parties, school trips, holidays and regional events and traditions. They also hold the Yorkshire and Tyne Tees Television news and regional programmes, alongside a wealth of output from local cine clubs, which reflect a fascinating social history over the last century.

Fig.1: Lining up film and sound reels on a Steenbeck flatbed editing suite at the North East Film Archive, Middlesbrough. Photograph by the author. July 2019

During the placement I was trained in more physical aspects of film handling, such as loading the Steenbeck flatbed editing suite (see Fig.1) with 35mm picture and sound film, which I was shown how to sync accurately. The dark film is the picture and the brown film is the sound.

In 1928 Kodak introduced their Kodacolor process which was widely used by amateur filmmakers until the introduction of the much-improved Kodachrome process in 1935. This process underwent a lot of fine-tuning, particularly in the US where the technology was pioneered, which inevitably had a bias towards the capturing of white skin tones. The inherent racism of early colour photography has been widely written about, specifically the Kodak-issued ‘Shirley’ cards which were used as a standard gauge to calibrate colour in photography and film processing quality control. Named after the first model who posed for these cards, Shirley Page, all subsequent models became known as Shirleys; a Caucasian woman usually against a grey background. This image, as visible on the screen of the Steenbeck in Fig.1, was considered the norm for skin tone and was the desired outcome for processing.

Fig.2: Splicing film cells at the North East Film Archive, Middlesbrough. Photograph by the author. July 2019.

Other physical handling training including learning how to ‘splice’ film cells. Often, and particularly with very old film, the cells can break during viewing on the Steenbeck, so it is necessary to glue them back together. This is done by trimming the break to the nearest frame at each end, connecting them on the splicer shown in Fig.2 and joining the cells with a specialised clear tape. Splicing is also carried out if multiple films need to be loaded onto a single reel for storage.

During my placement we were donated a can of multiple reels of nitrate film which the archive is not allowed to store for more than 24 hours due to its flammability. This particular collection was in terrible condition, so sadly could not be viewed before it was shipped to the BFI whose vaults are insured to hold it.

Fig.3: Examining a donation of cellulose nitrate film at the North East Film Archive, Middlesbrough. Photograph by the author. July 2019.

Cellulose nitrate was first used for photographic roll film in 1889 and was used for 35mm motion picture film until the 1950s. Cellulose nitrate is highly flammable, prone to spontaneous combustion and decomposes with age. The decomposition produces a swirling psychedelic effect as a result of the chemical emulsion drying up and peeling away from the nitrate strip. In the present day, these imperfections of decay have inspired the work of contemporary artists such as Bill Morrison who has used decaying nitrate film as a key medium in his practice.

Fig.4: Audience at the ‘Durham on Film’ screening at the Gala Cinema, Durham. Photograph by the author. July 2019.

One of the main ways members of the public have access to the films in the archives is through public screening events. These are held regularly across the North East and Yorkshire and include films specially selected which feature the area in which the screening is held.

Fig.4 is a photograph I took of the 400-capacity sold out show at the Durham Gala cinema in July. My main duty at the archive was to research the social history for contextual publication alongside the films on the website, some of which were read out to the audience in between films at the screenings. It was very meaningful to read the feedback forms after the events and hear how much the local residents enjoyed the additional context to enrich the films and how many memories these films recalled. Some residents even spotted themselves or old friends in the films!

Fig.5: Cleaning the John Scorer collection in preparation for cataloguing and digitisation at the North East Film Archive, Middlesbrough. Photograph by the author. July 2019.

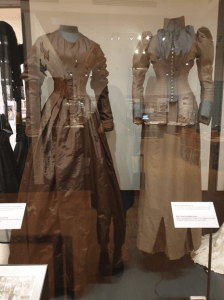

The most rewarding and enjoyable part of my placement was having the opportunity to work on my own donation project. I was handed a box of film that had not yet been viewed, which I watched on the hand winder for the first time. I was given the responsibility to decide if the films were of interest to the North East on Film project and, if so, I cleaned the film (as shown in Fig.5), loaded it onto an archive reel, created a catalogue record, passed the film to the technician for digitisation then researched the social context for publication on the website once the film was live. This project allowed me to experience every aspect of the donation process from acceptance, accession, selection, digitisation to publication.

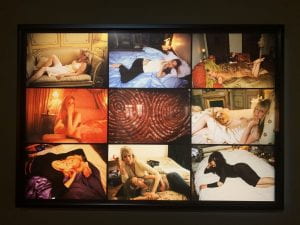

For anyone interested in this collection, it was all by an amateur filmmaker named John Scorer from Cullercoats on the North East coast, who was a middle school teacher and avid collector and maker of historical costume. All five of his films I selected for digitisation can be viewed here.

In total I contributed 30,000 words for the archive in writing, either in formal ‘in-house’ style text for contextual information for films for the NEFA website, or via an informal 3-part blog post, Part One of which can be read here.