BA Fashion and Dress History graduate Emma Kelly reviews an exhibition at The Little Museum of Dublin

Back in September 2017, following an insightful lecture on the life and career of Carmel Snow, Editor and Chief of Harpers Bazaar at The Little Museum of Dublin, it was announced the museum would host a fashion exhibition in the new year. The exhibition: Ireland’s Fashion Radicals, continuing the museum’s focus on objects telling the story of Dublin, would be dedicated to Irish fashion and the radicals of the industry during the twentieth century.

The exhibition opened in January 2018 and I had no idea what to expect. How would the topic of fashion radicals be tackled? Would it be designer-focused or wearer-focused? Would the stereotypical Aran-knit jumper make an appearance? It definitely didn’t disappoint. Curated by historian Robert O’Byrne, it focused on the careers and creations of Irish fashion designers of the 50s, 60s and 70s: Sybil Connolly, Irene Gilbert, Ib Jorgensen, Clodagh, Michelina Stacpoole, Mary O’Donnell and Neillí Mulcahy. In Ireland these decades were defined by social and political turmoil. Yet several designers initiated their careers, striking out into the Irish fashion industry, seeking to make names for themselves.

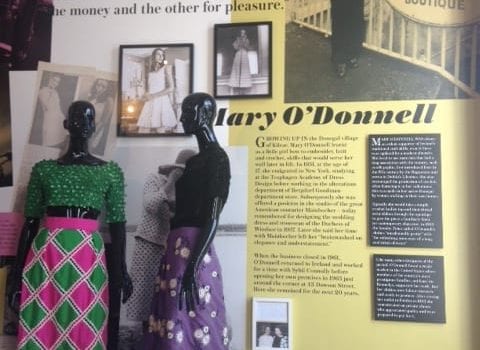

The exhibition wasn’t laid out in the traditional way of mannequins behind glass, organised into rows, with text panels located under or beside the displays. Spread out across two small adjoining rooms, the exhibition was laid out in a more approachable way (Fig. 1), making use of the limited space. Each designer had dedicated wall space, with text and images including photos of the designers, promotional material and sketches. Examples of their work were on mannequins close by, such as the case of Mary O’Donnell (Fig. 2). You could walk right up to the garments.

Walking round the room I was fascinated by the use of Irish textiles. It really added to the celebratory tone of the exhibition as not only was it celebrating Irish talent, many of whom have been largely forgotten, but the use of Irish textiles. Irish textiles are often discussed in relation to industries such as lace, linen and wool. The examples on show were more contemporary in style, examples of the adaption of Irish textiles for a new, international audience. For me they were emblematic of the Irish fashion industry moving forward, taking influence from international fashion but supporting industries in Ireland, without an Aran knit jumper in sight.

One of my personal highlights was a green pleated linen Sybil Connolly gown circa 1960’s. It was the piece I kept coming back to (Fig 3). Emblematic of Connolly’s work, it was romantic and feminine, created with Irish textiles. Pleated linen was her trademark, used time and time again in her designs. The Costume Institute at the Met Museum houses several pieces by Connolly, many of which are of pleated linen. To see such a piece up close was phenomenal. Another Connolly highlight was a promotional photo, reminiscent of the works of Richard Avedon, who took fashion photography out of the studio and into the streets, showing fashion in action. Far from the streets of Paris Connolly’s model found herself in Ireland on a typically cloudy day. I can only imagine what the reaction of passers-by would have been to such a glamorous (bare-shouldered) figure.

I love finding, through exhibitions, that there is more to a familiar object than meets the eye. In this one it was a photo by Cecil Beaton that took pride of place on the wall beside the works of Irene Gilbert. The image, printed onto the wall, is one of his most famous “Fashion is Indestructible” from Vogue 1941 showing a couture model amongst the ruins of a building (Fig. 4). Her outfit was by Irish born designer Digby Morton, born in Dublin in 1906. I wasn’t ever aware of the Irish connection the photo had. The text also mentioned another designer, John Cavanagh, born in 1914 in Mayo and worked with Balmain and Molyneux before setting up his own label. The inclusion of Morton and Cavanagh, as well more recent designers such as Simone Rocha, shows the other side of the Irish industry, those who left Ireland to establish careers in other countries. Emigration is an integral part of the Irish story and it was very fitting that such designers be included alongside Irish born designers who set up their labels in Ireland as well as designers who made their homes and livelihoods in Ireland.

Amongst the designer-wear on show was one ensemble with incredible provenance. The red woollen suit (Fig. 5) was made by Anne, Countess of Rosse née Messel. The unassuming suit has links to Ireland as well to my University town of Brighton. Many of Anne and her family’s garments are housed at Brighton Museum. You couldn’t study Fashion and Dress History at Brighton and not know of the Messels and their long and illustrious love affair with fashion and the crème de la crème of the industry over the decades. The inclusion of the suit was an interesting choice: an ensemble created by a woman who wore garments by some of the designers on show, including Gilbert and Jorgensen. Only steps away was the Irene Gilbert gown Anne Messel wore to Buckingham Palace.

It was amazing to walk round the space and see Irish fashion on show; fashion that wasn’t stereotypical, fashion that could stand amongst the fashion of the world’s fashion capitals, and yet still tipped its cap to Ireland and its culture, from the use of its textiles to the motifs of its culture. The radicals on show in the room were radicals in their own way. In the early years of the new state (from 1922), they forged careers in uncertain times. They took the road less travelled, creating fashion for their Ireland and countries around the world, creations that worked to celebrate the textiles and crafts we have.

Though the exhibition was small, at the end I felt reinvigorated to push on in my choice to focus on Irish dress history. For me, the garments in the room stood as testament to the fact that we did have a fashion industry and that we do have a story in tell.

A version of this post first appeared on the Costume Society‘s website in August 2018.