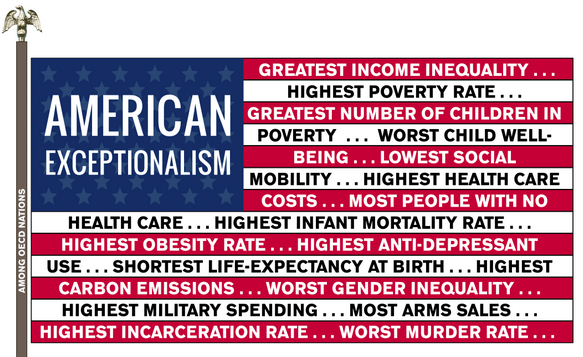

“The city is its people” (Hill, in Hemment & Townsend, 2013, p.88). But without the engagement of the people, citizens are in danger of becoming simply consumers of technology implemented by governments and corporations – building on and consolidating existing power structures following a neo-liberal ideology.

In 2007 the world’s population changed from rural to urban; the majority of people are now living in cities and this is a trend that is set to continue (Elliot, A. & Urry, J. 2010, p138). Alongside this are the extraordinary developments in technology – unimaginable a few decades ago – and the majority of the world’s citizens live not just in a city, but a digital city. While this growing urban population raises issues of sustainability, it could be that the solution is just waiting to be discovered within these digital cities.

In the concluding chapter of Mobile Lives most of the possible outcomes for the future of the city are bleak, however, a more optimistic outlook develops around smart technology, using sensors and monitoring (although this raises privacy questions) to facilitate low-carbon, sustainable lifestyles. (Elliot, A & Urry, J 2010, Pg 147-48).

And 3D printing, while at first seeming only to allow for the creation of more stuff, actually offers the opportunity for greater sustainability – there is a reason why designers and manufacturers are sharing the same anxieties as the entertainment industry a decade ago. Hacktivist Raul Krauthausen’s 3D printing of a wheelchair access ramp is an example of social production – using Creative Commons Licensing to share files.

When presented with such bleakly different futures from the world we live in now, there is a danger of becoming weighed-down with pessimism and not appreciate the amazing opportunities our digital cities offer us now. We don’t know what the future holds and maybe initiatives such as iSPEX, which allow individuals to monitor their own personal and individual damage to the atmosphere, or playful, interactive games such as Play the City that changes the familiar cityscape to one of active exploring, discovery and learning will allow us to create a future we’ve not even imagined.

References

Elliot, A & Urry, J. (2010) Mobile Lives, pp138. Routledge.

Hemment, D. & Townsend, A. (2013). Smart Citizens: FutureEverything [online] Available at: http://futureeverything.org/publications/smart-citizens [Accessed 14 May 2016].

iSPEX (2012). Measure Aerosols With Your Smartphone. Available at: http://ispex.nl/en/ispex/ [Accessed 14 May 2016].

Krauthausen, R. (2013). Available at: http://raul.de/inspiring/printing-a-mini-wheelchair-ramp-yourself-with-a-3d-printer/?lang=en / [Accessed 14 May 2016].

Play the City (2016) Available at: www.playthecity.it [Accessed: 14 May 2016].

Unicef. (2012). An Urban World. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/sowc2012/urbanmap/?lan=en [accessed 1 May 2016].